Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For JFA

That is what we are supposed to do when we are at our bestmake it all upbut make it up so truly that later it will happen that way.

E RNEST H EMINGWAY

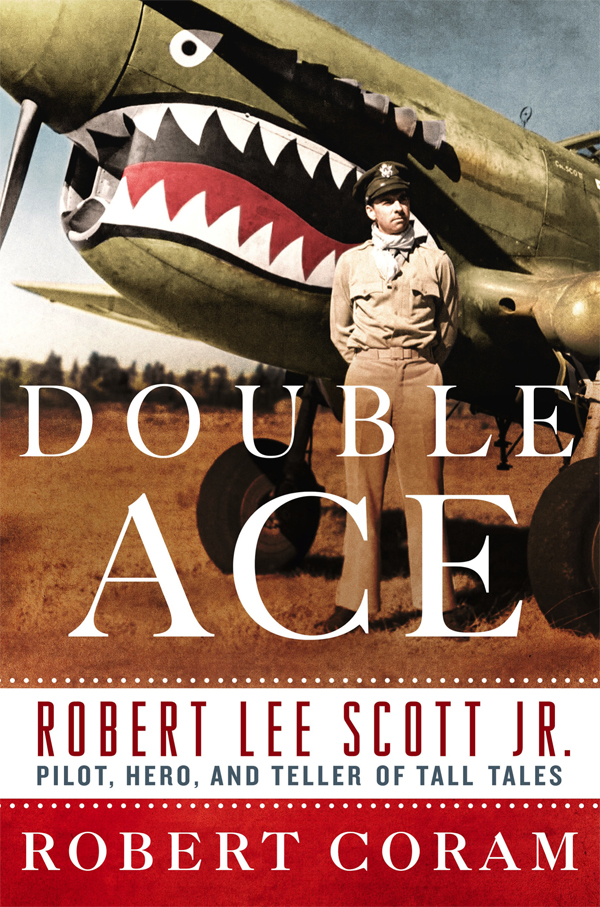

Robert Lee Scott Jr. was a hero.

He flew into battle alone against the enemies of his country, and he emerged victorious. He also wrote one of the most important books of his time, a book that influenced the lives of thousands. For a time in the mid-1940s, Robert Scott was one of the most famous people in America.

Fighter pilot. Hero. Famous author. Scott was these and many other things.

He was a man who talked too much and with too little regard for the truth. He was an inveterate and dazzling storyteller, a devilish charmer, and a roguish fellow who had more than a little of the carnival barker in his makeup.

He was a professional Southerner, a lifetime performance artist who, in telling stories of his adventure-jammed life, often left facts behind and cavorted through vales of hyperbole, believing, as do many Southerners, that the story would become true in the telling.

Mothers influence their sons in ways both beneficial and burdensome. Scotts mother wanted her firstborn son to be famous, and with words like velvet-sheathed blades, she poked and prodded him until he achieved her great desire.

Nothing could be commonplace for Scott; events had to be dramatic, obstacles had to be mountainous, and enemies had to be so powerful that when he triumphedas was his destinyScotts mother would nod in approval.

Scott had two younger siblingsa sister and a brotherand they would say that Rob (the family called him Rob) was an only child; that from the time he was born, he was his mothers life, and that they grew up almost as outsiders in their family.

Scotts motherhe called her Mamawas a teacher forced by marriage into the role of housewife, and what energy she had left after cleaning and dusting and cooking and scrubbing, she used to drive Rob toward greatness.

Scott responded well to his mamas admonitions. All his life he would add extra effort to whatever chore was set before him. Doing a job well was not enough; every job had to be perfect, because his mama expected perfection. Of course, perfection is impossible and thus Scott, from an early age, was afflicted with an itch that could not be scratched, an ambition that could not be satisfied, and a hope that could not be fulfilled. For Rob, the inevitable failures of childhood became lifelong scars.

Robert Scott and his oversized personality came out of an undersized town: Macon, Georgia, a piddling and nondescript town in the middle of the state where wind sighs in the tall pines, the heat of the sun is fierce, and people see visions in cloud formations.

