CHINA CLIPPER

CHINA CLIPPER

The Age of the Great Flying Boats

ROBERT GANDT

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

Annapolis, Maryland

The latest edition of this work has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

1991 by Robert L. Gandt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Naval Institute Press paperback edition published in 2010.

ISBN: 978-1-61251-424-6 (eBook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

China clipper : the age of the great flying boats / by Robert Gandt.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. SeaplanesHistory. 1. Title.

TL684.2.G36 1991

629.133347dc20

91-15386

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

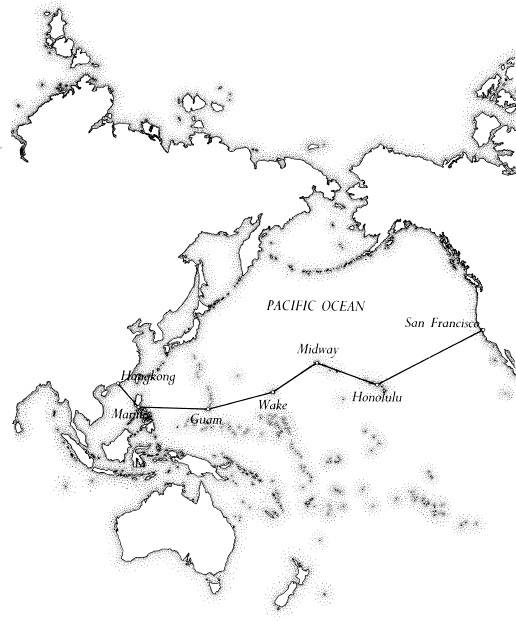

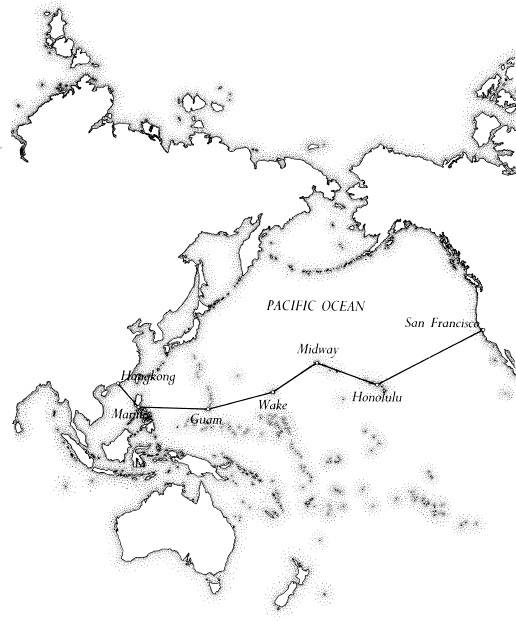

All line drawings by J. P. Wood. Frontispiece map by William Clipson.

To Ruth Gandt with love

Contents

Why the Flying Boat?

By the third decade of powered flight, when aeronautical technology had evolved to the contemplation of over-ocean travel, not one major civil airport yet possessed a long, flat, paved surface sufficient to accommodate the weight of an oceangoing transport airplane. Nor was any airline or sponsoring government inclined to construct such a surface. A more expedient option seemed availablethe two-thirds of the planet that happened to be already flat, unobstructed, and, incidentally, covered with water.

Thus arrived the age of the great flying boats. It lasted sixteen years, commencing with the news of the Dornier Do X project and ending with the postwar scuttling of the Boeing boats. This brief episode occurred at a crossroads in history. It was a time when the ancient rites of the sea were joined, for just a moment, with the infant craft of flight.

From the beginning, its days were numbered. Even the unlikely nameflying boatwas an anachronism. The hybrid craft was regarded just as its name implieda boat that happened to be capable of flight.

It was never a wholly satisfactory scheme. Neither grand pianos nor airplanes belong in sea water, quipped the critics, with justification. For airplanes, the ocean was a place of peril. Salt water ate like acid into metal components. Flotsam and submerged objects ruptured fragile duralumin hulls. Ice floes lurked like mine fields in northern waters. Giant swells turned sheltered harbors into heaving, mountainous seascapes. Boarding docks and motor launches were required to embark and deplane passengers, often in tossing seas.

These harsh realities are often blurred in latterday recountings. Histories of the flying boat, like those of the airship and steam locomotive, tend to conjure up nostalgia. Mystique substitutes for fact. Which aircraft was the most romantic? The most famous? Appeared in the most headlines? Engaged in the most spectacular flights? Carried the most eminent passengers? Which was the fairest of them all?

Aeronautical history ought to interweave with function. As a prerequisite to understanding, we must ask unromantic questions: What was the aircrafts weight? Tare? Wing loading? Power-to-weight? Load-to-tare? Range with a revenue payload? Without? When and where did it fly?

But there is more. The pure fact book disregards the subtle historical nuances of an era. In aviation history, machines are inextricably bound to the lives of the men who construct them, fly them, deploy them, destroy them. The account is punctuated by human pride, greed, courage, soaring ambition, egregious folly. Soulless machines become imbued with the passions of their flesh-and-blood builders.

People thus count for as much as machines. From the record of the great flying boats, we ought to ask: By whom was this airplane built? Why? By whom flown? What was it designed to do? Did it do it well? If not, why not?

Why the flying boat?

The feel and flavor of the flying boat era were eloquently conveyed to me during the past decade by three pioneer captains, Marius Lodeesen, Horace Brock, and William Masland, all now deceased. Further valuable insight was contributed by old boat captains Fran Wallace, Jim ONeal, Harry Beyer, Bob Ford, Al Terwilleger, Thomas Roberts, and Ken Raymond, all veterans of Pan American.

Navigator/instructor E. F. Blackie Blackburn contributed his knowledge of celestial navigation as practiced on the flying boats.

Mr. Sergei Sikorsky kindly reviewed the text concerning his father, Igor Sikorsky, and made available the archives of United Technologies Corporation, which are managed by Ms. Anne Milbrooke.

The considerable resources of Pan American World Airways were indispensable in the research for this book. For this kind assistance I am indebted to Pan Ams Vice Preident for Corporate Communications, Jeff Kriendler, and librarian Li Wa Chiu. Valuable materials were also contributed by the Martin Marietta Corporation, Dornier GmbH, Lufthansa, British Airways, and the Boeing Company.

Old friend and colleague, Captain J. P. Wood, produced the excellent line drawings and the appended graphics.

Of particular assistance with French flying boat data was Stephane Nicolaou of the Muse de lAir et de lEspace at Le Bourget Airport. Materials and advice about the German boats were generously given by historian Fred Gutschow of Munich, Germany. Mr. R. E. G. Davies, Curator of Air Transport at the Smithsonian Institutions National Air and Space Museum, lent frequent help and provided the recently unearthed story of the Martin M-156. A special acknowledgment is owed Dr. R. K. Smith, author and historian, for his forthright critique throughout the production of this work.

CHINA CLIPPER

E d Musick had never wanted to be a hero. It was hard to understand, looking at him, why he had been chosen for the role. He possessed none of Lindberghs youthful charisma. He was a slender, soft-spoken man, neither handsome nor articulate, forty-one years of age. He spoke infrequently, and then with a sparsity of description.