Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Memories, thank God, cannot be photographed No, to be honest, even if I had all the material in the world in front of me, notes from the First World War, letters, passports, family photographs, love letters and everything that attaches itself to an eventful life like mussels to a ships keel, I still wouldnt have used it as people would expect here Yes, I love the half-light, but please dont confuse the half-light with blurriness and anything washed-out.

George Grosz

And now the Torch and Poppy Red

We wear in honor of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

Well teach the lesson that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.

Moina Michael

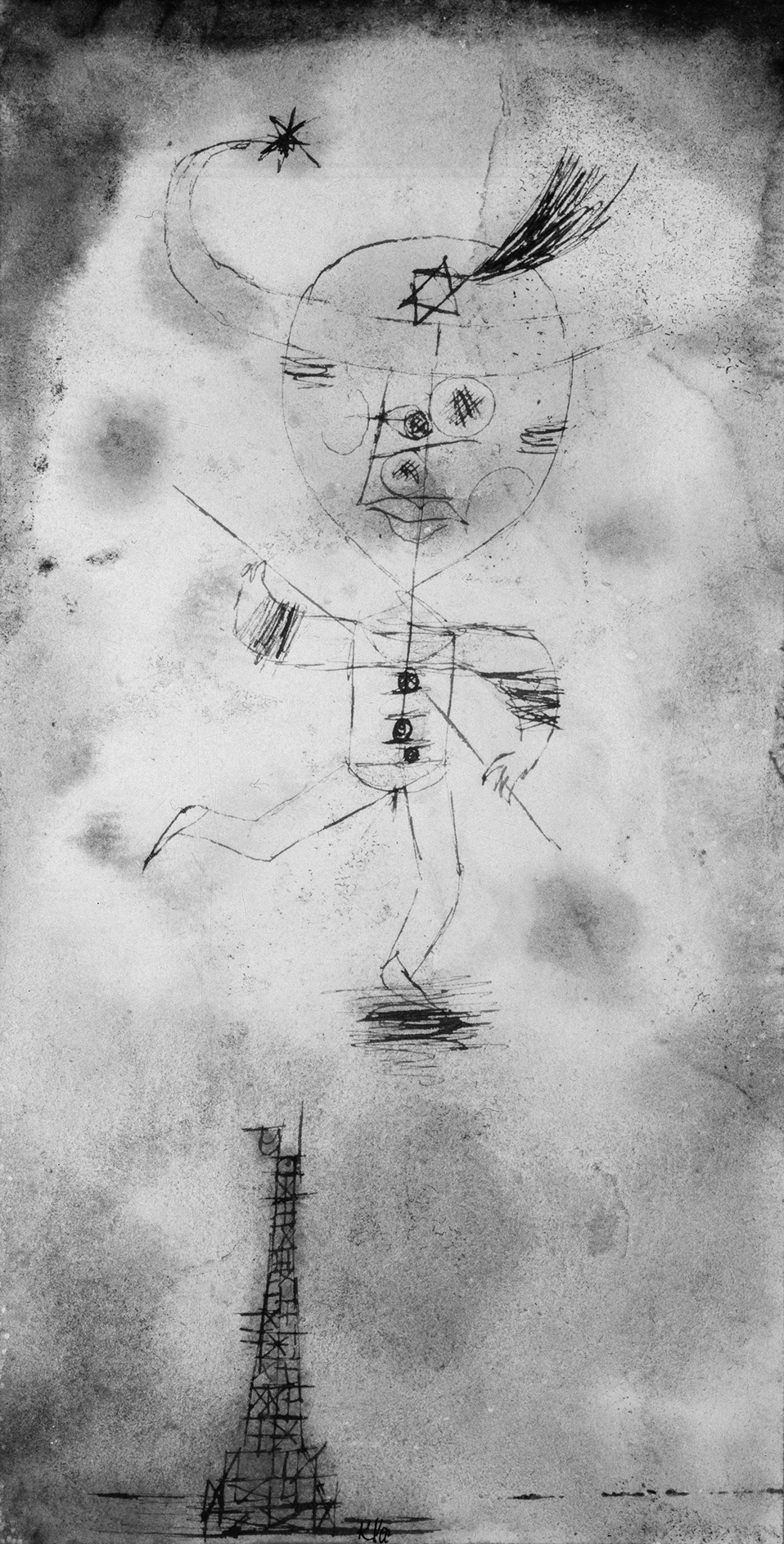

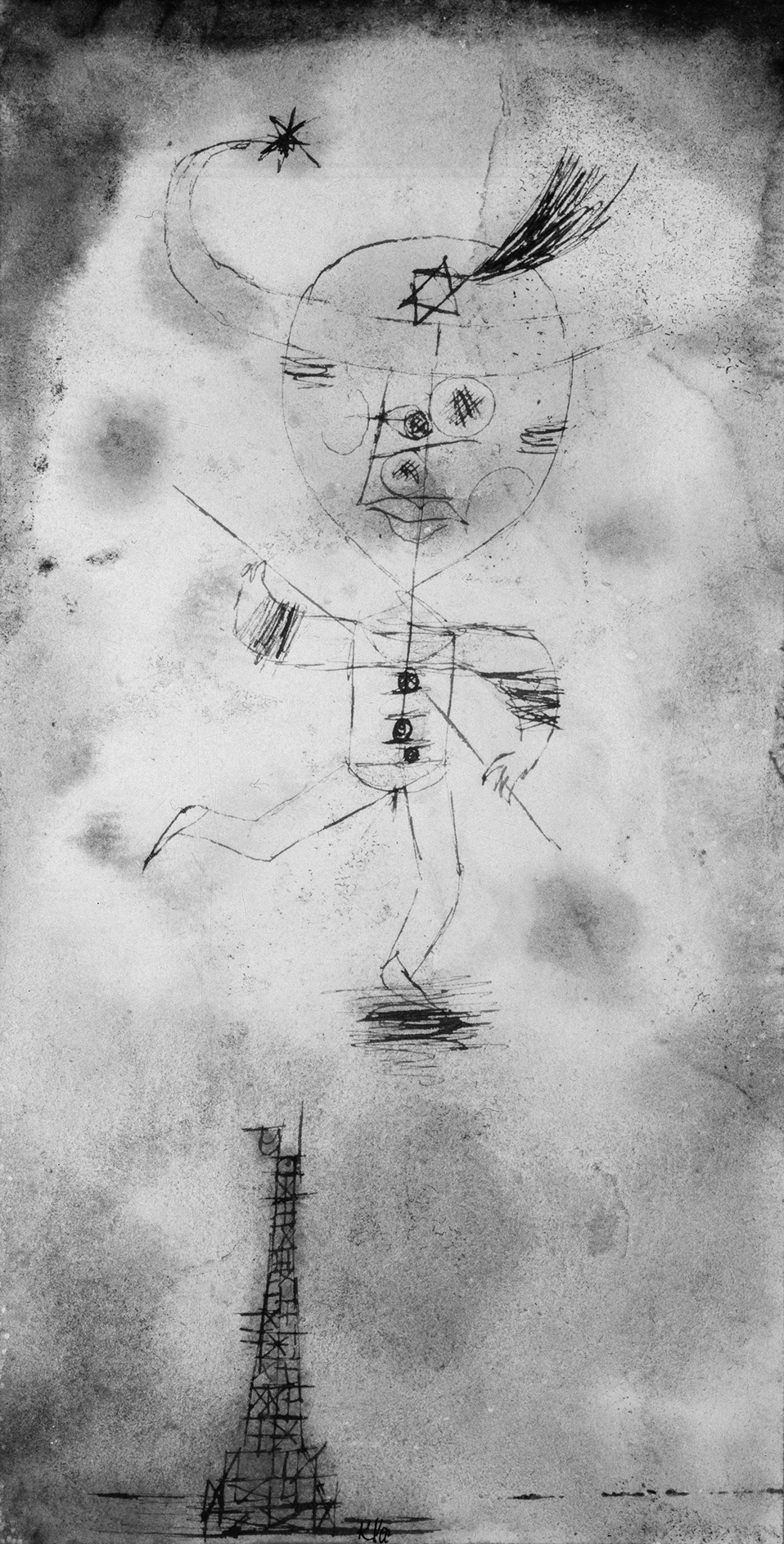

Paul Klee, The Comet of Paris , 1918

I N THE EARLY hours of November 11, 1918, the German Kaiser dangles at the end of a long noose strung between two skyscrapers in New York. Confetti flutters through the sunlight and swirls around the lifeless German monarch. Obviously this isnt Wilhelm II in the flesh but merely his likeness, a larger-than-life cloth puppet complete with moustache and spiked Pickelhaube helmet. Long white paper streamers tossed from the upper stories catch on the point and sway majestically, high above the street.

