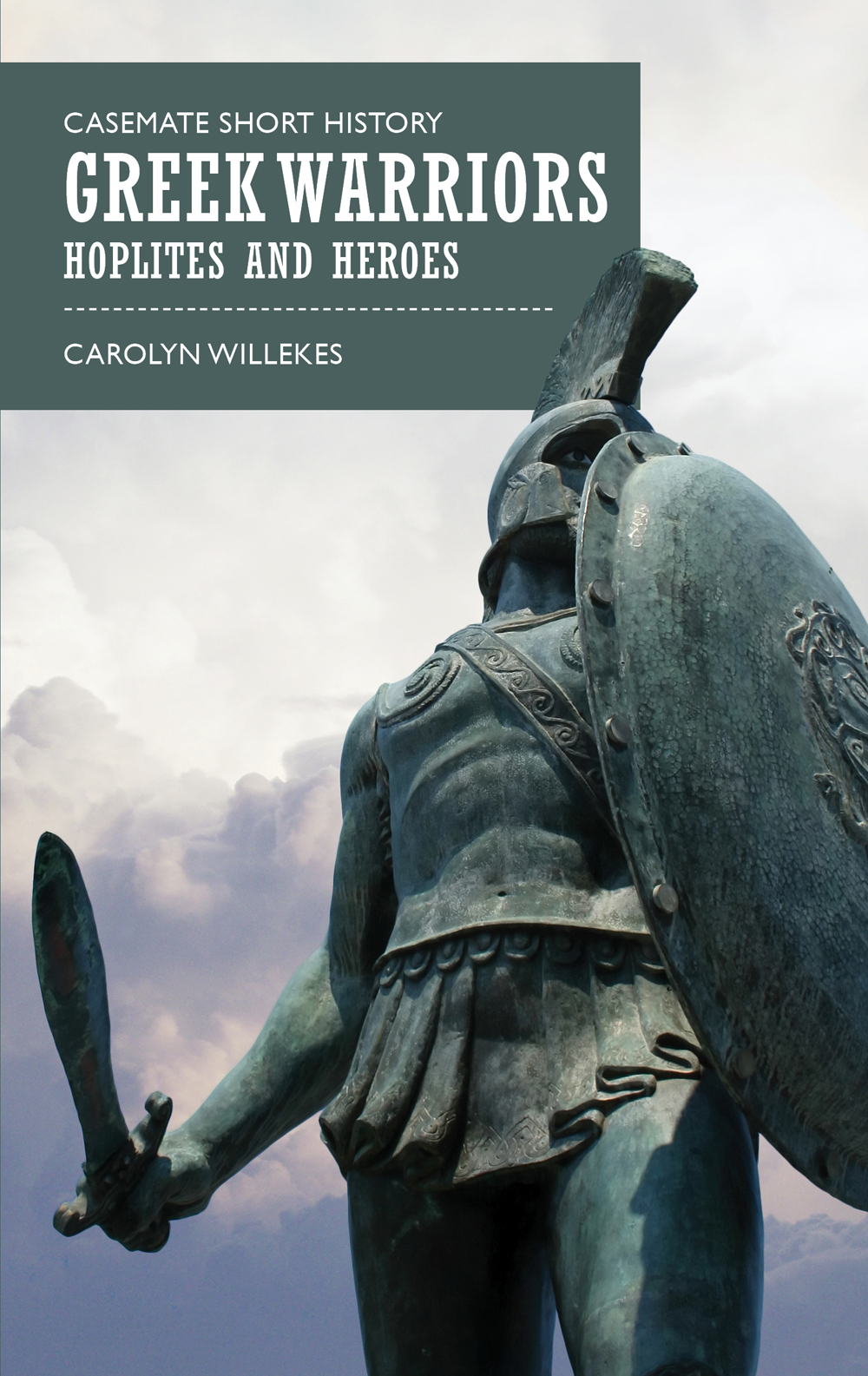

Willekes - Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes

Here you can read online Willekes - Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Griechenland (Altertum, year: 2017, publisher: Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Published in Great Britain and

the United States of America in 2017 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

Casemate Publishers 2017

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-515-7

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-516-4 (epub)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed in the Czech Republic by FINIDR, s.r.o.

