A T ABOUT 9:30 P.M. ON February 15, 1933, headlights stabbed into the warm Florida night as cars pulled into Miamis Bayfront Park, skirting a dense crowd that had gathered to greet the president-elect. Politicians, publishers, and other civic leaders jostled in the throng, hoping that the next time a flashbulb exploded in the dark, it would catch them in the same shot as the smiling, victorious Franklin D. Roosevelt. His open automobile rolled slowly along, allowing him a chance to catch the eager eyes of cheering spectators. They had crammed themselves onto makeshift benches, each little more than a plank set precariously atop two stools, in the hope of seeing the man soon to move into the White House.

At least one of Roosevelts aides worried about the threat posed by the teeming masses. Raymond Moley was a Columbia University political science professor and an expert in criminal justice, acting as speechwriter and all-purpose consultant to Roosevelt as a member of the group whom journalists liked to call the Brains Trust. Just now, Moley decided his brief was security, and he said to his neighbors, This kind of thing scares me to death. How can the Secret Service possibly protect any man with the crowds pressing in?

Politics outweighed such concerns. Although the campaign had ended, the president-elect still needed to keep in contact with the people. Roosevelts car came to a halt, and he hiked himself up onto the seat back so he could be seen over the heads of reporters and the microphones and cameras they raised aloft to record him. Paralyzed by polio, Roosevelt often made brief appearances from the back seat of an open car, which saved him the pain and effort of walking and standing atop his wasted legs.

Roosevelt took a microphone and held it in his left hand, camera flashes glittering off the two ringsfamily signet and plain bandhe wore on his pinky. He expressed admiration for the city of Miami and, after saying he looked forward to his next visit, returned the microphone. A radio engineer, caught off guard by the brevity of Roosevelts remarks, asked him to repeat them for broadcast, but the president-elect declined, then smiled and waved some more, lowering himself back down into his seat. He had little time: he wanted to catch a northbound train so he could get on with the vital pre-presidential business of choosing his cabinet secretaries.

The flashbulbs made popping noises akin to the sound of a small pistol. Americans tuning their radios to the event heard the announcer describing the scene, listing off the public figures present: Chicago mayor Tony Cermak, Florida newspaper publisher Bob Gore, Miami mayor Redmond Gautier. The broadcaster faltered. For a moment the airwaves carried the inarticulate sounds of commotion in the crowd, a womans screamand a new series of sharp sounds, five or maybe six in all. Someone in the darkness was firing a gun.

Cermak, just a few feet from the president-elect, suddenly lost the ability to stand on his own. A stain began to spread on his shirt, dark rather than red in the dim light. A car door flew open, and someone dragged the wounded Chicago mayor onto the back seat, where the unhurt Roosevelt held Cermaks head in his lap, feeling for a pulse.

The assassin was standing on one of those wobbly benches so he could see over the heads of the crowd, and he managed only two