In Macon, the favorite pastime was replaying battles from what the locals called the War of Northern Aggression; that, and worshipping ancestors who had served the Glorious Cause. The town was barely touched by the Civil WarSherman had fired a few shots in that direction to keep Macons militia in place as he raced past en route to Savannahbut the towns inhabitants preferred to believe that they had been invaded and ravished; that because of Shermans assault, the chickens stopped laying eggs and the cows stopped giving milk. Generations of Macons children grew up obsessed by the Civil War and roiling with ever-fresh anger at the Damnyankeesa phrase expressed by Southerners as a single word to show their everlasting contempt.

Given that Scotts first and middle names came from Robert E. Lee, one of the most venerated men in Southern history, he would have been horrified at being compared to a Yankee general, especially a man as vilified in Georgia as William Tecumseh Sherman. But the comparisons are many and cannot be denied.

Both men spewed so much verbiage that their words distort their historical image.

Both men were dramatic and theatrical.

Both men were inveterate womanizers who felt considerable remorse late in life for their weakness.

Both men were prone to lengthy and debilitating bouts of depression.

Both men loved geography and had a genius for knowing and remembering terrain, an invaluable gift in war.

Both men can be considered gifted to the point of genius in their individual fields of warfare: Sherman laid waste to a large part of southeastern America. Scott laid waste to enemy forces in the air and on the ground in southeastern China.

Finally, both men were warriors, and warriors must be judged by their deeds in war, not by their human frailties. Sherman and Scott were among the most brilliant soldiers of their times in their separate wars.

Like it or not, Sherman and Scott were two peas in the same pod.

* * *

An invisible wall built with bricks of prejudice and sealed with the mortar of inferiority surrounded Macon, and about the best a Macon boy could hope from life was mediocrity. But you would never know this by the attitude of local boys. They rolled their shoulders, hustled their testicles, and looked around with angry and defiant eyes, ready to take on all comers. They would tell you in a heartbeat that they were as good as any sumbitch from New York City and that they could do anything in life that they wanted to do. But deep inside, in words that were never spoken, they believed that only the wealthy and privileged ever climbed the invisible wall.

Scott, pushed by his mother, resolved early in life that not only would he climb the wall, he would travel farther, fly higher, and do greater things than anyone from Macon had ever done; he would do all this and more, by God.

And he did.

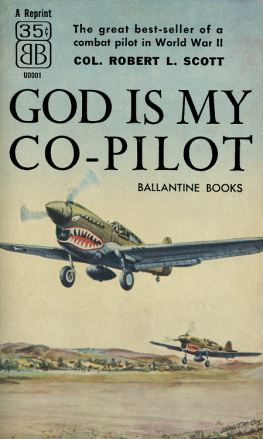

In World War II, he was an Army ace, a bona fide national hero at a time when America so desperately needed heroes. He came home in early 1943 as Americans waited for their country to invade Europe. Scott traveled America making speeches to galvanize defense workers, to support the war effort, and to encourage people to buy war bonds to finance the war. His speeches were war stories from far-off China, and pictures of the time show hundreds of people staring at him with enthralled looks on their faces. During his speech-making tour a host suggested he write a book about his combat experiences. He was too busy to write, but he was a talker, so he took off three days to dictate a book. God Is My Co-Pilot sold hundreds of thousands of copies and influenced several generations of boys to become pilots. It was one of the most famous books of the time, and it was made into an iconic movie that is still aired on late-night television.

For decades Scott was trailed by big-name journalists who wanted to write down every word he spoke, by adulatory young people who wanted to gaze upon this mythic man, and by Hollywood movie stars who wanted to borrow the luster that his company would bring to their careers; that and more these movie stars wanted.

The wonder of all this, to paraphrase Dr. Samuel Johnson, was not so much that Scott did these things well, but that he could do them at all. Scott was the most unlikely of men to achieve such success. His intellect was as average as his ability. He was a small-town Southerner who had the values and the insecurities of a small-town Southerner. In addition, Scott spent much of his life running from and covering up the shame of flunking out of high school. His failure to meet even this minimum level of achievement was a lifelong embarrassment. Even when he was an old man and famous, he did not care to speak of that crippling experience.