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

I T IS IMPOSSIBLE TO TALK ABOUT the Greek warrior without first understanding the land he came from. The role and development of warfare in the Greek world was very much dictated by the environment. The climate is one of hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, but the weather can be unexpectedly violent, with wind and rain systems wreaking havoc on the land. Greece is defined by mountains and islands and has no navigable rivers. The numerous mountain chains criss-cross the mainland and split it into different regions, like Attica, Argos, Boeotia, Lacedaemonia, Thessaly, Macedonia, Arcadia, etc. In addition to mainland Greece there are hundreds of islands, with Crete and Euboea being the largest. Travel between the islands was possible during the summer months, but for the rest of the year the Mediterranean becomes an unpredictable and tempestuous sea. This combination of mountains and islands created a degree of isolation, which in turn led to the development of unique and individual territories. In other words, although the inhabitants of the Greek world all spoke the same language (though with different dialects), used the same alphabet, and worshipped the same gods, they were never actually a unified country under a single centralized government. Instead, each region created its own legal codes, political system, and military, and this is central to our understanding of Greek warfare and how it worked. Rather than uniting under a common entity acting on behalf of greater Greece, each state acted in their own self-interest. The inhabitants of the ancient Greek world rarely saw themselves as Hellenes, only in times of crisis, like during the Persian Wars, did any sense of national identity appear; and even then not every state joined in. Instead, individuals viewed themselves as citizens of the state they lived in: they were Athenian, Spartan, Argive, Theban, not Greek. This absence of unity was the biggest influence on Greek warfare, as each state had no qualms about fighting its neighbour for personal gain. It also led to a never-ending series of shifting alliances, a particularly influential factor during the Peloponnesian War. The concept of Panhellenism (all Greek) did exist in the ancient world. The Olympics were one of the Panhellenic games, only open to Greek citizens; and the term was a favourite of orators, politicians, and generals: both Philip II and Alexander the Great pitched their invasion of Persia as a Panhellenic crusade. It was a handy term, but far from an actual reality.

Compounding the isolation created by topography was the lack of arable land. Greece is not a particularly fertile region, and open plains are difficult to find. This lack of farmland placed a lot of pressure on the state, particularly when populations began to grow during the Archaic period. This led to a period of intense colonization as states sent out groups of citizens to establish colonies. Although the colonies spread across Southern Europe, North Africa, and the coastal Near East, the two most extensively colonized regions were Southern Italy and Sicily a region known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) and the Black Sea. These colonies developed their own governments and acted as independent entities, but they maintained ties to their mother city, which they could call upon in times of stress or danger. Sparta, as we shall see, did things differently. Rather than colonising they only founded one major colony: Tarentum in southern Italy they conquered, invading their neighbours to directly add to their own territory. The ramifications of this are discussed later in this chapter.

Warfare in the ancient world was not static, but perpetually changing and evolving. These changes were direct reflections of shifts in socio-political conditions. The kingdoms of the Bronze Age world fielded aristocratic warriors with their war chariots and an emphasis on single combat. The warriors of the Bronze Age are intertwined with the heroes of myth, men like Achilles, Odysseus, Ajax, Theseus, and Hercules. Our knowledge of Bronze Age fighting techniques is hazy, as our main source is Homer, who recounts part of the siege at Troy in his Iliad . This is problematic as Homer wrote the Iliad several hundred years after the fall of Troy; moreover, he was writing down a story that had been part of an oral tradition for centuries. Thus, we often stumble across passages that seem to describe the style of fighting used in Homers own day, rather than that of the Bronze Age Mycenaean world. The collapse of these kingdoms led to a period in Greek History known as the Dark Ages, during which the inhabitants of the Greek world became more inward looking. This all changed with the start of Archaic Greece, Homers own period, which was defined by the rise of the city state and extensive colonization. The Greek warrior as we know him is a product of this period. He was not a soldier of Greece, but of his state. Some regions were renowned for producing a certain type of warrior or excelling at a particular style of fighting: Sparta for hoplites, Thessaly for cavalry, Athens for its navy. The men who made up these armed forces were citizens of their state, and as such, that is where their loyalties lay. This book focuses on these citizen armies and their role in shaping the course of Greek history. We will look at three formative periods: the Persian Wars, the Peloponnesian War, the rise of Macedon under Philip II and his son, Alexander the Great, and his subsequent conquest of Asia.

When we think of Greek warfare there is one warrior that comes to mind above all others: the hoplite. These men of bronze were the heavy infantry of antiquity, who marched to battle in their disciplined and densely packed formations known as a phalanx. Equipped with a large round shield, spear and sword, wearing a crested helmet and body armour, the hoplite was the iconic Greek warrior. They were the heart of the Archaic and Classical armies. These men were citizen soldiers who fought for their state. The hoplite as we know him first appears in the Archaic period, at a time of great change in the Greek world with the birth of the city-state (the polis ) and a new citizen identity within them. New forms of government and civic structure naturally led to a re-thinking of the army and how to fight a war. No longer did top honours go to the aristocratic warrior, riding to battle in his chariot and fighting in single combat against his equals for his personal honour and prestige. Now it was the citizen group fighting together as a cohesive unit who won glory, not for the individual, but for the state. The armament of the hoplite was as iconic as the man himself. His primary weapon was the dory , a spear measuring 22.5m in length, tipped at each end with a bronze or iron spearhead and butt spike. This weapon could be used both for the offensive and defensive, thrusting over the shields on the attack, or firmly planted in the ground against a charge.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes»

Look at similar books to Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Greek Warriors: Hoplites and Heroes and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.