Here in America we are waging a great and successful war. It is not alone a war against want and destitution and economic demoralization. It is more than that; it is a war for the survival of democracy.

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT, JUNE 27, 1936

Authors Note

I N MORE THAN TWO DECADES covering politics, Ive had a good look at many of the leaders who shape our world. Sometimes I interview them one-on-one; more frequently, I watch from the crowd, where the vantage is often superior. Once in a while, Im lucky enough to witness what since the early 1980s has been known as a defining moment, when the character or perception of a political figure is crystallized. I was in the theater in Prague in 1989 as Vclav Havel announced that the Czech Communist Party had fallen from power; I rode around in a small bus with Bill Clinton in 1992 and with John McCain in 2000 as each defined himself for a national audience in just a few weeks in New Hampshire; I stood five feet from George W. Bush at a smoldering Ground Zero as he vowed through a bullhorn to retaliate for the attacks of September 11, 2001.

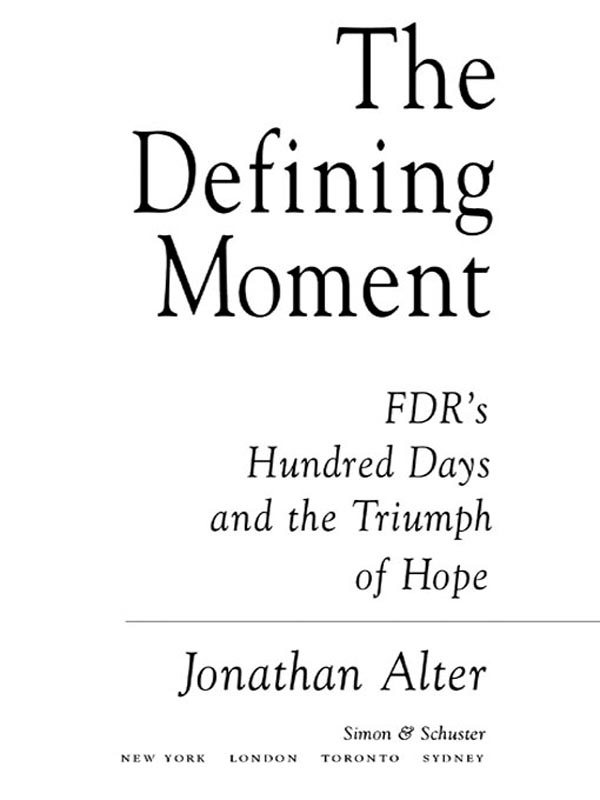

But whenever I think about defining moments, I keep going back to the one that took place a quarter century before my birththe desperate winter of 1933 when Franklin D. Roosevelt narrowly escaped assassination, then restored hope with his fear itself Inaugural Address, his first Fireside Chat, and the thrilling legislative experimentation of what came to be known as the Hundred Days.

This book is not a full account of Roosevelts life or of the early New Deal. Instead, its the story of how at one of the darkest moments in American history, a political and communicative genius saved American democracy. FDRs intelligence was hardly at genius levels; he was lampooned right up until 1933 as a lightweight. So Ive included a biographical opening that examines where he acquired the sense of security that he later conveyed to the world. This section takes him from mamas boy through Washington operator through the trauma of polio. Then I focus much more closely on one pivotal year: from June 1932, when he was nominated for president in Chicago on the fourth ballot, until June 1933, which marked the end of the Hundred Days. The culmination of that momentous period is covered in a final chapter on Social Security and in the Epilogue.

This is a thematic narrativea slice of historythat details how Franklin Roosevelt became president of the United States and revived the spirits of a stricken nation. I try to trace both his manipulative streak and his famously first-class temperament, which helped lift Americans out of their mental depression without curing their economic one. FDRs stunning debut in office was the flowering not just of versatile thinking but of brilliant instincts for leadership. Who influenced him? How did he grow himself into a surpassingly inspirational figure? What grand mixture of timing, cunning, and character gave him and his generation what he later called a rendezvous with destiny?

Roosevelt died in office in 1945 before he could write any memoirs, and his letters in this period are mostly dutiful and unrevealing. He was the first president who did most of his domestic business on the telephone, where, with a few exceptions after 1940, his conversations went unrecorded. So another angle of vision is required. Sometimes my lens is journalistic, as I scan for the revealing anecdote; sometimes it is more historical, a search for deeper connections with the help of archival material from the 193233 period or for the leadership secrets behind FDRs swift turnaround of a failing enterprise. Taking a cue from FDR, who referred to himself at Warm Springs, Georgia, as Old Doc Roosevelt, I also see my role almost as a doctor examining a patient, in this case a man who became the most important president since Abraham Lincoln, and the most underestimated.

FDR was, by many accounts, the most consequential man of the 20th century. Yet it is now nearly 125 years since his birth and more than sixty years since his death. With that in mind, Ive included footnotes with bits of historical context and a few comparisons to recent presidents to help illuminate the main roads of the story. The Notes section identifies sources and provides amplification.

Although the Roosevelt literature is vast, no previous book about FDR has concentrated so closely on his role in the 193233 period. In recent decades, most authors have focused on the later years of his presidency. FDR may be commonly remembered for bringing victory in World War II, but its worth recalling that he did so only with the help of the Allies. The first time he saved democracy, in 1933, he accomplished it more on his own, by convincing the American people that they should not give up on their system of government. Before he confronted fascism abroad, he blunted the potential of both fascism and communism at home.

Instead of viewing the Hundred Days as the opening act of the Roosevelt presidencythe more traditional historical approachI depict it as the climax of an exquisite piece of political theater. This performance was only possible because of a supreme self-confidence in his ability to lead the country when it was, as he later put it, frozen by a fatalistic terror. The story that follows, then, is not just about the early days of the Roosevelt presidency but about where his confidence came from, and how he used it to win power, restore hope, and redefine the bargainthe Dealthe country struck with its own people.

The result was a new notion of social obligation, especially in a crisis. In his second Inaugural, in 1937, FDR took stock of what had changed: We refused to leave the problems of our common welfare to be solved by the winds of chance and the hurricanes of disaster.

We live in an age when the question raised by any work of history is: Why now? Roosevelt is of lasting interest not just because we, too, must face our fears, real and imagined; not just because of a few similarities and many differences between him and another president with a famous name, confronted with big problems. I wrote this book to better understand a few timeless questions about the nature of crisis leadership and the meaning of the American experiment in self-government. What is government for? How can it be mobilized in an emergency to secure safety and ease suffering? Where do hope and inspiration come from, and what might they accomplish?