First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Pen and Sword Aviation

An imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Robert Le Page and Jonathan Falla 2011

ISBN 978 1 84884 544 2

eISBN 978 1 84468 600 1

PRC ISBN 978 1 84468 601 8

The right of Jonathan Falla to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound by CPI UK

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen and Sword Aviation, Pen and Sword Maritime, Pen and Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

by

Jonathan Falla

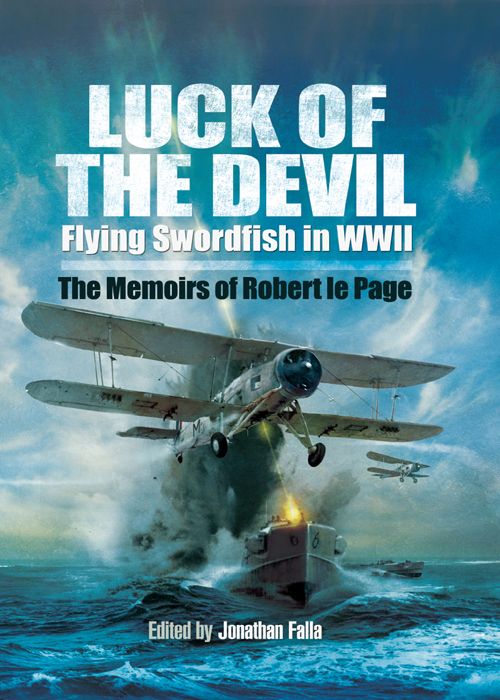

Robert Le Page, my father, grew up on a housing estate in southeast London, the son of a window cleaner. He ended his career as a distinguished professor of sociolinguistics, respected as one of the early pioneers in the study of creole languages and multi-lingual societies. Between the very different worlds of his childhood and his scholarship, there came an experience that was profound and life-changing: his years (19415) with the Fleet Air Arm, flying Swordfish in the Battle of the Atlantic and with the Arctic convoys.

He wrote his memoir of the war aged eighty, in the last years of his life (he died in 2006), having a small number of copies printed for distribution to friends and family. Never mind all the distinctions he had achieved in his career in Jamaica, Malaya, the Americas, at Singapore and at York University; never mind the numerous publications, the honorary degree, the tree-lined college court named in his honour: his Fleet Air Arm days still haunted him.

After his death, I wondered if the memoir might not find a wider audience. When I came to edit it, I found that there were errors and gaps, but also that these could be filled from other sources: from a number of letters he had written to me over the years; from passages in his later academic autobiography; from many hours of conversation I had had with him over the course of four decades; and from the recollections of his wife, Gina. In 1991, the surviving 1940s aircrew of 816 Squadron held a reunion, and a booklet was put together including Robert's poems about the squadron, and various other items, in particular brief accounts by Don Ridgway and Brian Bennett, some parts of which Robert then inserted with permission into Luck of the Devil .

By foraging among these various sources, I was able to fill the lacunae and to add some extra information to clarify contexts. So, for example, the memoir mentions that, flying their Swordfish from Thorney Island on the south coast to Macrihanish on the Mull of Kintyre, the squadron fell in with a wild party held at an airbase somewhere halfway but Robert gives no more detail. However, in July 1998 I was working on a novel of my own, in part concerning Polish aircrew in wartime Britain, and I asked Robert if he had encountered any. The story of the party and the painful Polish New Year greeting (p.76) is contained in the letter I received in reply.

Other episodes are more problematic, and clearly there are questions of recall. Some memoirs of the Second World War often give an impression of crystal-clear recollection right down to details of conversation. There is a common perception that very elderly people who can scarcely remember what they had for breakfast will nonetheless display a perfect clarity regarding events seventy years ago. How correct are such memories, in truth? Often it is impossible to know; the vividness of a story is no guarantee of its accuracy.

A curious example of this occurs in , in which Robert speaks of working on a financial audit for the Saunders-Roe Company at Cowes in 1939, and seeing there a huge flying boat under construction, the SaRo Princess. He relates the circumstances carefully, noting a colleague who was present and what had been said. But this story cannot be true: the Princess flying boat was barely even sketched out until mid-way through the war, was not ordered by BOAC until 1945, and did not make a test flight until 1952. Robert cannot have seen it in 1939, because it did not exist. There is a possibility that, immediately after the war and while waiting to go up to Oxford, he did some small audit work on Saunders-Roe for his old accountancy firm, and I thought for a moment that perhaps he was confusing a pre-war with a post-war memory. But even that is problematic, since this would have been in 1945 at the latest, when I believe little of the huge flying boat had yet been built. I considered removing the passage entirely, but I have left it in: he saw something, it made an impact upon him, and it surely contains a truth that I have not yet properly located.

Elsewhere his memories leave me negotiating with the chronology. In several conversations over the years, and also in a letter to me, he related another incident in which in the autumn of 1941 he (as observer) and his pilot were jumped by a Polish-piloted At the bottom of the page he adds a note. He has just phoned an old squadron friend who says, no: the Poles were based at Errol, just round the corner on the Tay (an airfield I can see today from the hill behind my house, and which is used for Sunday car boot sales). But when I look at the various websites documenting Scottish Second World War airfields, and also the history of the Polish squadrons of the RAF, I find that a ) Errol airfield was not opened until 1942; and b ) that there was a Polish fighter squadron 309 Land of Czerwien based at Crail, but only from June to October 1942, by which time Robert was with the newly reforming 816 Squadron at Thorney Island near Portsmouth.

So, what to believe? I can hardly think that he has made the whole episode up (including the corroboration from his squadron colleague). But it doesn't seem to fit. Documents that would help resolve the issue are Robert's personal flying logbooks but, as he relates, these are at the bottom of the sea, lost in the sinking of HMS Dasher . In the absence of any better solution, I have left the episode dated during his training at Arbroath, perhaps to be more fully explained another day.

For there may be other explanations. One thing I have learned while working on this memoir is that it is not only Robert's memory that is sometimes erratic, nor is it always him who is wrong. There is a doubt, for instance, over his memory of a shipbuilder's plaque (see p.75): there are a number of websites such as the Fleet Air Arm Archive that document the history of the FAA's escort carriers, of which Robert served on four: HMS Dasher, Tracker, Chaser , and Empire McCabe , and they all agree that Dasher was not built by the company Robert believed. If, however, I enquire as to where th e Empire McCabe was built, most sites concur that she was built by Swan Hunter on the Tyne, but one source demurs, saying that the builder was Harland & Wolff of Belfast. Given that websites are by no means primary sources, and tend to follow each other's lead, I don't think that the outvoting of Belfast is conclusive. Somebody clearly has it wrong and that may also be true of the information on Fife airfields and Polish squadrons.

Next page