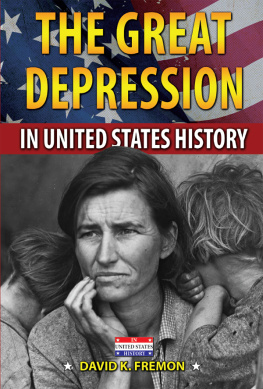

The event that defined the 1930s in the United States occurred sixty-three days before the decade began. On Thursday, October 24, 1929, panicked investors traded the value of stocks on Wall Street down 11 percent. Pandemonium enveloped the Stock Exchange in New York City. Brokers crowded the floor with heavy orders to sell; hysterical spectators mobbed the visitors gallery; and crowds gathered outside in utter disbelief. The market steadied somewhat on Friday and Saturday but dipped again on Monday. By October 29, now known as Black Tuesday, investors had lost more than $30 billion in The Great Crash, bringing the Roaring Twenties to an end.

The ten-year Great Depression that followed was not the product of a single day or week. Wall Street had shown symptoms during preceding months. Nevertheless, it was still a shock to the American people and to President Herbert Hoover. Soon, as banks failed, companies foreclosed on mortgages, unemployment became widespread, and bread lines formed throughout the country, grimly confirming the state of the economy. A reporter for The New Republic magazine, Bruce Bliven, described a common scene in 1931, at the Municipal Lodging House in New York City: There is a line of men, three or sometimes four abreast, a block long, and wedged tightly together so tightly that no passer-by can break through. For this compactness there is a reason: Those at the head of this grey-black human snake will eat tonight; those farther back probably wont.

Similar lines formed daily in almost every U.S. city. Those who did not make it to a shelter slept in doorways, on park benches, or in subways. On October 7, 1932, The New York Times reported the arrest of fifty-four men for idling in a subway. Most of them considered their arrest a stroke of luck because it meant they would have free food and lodging for at least a night. There also were long lines at employment agencies, where dozens of applicants might apply for a single job.

In many cities, only the most destitute families could receive welfare, and the childless or single were not eligible. Some people managed to earn a few cents a day shining shoes or selling apples. President Hoover later said, and possibly believed: Many persons left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples. Still, this saved a few from the humiliation of accepting charity. As Joseph Heffernan wrote of his observations as mayor of Youngstown, Ohio,... I have seen thousands of these defeated, discouraged, hopeless men and women, cringing and fawning as they come to ask for public aid. It is a spectacle of national degeneration.

While American families struggled and suffered, politicians tried to discover how this economic disaster had happened and what needed to be done to improve the economy.

Some believed that Hoover had no plan to counter the effects of the Wall Street crash. They were concerned that he was a do-nothing president who believed the best course was to sit and wait for normal economic forces to bring back prosperity, even though millions might suffer in the meantime. His public statements showed a blind optimism as he continued to tell Americans that the fundamental business of the country... is on a sound and prosperous basis. On March 7, 1930, he assured people that the crisis would be over in another sixty days. Then long after those sixty days had passed and the unemployment figures, even by optimistic estimates, had climbed to 4 or 5 million, he again told them the crisis was over.

Calvin Coolidge, Hoovers predecessor, is associated with six years of American prosperity. As secretary of commerce under both Coolidge and Warren G. Harding, Hoover had pledged in his campaign: Given a chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years... poverty will be banished from this nation. There were a few skeptics, but most Americans optimistically chose him over his opponent, the progressive (and Catholic) Democrat Alfred E. Smith, in the presidential election of 1928. Hoover was conservative, Protestant, Middle Western, and, as he described himself, just a boy from a country village, without inheritance or influential friends.

But Hoover was not naive. Because he believed the psychological state of the country was important to recovery, he was determined to bolster confidence. Soon after the crash, he told his secretary, Ninety percent of our difficulty in depressions is caused by fear. Throughout his presidency, Hoover tried to lessen this fear and cheer up his people. In October 1931, he attended the World Series in Philadelphia, thinking that his presence there would show the nation that he was unconcerned, and there was nothing for the people to worry about.

When the economy didnt improve in spite of all his encouraging statements, Hoover told newsman Raymond Clapper in February 1931: What the country needs is a good big laugh. There seems to be a condition of hysteria. If someone could get off a good joke every ten days, I think our troubles would be over. In 1932, he asked humorist Will Rogers to come up with a joke that would make people stop hoarding. To singer Rudy Vallee, he made a promise: If you can sing a song that will make people forget their troubles and the depression, Ill give you a medal.

But a joke or a song did not comfort those suffering. In September 1932, The New York Times published an item nineteen months after Hoover had observed that the country needed a good laugh, almost a full year after he had attended the World Series to show that all was well. The news story was brief:

DANBURY, CONN., Sept. 6. Found starving under a rude canvas shelter in a patch of woods on Flatboard Ridge, where they had lived for five days on wild berries and apples, a woman and her 16-year-old daughter were fed and clothed today by the police and placed in the city almshouse.

The woman is Mrs. John Moll, 33, and her daughter Helen, of White Plains, N.Y., who have been going from city to city looking for work since July, 1931, when Mrs. Molls husband left her.

When the police found them they were huddled beneath a strip of canvas stretched from a boulder to the ground. Rain was dripping from the improvised shelter, which had no sides.

On Broadway in New York City, the effects of the Depression still showed on the faces of passers-by. Producer and director Herman Shumlin later described the scene to author and radio commentator Studs Terkel for his 1970 book Hard Times: An Oral History of The Great Depression:

Two or three blocks along Times Square, youd see these men, silent, shuffling along in line. Getting this handout of coffee and doughnuts, dealt out from great trucks, Hearsts New York Evening Journal, in large letters, painted on the sides. Shabby clothes, but you could see they had been pretty good clothes.

Their faces, Id stand and watch their faces, and Id see that flat, opaque, expressionless look which spelled, for me, human disaster. On every corner, thered be a man selling apples. Men in the theater, whom Id known, who had responsible positions....

One man I had known lived in New Rochelle. Proud of his nice family, his wife and three children. He had been a treasurer in the theater which housed a play I had managed in 1926....

It was in 1931 that I ran into him on the street. After I had passed him, I realized who it was. I turned and ran after him. He had averted his eyes as he went by me. I grabbed hold of him. There was a deadness in his eyes. He just muttered: Good to see you. He didnt want to talk to me. I followed him and made him come in with me and sit down.

He told me that his wife had kicked him out. His children had had such contempt for him cause he couldnt pay the rent, he just had to leave, to get out of the house. He lived in perpetual shame. This was, to me, the most cruel thing of the Depression. Almost worse than not having food. Accepting the idea that you were just no good. No matter what youd been before.