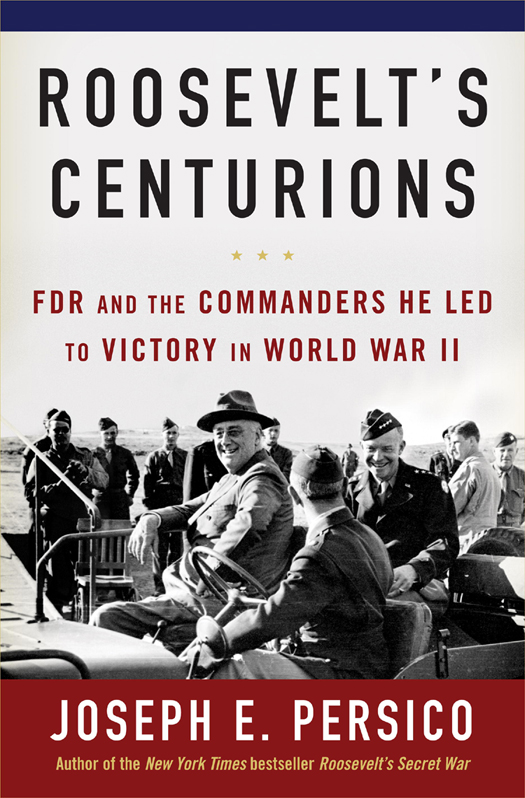

Copyright 2013 by Joseph E. Persico

Maps copyright 2013 by David Lindroth, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Persico, Joseph E.

Roosevelts centurions : FDR and the commanders he led to victory in World War II / Joseph E. Persico.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64543-6

1. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 18821945Military leadership. 2. GeneralsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. AdmiralsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. World War, 19391945United States. 5. World War, 19391945Campaigns. 6. World War, 19391945Diplomatic history. I. Title.

E806.P467 2012

973.917092dc23

2011048698

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: Joe Montgomery

Jacket photograph: FDR Library

v3.1

Preface

W ARS ARE DIFFERENT NOW, BUT THE HUMAN FACTORS AND FORCES at the highest levels change little. The story of Franklin Roosevelt and his top military command sheds light on the perennial issues that confront America when we are challenged. How should we fight our foes? Where and when? At what price? Who decides the wisest course when the best minds disagree? Who should be our allies? And what do we fight for?

FDR answered the final question in his last testament. On Wednesday, April 11, 1945, the day before he died, Franklin Roosevelt was at work on a Jefferson Day speech: Today we are part of the vast Allied forcea force composed of flesh and blood and steel and spiritwhich is today destroying the makers of war, the breeders of hate in Europe, and in Asia. But FDR always looked ahead; he was a man of the future, and the world to come was on his mind. Today, science has brought all the different quarters of the globe so close together that it is impossible to isolate them one from another, he wrote, accurately predicting the emergence of the global civilization that has become the reality of the twenty-first century.

The leaders he chose to fight for his ideals seem distant now, either OlympianEisenhower, MacArthur, Pattonor dimmed by timeMarshall, Arnold, King. Yet each of these men held the lives and destinies of young Americans and the course of democracy itself in their hands. Who they were and how they did what they didhow they fought and how they thoughtrepays our attention, for they were at work in the greatest war in the history of man.

And at the centeralways at the center, in command, smiling yet steelywas Franklin Roosevelt. Now seen as a marble man, a demigod, he was in fact all too human, and to understand him as he wasa man, not a mytharms us well to judge his successors as they struggle with issues of war and peace and power.

Had he lived another day, he would have told America: Today we are faced with the preeminent fact that, if civilization is to survive, we must cultivate the science of human relationshipsthe ability of all peoples, of all kinds, to live together and work together, in the same world, at peace.

That is the world that the commander in chief and his centurions fought for. Their story is told here.

Contents

Introduction

O N M ARCH 4, 1933, F RANKLIN D ELANO R OOSEVELT STOOD ON THE East Portico of the Capitol behind a massive Great Seal of the United States. Four rows of dignitaries, many arriving in black silk top hats, took their places behind him. His son James had been positioned strategically should the paraplegic president, supported only by leg braces, begin to fall. FDRs hand rested on the Roosevelt familys 1686 Bible as Supreme Court chief justice Charles Evans Hughes swore in the thirty-second president of the United States. Along with the civilian powers and duties of the office that Roosevelt assumed that day, he became, under Article II, Section II of the Constitution, the commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States. Ironically, and admirably in a democracy, this oath usually places a military amateur over the most star-studded generals and admirals in uniform. Roosevelt reveled in the authority. Throughout his life, he had displayed an interest in military matters. As a boy he had indulged dreams of attending the Naval Academy at Annapolis, but his doting mother could not bear the thought of long separations from her only child. As a birthday present, FDR once presented his grandson Curtis Roosevelt with the Navy bible, Janes Fighting Ships. His love of the sea reached its fullest expression when, at age thirty-one, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him assistant secretary of the navy. When the United States entered the First World War in 1917, he pleaded with Wilson to be allowed to resign and get into uniform, but the president turned him down. Nevertheless, against the resistance of his superior, navy secretary Josephus Daniels, FDR managed to wangle a mission to the Western Front in the summer of 1918. While there he wore a vaguely military dress of his own design, khaki pants tucked into leather puttees, a gray knee-length coat, a French army helmet, and a gas mask looped around his neck. Though never under fire, he described in a letter home the aftermath of battle. After slogging through oozing mud and around water-logged shell holes, he wrote of discarded overcoats, rain-stained love letters and many little mounds, some wholly unmarked, some with a rifle stuck bayonet down in the earth with a tag of wood or wrapping paper hung over it and a pencil scrawl of an American name.

Fifteen years later, as president, even as he wrestled with the economic tailspin of the Great Depression, FDR, alarmed by the rise of Nazism, fascism, and Japans imperial ambitions, fought to increase military spending, eventually winning congressional approval for a $4 billion creation of a true two-ocean Navy. In 1938, while the country slipped back into the economic doldrums, the president angled for congressional approval to build 20,000 war planes annually. When in 1940 his Army chief of staff, General George Marshall, lobbied for funds to double the size of an Army that ranked somewhere between those of Portugal and Bulgaria, FDR doubled the request.

On September 1, 1939, a transatlantic phone call from William Bullitt, the U.S. ambassador to France, woke the president from a deep sleep to alert him that Germany had invaded Poland. The second world war in a generation had begun. Soon Roosevelt began to unravel the Neutrality Laws that had tied his hands from aiding the Allies fighting against Hitler. When in late December 1940 an anxious Winston Churchill informed him that Britain, facing imminent invasion, was nearly flat broke and we will no longer be able to pay cash for shipping and supplies, FDR hatched, in the unknowable recesses of his imagination, a scheme for giving Britain fifty overage destroyers which he justified by obtaining in exchange several bases of minimal usefulness. This decidedly unneutral act was followed a year later by Lend-Lease, which allowed America to pour billions in arms and equipment into Britain and the Soviet Union, employing the flimsy rationale that the loaned material would be returned after the war. In July 1941 he imposed an oil embargo on fuel-short Japan, which, it can be argued, contributed to the Japanese decision to attack Pearl Harbor.