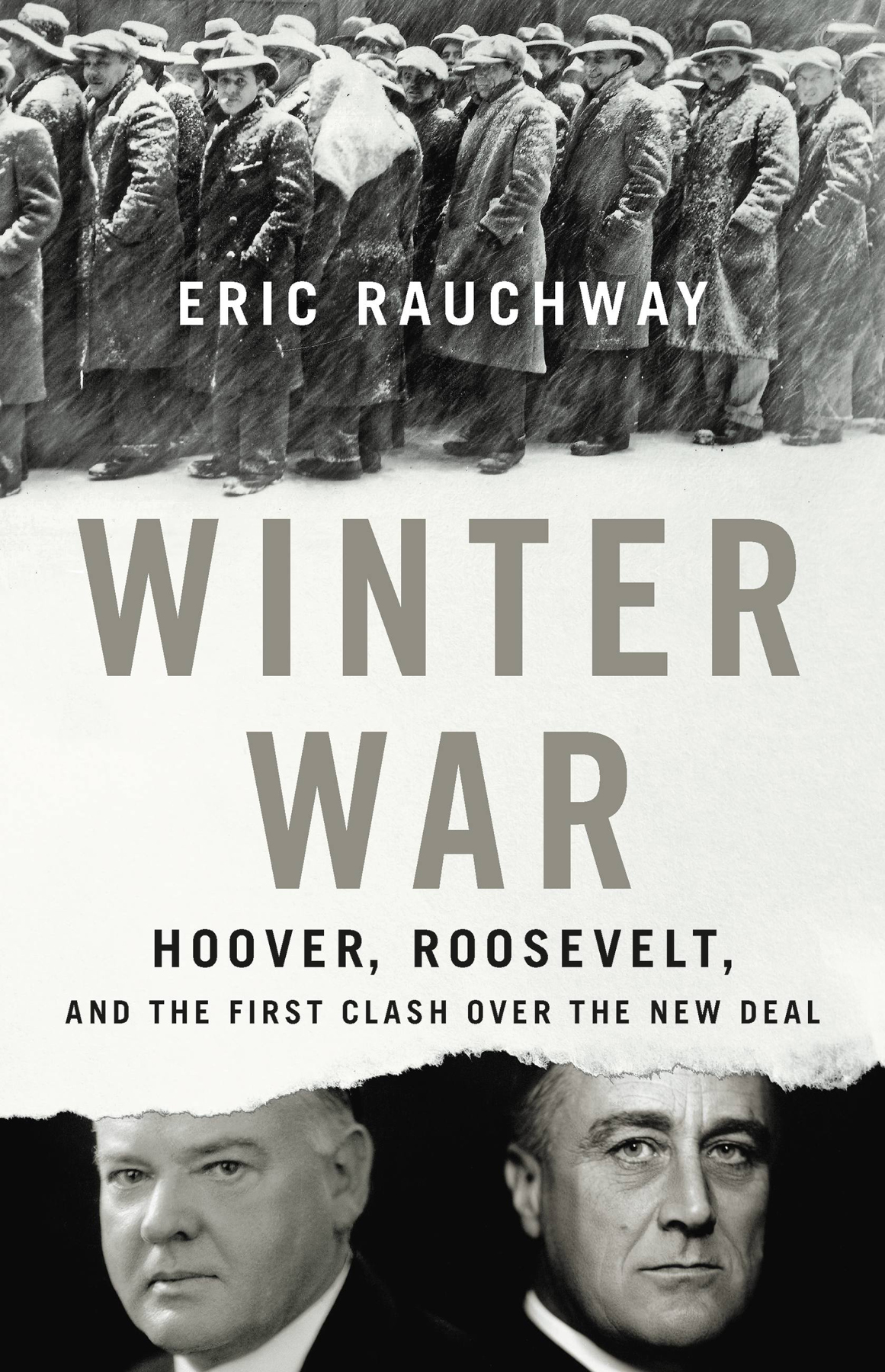

For a few seconds on that evening, the fate of the New Deal depended on the faulty balance of an unhappy man with a gun. Americans various reactions to that close call showed how much they had already invested in Franklin D. Roosevelts promised program of recovery, relief, and reform, for which an overwhelming majority had voted the previous autumn. By the middle of that Great Depression winter, people throughout the world, whether they supported or opposed Roosevelt, knew what to expect of his presidency and had laid plans accordingly. That the assassin missed his mark meant that Roosevelts ambitious proposals to save the United States from Depression and fascism had survived only this most immediate and dramatic threat. The New Deal still needed to surmount the formidable challenges to the president-elects agenda posed by Herbert Hoover, who had two final weeks in the White House, and whose reaction to the near miss was perhaps the most revealing of all.

I F THE SHOOTERS UNCERTAIN FOOTHOLD and the courageous Mrs. Cross were what had saved the president-elect, it remained unclear what had moved the gunman to endanger Roosevelt in the first place. On arrival at the jail, Ray Moley joined the police officers and their prisoner to help with the interrogation. When he was just a boy, thirty-two years before, Moley had been at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo when a disaffected son of immigrants, an unemployed industrial worker named Leon Czolgosz, fatally shot

From questioning, it emerged that the Miami shooter was an Italian immigrant named Giuseppe Zangara, motivated apparently by a strong desire to kill big men, of whom Roosevelt, as president-elect, was now one. Zangara had come to the United States in 1923 and afterward attained citizenship. He was a bricklayer, and a member of the union for his trade and of the Republican Party. And he held politicians and capitalists responsible for the chronic pain he suffered in his stomach.