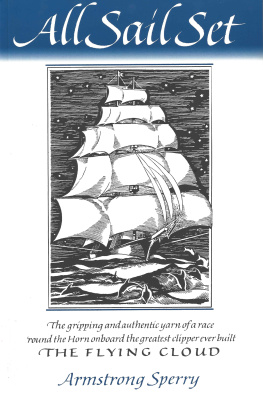

Flying Cloud under sail by N. Currier

Launching of Flying Cloud, April 15, 1851

Donald McKay, builder of Flying Cloud

Donald McKays East Boston shipyard, 1869

Boston Harbor, view from Fort Hill, 1854

Flying Cloud, loading for California

Captain Josiah Perkins Creesy, Jr., master of Flying Cloud

Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury, United States Navy

New York Harbor, looking south from Union Square, 1849

Forest of masts in San Francisco Harbor, 1851

Sextant, 1820, a vital navigational tool

Compass card showing four quadrants

Cape Horn, heavy seas over lee rail

Cape Horn, forecastle deck awash

Cape Horn, mammoth following seas

Cape Horn, shipwreck

As a sailor myself, I admired Eleanor Creesy for her skill in navigating Flying Cloud on her record-breaking voyages from New York to San Francisco. I wanted to know more about what Eleanor faced during that eventful maiden voyage in 1851, what she saw and did as the weeks passed and the vessel sailed on toward Cape Horn. My curiosity led to the writing of this book.

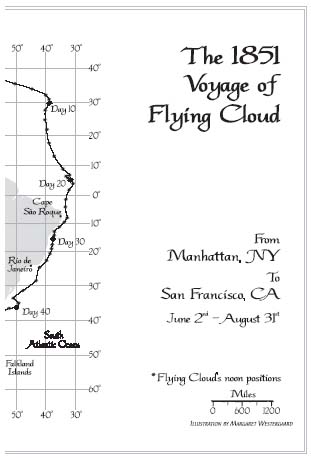

The most important step in understanding Eleanor involved plotting Flying Cloud s daily progress on nautical charts based on the information contained in the ships log. The original handwritten log of Flying Cloud s first voyage from New York to San Francisco is in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Another frequently cited copy appears in Carl C. Cutlers Greyhounds of the Sea . The log entries provide the date, the ships position, the course steered, distance made good, wind directions and approximate velocities broken down into the three parts of a sea day, and remarks concerning important events that transpired over a twenty-four-hour period.

Using this information, I plotted Flying Cloud s daily runs. I noted the course steered in blue pencil versus the course actually made good in black pencil. It was not enough just to mark the ships daily latitude and longitude as asterisks on the chart. I had to know if Eleanors intended course actually corresponded to her true course. Currents, wind, and waves can move a vessel off the intended track. By plotting the course steered in addition to the course made good, I discovered discrepancies that led me to a more refined understanding of what Eleanor faced at various points throughout the voyage. The illustration of the ships course through the doldrums and the influence of an easterly current on the ships track is a good example of this. (See page 114.)

The log provided all I needed to plot the direction of the winds Flying Cloud encountered relative to her course through the water. I drew arrows on the chart to show the wind directions during each part of a nautical day, enabling me to see clearly the angle of the wind in relation to the sails. This was important because certain wind directions are more favorable on a given track than others. Flying Cloud sailed the fastest when the wind blew over the left or right side of the stern. Conversely, if Eleanors course put the wind over either side of the bow, Flying Cloud sailed more slowly. The plots on the chart revealed all the good and bad days from an efficiency and speed standpoint better than words could paint the picture.

The log included terse comments from the captain, many of which proved invaluable when it came down to reconstructing the voyage. In particular, references to the mutinous acts of two of the crew and insubordination of the first officer opened up a glimpse of the tensions aboard the ship. Other more routine entries indicated what sails were set and what sails were not, steps taken in heavy weather, accidents, and other details of vital necessity in my effort to write about the voyage in a realistic manner.

Of key importance as well was the ships position in relation to landmasses, trade wind belts, and ocean currents. All of these factors were foremost in Eleanors mind every day of the journey, and they were in mine as well, as I found myself transported back in time to the deck of the ship, figuratively looking over her shoulder as she went about her duties.

A study of Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maurys sailing directions added further insight into Eleanors duties as navigator. She had his book, Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts , aboard during the voyage, in addition to his charts. Studying a volume of Maurys sailing directions at Princeton University helped me understand Eleanors ability to absorb highly complex subject matter, as did my study of the basics of celestial navigation.

Technical knowledge, however valuable it may have been, amounted to just part of the overall foundation upon which I built the narrative. I needed to know as much as I could about Eleanor and her husband, Josiah Perkins Creesy. In some short accounts of Flying Cloud, Eleanor Creesy is said to have been kind, sensitive, and fond of socializing. She is said to have acted as the ships nurse, to have been benevolent to the crew, and to have helped plan the provisioning for the voyages.

My own research bears this out. According to the Samuel Roads Papers in the archive of the Marblehead Historical Society in Marblehead, Massachusetts, a crewman who served aboard Flying Cloud in a later voyage stated that they were well fed and ate fresh meat twice a week, which was quite unusual on most merchant ships of the day. This is direct evidence that Eleanor saw to it that the men under her husbands command received better than usual treatment, at least in terms of their meals. Also among the primary sources related to Flying Cloud at the Marblehead Historical Society is a letter written by a passenger aboard the vessel during the maiden voyage, Sarah Bowman. She stated that Eleanor was kind, sensitive, social, and fond of art and poetry. Bowman also described her: Such glorious eyes I never saw, large liquid and hazel, soft as a gazelles and always beaming with kindness on someone. The letter also related that Eleanor treasured a blade of grass during the long voyages far from anything green and that on her trips to China she was unafraid of storms.

References in a diary by one of the passengers aboard Flying Cloud during the maiden voyage were also helpful. The diary of Israel Whitney Lyon, I. W. Lyon Papers, at Mills College Library in Oakland, California, indicated that he spent time reading poetry to Eleanor. He noted twice during the voyage that his two sisters, who were traveling with him, were ill, and that another passenger, a Mrs. Gorham, drank poison by mistake. As the ships nurse, Eleanor took care of the passengers. Eleanors duties extended well beyond those associated with navigation.

Birth, marriage, death, and other records from the Marblehead Historical Society provided additional insights into both Eleanor and Josiah Creesy. Records from Arthur Cheever Cressy, of the Creesy family, also assisted me in gaining insights into Josiahs background and family history.

Many of the published sources I consulted in my research referred to Eleanor as Nellie and to Josiah as Perk. I found no primary documents to account for these nicknames. The Creesy letters, archived at Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut, contained a collection of correspondence by Josiah Perkins Creesy and members of his family. In all of these letters Eleanor was referred to as Ellen and Josiah was referred to as Perkins. I have therefore referred to them in the same way in the narrative. (The following letters were used in the text: a letter by Josiah P. Creesy to his brother William, dated March 28, 1851, and an excerpt from a letter by Emily Lord, Williams wife, dated April 13, 1851 [VFM 1559, Manuscripts Collection, G. W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc.].)