The armistice between the Allies and the German Empire took effect at 5 a.m. Eastern Standard Time. After four years of relentless fighting, the Germanscalled Huns since the beginning of hostilitieshave been brought to their knees. The Great War has been wonat the cost of more than sixteen million lives worldwide. New Yorkers learn the news from the morning papers and take to the streets by the thousands. A sea of people swells below the skyscrapers, decked out in suits and bowler hats, in their best Sunday attire, in olive drab and nurses uniforms. They walk shoulder to shoulder, arm in arm, saluting, embracing. Church bells peal, salutes are fired, marches and fanfares join with millions of laughing, singing, and chanting voices to form a din like crashing surf. Honking their horns, drivers steer through the crowds at walking speed, while those inside wave flags enthusiastically above the cars. The cheering city erupts in a spontaneous festival with hand-painted posters, self-proclaimed tribunes, musical bands and people dancing with abandon in the streets. All work comes to a standstill on this day of victory, whichso they believewill soon lead to peace throughout the world.

Moina Michael had recently taken a leave of absence from her job as a housemother and instructor at a womens teaching college in Georgia, and for several weeks has been working for the YWCA. In the buildings of Columbia University in Manhattan, this solidly built woman of almost fifty helps young women and men prepare for overseas service. The most capable among them are to cross the Atlantic to become civilian workers behind the front lines, helping soldiers get needed suppliesor so they think. Two days before the end of the war, Michael happens to get hold of a copy of the Ladies Home Journal featuring the war poem In Flanders Fields by Canadian lieutenant John McCrae, which begins with the lines: In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses, row on row. The page in the magazine is ornately decorated with heroic soldier figures hovering, as though ascending to heaven, above a graveyard covered in red poppies. A rapt Michael reads the poem to its conclusion, where McCrae conjures up the image of a dying soldier whose ever-weakening hands pass on the torch of battle to the survivors. The words and images echo inside her, as if the poem were written just for her, as though the voices of the dead were speaking directly to her. She is the one who is meant. She must extend her hand and grasp the sinking torch of peace and liberty. She must become an instrument to keep the faith. She must ensure that the memories of millions of victims never fade. They cant have fought in vain. Their deaths cannot have been senseless.

Michael is so moved by the poem and the mission she suddenly envisions that she takes a pencil and jots down verses of her own on a yellow envelope. The lines center on the poppy. Swearing a vow in rhyme, she pledges to pass on the lesson from the fields of Flanders to future generations: Oh! you who sleep in Flanders Fields, / Sleep sweetto rise anew! / We caught the torch you threw / And holding high, we keep the Faith / With All who died.

While shes writing down these words, a group of young men approach her desk. Theyve collected ten dollars as an expression of thanks for her help in furnishing their YMCA quarters. As she accepts the check, everything comes together. Her thoughts cannot remain mere words, no matter how well rhymed. Her poem must become reality. I shall buy red poppiestwenty-five red poppies, she tells the dumbfounded men. I shall always wear red poppies. She shows them McCraes poem and, after a bit of hesitation, recites her own. The men are enthusiastic. They, too, pledge to wear red poppies, and Michael sets off to procure some. But while the great metropolis has all manner of artificial flowers, its selection of the bright red Papaver rhoeas so lauded in verse proves rather deficient. As a result Moina spends the final hours of the war scouring New York for fake poppies. At last she finds some at Wanamakers, a gigantic New York department store selling everything from notions to automobiles, and boasting a tea room with much crystal on display. There she buys one large poppy for her desk and two dozen four-petaled blossoms, all made of paper. Back at the YMCA, she pins the latter to the lapels of the young men she thinks will soon be fulfilling their duty in France. Such are the humble beginnings of an amazingly successful symbol. Within a few years, poppies will come to stand throughout the English-speaking world for the memories of those killed in the First World War.

The enormous significance of this symbol emerged from an extraordinary moment in history, a time when people around the world were celebrating and reflecting and swearing revenge. The poppies point back to the past and forward to the future all at once. On the one hand they are an admonition to confront the most recent chapter of history and never to forget it. In this sense, they are part of a global culture of commemoration, which will ultimately see ceremonies held, monuments erected, and the names of the fallen chiseled in stone at government buildings and military bases. On the other hand, Moina Michaels idea also looks ahead. For her, the blood that was shed and the masses who sacrificed their lives and health impose a responsibility upon the future. Her nave hope, born of spontaneous inspiration and her own deep religiosity, is that flowers will blossom on the soldiers graves. For her as well as for many of her contemporaries, the end of the war poses the urgent question of how the future will unfold. The armistice conjures visions of a better life, but also unleashes fears. It gives birth to revolutionary ideas, desires, and dreamsbut also to nightmares.

![ZHyul Vern - Off on a Comet [Hector Servadac]](/uploads/posts/book/834994/thumbs/zhyul-vern-off-on-a-comet-hector-servadac.jpg)