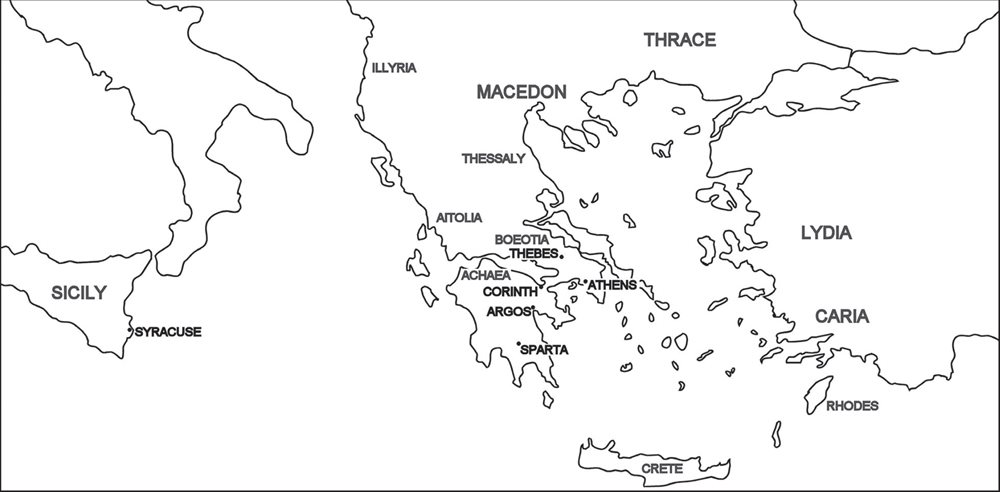

General map.

Major battles. Shaded areas indicate high or mountainous land.

Introduction

T he Macedonian phalanx, the heavy infantry formation devised by Philip II of Macedon and used by his son Alexander the Great to conquer the Persian Empire, was itself a refinement of an earlier Greek formation, with roots already dating back several centuries at the time of Philips invention. The Greek phalanx (it has traditionally been argued) developed after the obscure period when Greece emerged from the Dark Ages that followed the end of the Mycenaean era, was active throughout the Archaic age and reached its most refined form in the period, the great flowering of Greek culture that occurred after the Persian Wars (the failed attempt by the Persians to incorporate the Greek homelands into their empire, an attempt foiled in large part, it is usually understood, by the Greeks phalanx tactics). The men who fought in the phalanx were called hoplites ( hoplitai ), literally armed men or men-at-arms, and were the heavy infantry of ancient Greece, the backbone of all Greek armies.

The Archaic era of Greek history is devoid of any written historical accounts. There are poems chiefly those of Homer, the Iliad and Odyssey , written down probably in the Archaic period but with their origins, as an oral tradition, perhaps dating back centuries before then, perhaps all the way back to whatever historical conflict, near the end of the Mycenaean period around the twelfth century BC , may have inspired the legends of the Trojan War. The extent to which Homers poems reflect actual military practice at any period, whether of the Mycenaean past or the Archaic time of their written composition, remains controversial, and will form part of the subject of the first chapter of this book. It is also unknown whether Homer was a single historical figure or a representative of a wider oral tradition, but for convenience I will here assume he was a real man and composer of the Iliad and Odyssey . Other written evidence is limited to a few fragments of poetry, chiefly the works of Tyrtaeus, a Spartan poet (or one who worked in Sparta) of the seventh century BC (all dates hereafter are BC unless otherwise stated), who composed poems extolling the martial virtues of the Spartans and the joys of dying in battle for the fatherland. Among these fragments are traces of the type of fighting prevalent at the time the extent to which these provide evidence for phalanx warfare will also be considered in the first chapter.

Aside from these sources, we are entirely dependent for Archaic evidence on art and archaeology. For the latter, the Greek practice of making shields and armour from bronze (although this was well into the Iron Age, iron was generally reserved for weapons, with bronze continuing in use for defensive equipment), and of either burying such arms in high-status graves or, later, dedicating captured spoils in religious sanctuaries (especially Delphi and Olympia), means that we have a fair sampling of such equipment in a reasonable state of repair (iron corrodes more rapidly than bronze, and of course organic materials wood, leather, linen are usually lost completely). For artistic evidence, there is a tremendously rich source in the Greek practice of producing painted vases; at first these were adorned with abstract geometric forms, but increasingly it became the fashion to depict human figures in various scenes of everyday life, often military, or in depictions of legendary scenes, often involving combat. The latter provide plentiful visual evidence for arms and armour, as well as some intriguing hints about formations and tactics, as we will see.

The Archaic period transitioned to the Classical with the Persian Wars, at the start of the fifth century, and here too we have a transformation in the quality and availability of literary evidence. The Persian Wars, and the Persian Empire against which they were fought, were the subject of the first ever writer of continuous literary history (at least, the first whose works have survived), the Histories of Herodotus, often dubbed the father of history. Herodotus wrote in the mid-to-late fifth century, at a time when eyewitnesses to the events he was describing were still alive and whose accounts no doubt form the basis of his work, as Herodotus was a believer in autopsy, of seeing for oneself, and travelled and interviewed widely through the Eastern Mediterranean world of his day. He also liked a colourful tale, and declared that his duty was to set down what he heard but not necessarily to believe it, and he was not without some political bias (inevitable in the politically divided fifth-century Greek world), resulting in some calling him the father of lies. Despite the criticisms, and despite the fact that Herodotus did not take much interest in technical military matters and took for granted (as all Greek historians did) a certain level of familiarity with the subject among his readers, there are many valuable clues in his writings as to the nature of infantry combat at the time.

More valuable still was the work of another late fifth-century author, Thucydides. An Athenian general exiled for a botched operation early in the Peloponnesian War (the great war, or series of wars, fought in the late fifth century for dominance in Greece between the two major powers, Athens and Sparta, and their respective allies), Thucydides set himself to write a complete, sober and detailed account of the war, and naturally his History contains a vast amount of valuable material on military matters, along with tantalizing glimpses of the formations and tactics that he assumed were familiar to his readers. Thucydides had his limitations and biases, as do all historians, yet his work is one of the finest pieces of history writing from the whole of antiquity, for its breadth, careful use and evaluation of evidence, and thoughtful judgement. Thucydides died leaving his work (and the war it described) uncompleted, but his history of the war, and of the events that followed, was continued by another soldier-turned-historian, Xenophon.