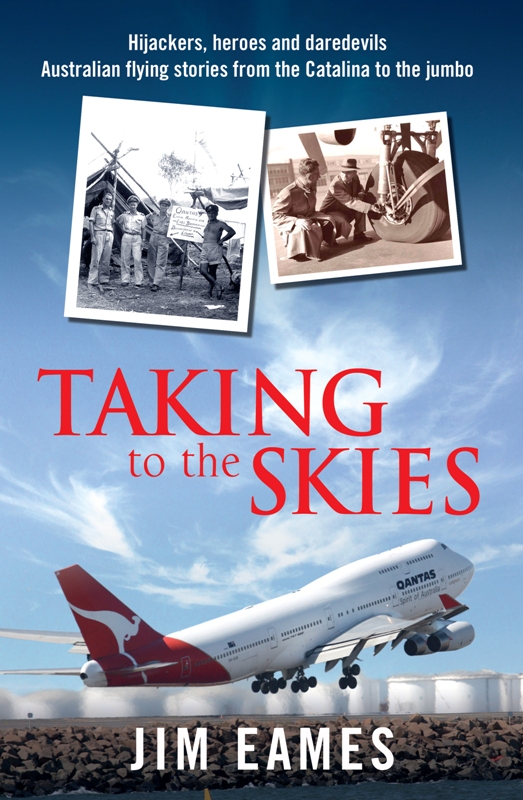

To our Benjamin and a proud Australian heritage

Taking to the Skies

Daredevils, heroes and hijackers

Australian flying stories from

the Catalina to the Jumbo

JIM EAMES

First published in 2014

Copyright Jim Eames 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 174331 594 1

eISBN 978 174343 344 7

Set in 12/17 pt Berkeley Oldstyle by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Contents

This book came out of a desire to revisit events which have marked significant landmarks in Australian aviation, primarily since the Second World War. Some of these events, seen in isolation, might have been well recognised at the time, but the recollections of them have faded over the years. Others provide a sometimes surprising insight into Australias involvement in aviation, both domestic and international. Others still have remained largely unknown.

In some instances gathering them together has produced unusual results. For instance, not many these days would be aware that Australia has experienced no fewer than five aircraft hijackings, the first of which occurred years before hijacking itself was to become established as the weapon of choice by terrorists in the Middle East and elsewhere. Two of these crimes resulted in the deaths of the hijackers.

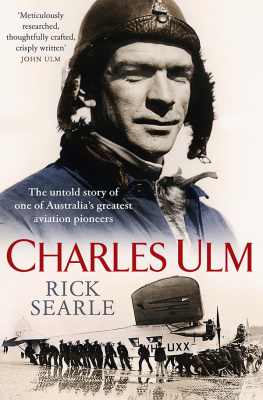

The use of the Second World War as a starting point is deliberate, and for several reasons. First, hundreds of thousands of words have been written, many of them in quite recent years, of the achievements of aviators like Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, Charles Ulm and Bert Hinkler, who have become household names. Through such men, Australia punched well above its weight in the international aviation-pioneering sphere, a fact easily demonstrated by one simple statistic.

All of the major oceans of the world, with the exception of the Atlantic, were first crossed by Australians: Kingsford Smith and Ulm tamed the Pacific in 1928, then crossed the Tasman the same year. Three years later, in October 1931, Hinkler crossed the South Atlantic Ocean west to east from New York via Jamaica, Africa and Europe to London. P.G. Taylor crossed the Indian Ocean from Port Hedland to Africa in 1939 and followed that up postwar by crossing the South Pacific from Sydney to Chile in 1951. And the last remaining ocean, the Atlantic, did not go unchallenged by Australians. In May 1919, long before the exploits of his fellow pioneers, Harry Hawker set out on the first attempt to cross the Atlantic nonstop, only to crash-land at sea when his engine overheated.

All of these larger-than-life characters left a legacy of achievements for other Australians to build upon, but the legends they created often left large shadows, shadows which occasionally tended to obscure the feats of those who followed as the aeroplane became a more familiar part of our lives.

The use of the Second World War as a starting point is important for another reason. In the six years of war the advances in aircraft design and engine development were little short of remarkable. What had been largely a biplane era of wood, wire and fabric up to 1939 had morphed by 1945 into high-performance fighters, like the Mustang, and bombers, like the Lancaster and the B-29 Superfortress, while military transports, such as the Douglas DC-4, were destined to launch a postwar civil role as airliners. Meanwhile, in the background was the hissing sound of the jet engine, soon to sweep all before it in terms of speed and efficiency.

Whichever way its looked at, change has been the one constant in aviation since 1945, not simply in the aircraft themselves but in the people who have been part of the industry and the way they have gone about their businessalthough much of the industry today is unrecognisable from that which existed even in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

The war also represented a changing of the guard in aviation leadership, with a war-torn United Kingdom struggling to regain its prewar eminence alongside a United States which had ended the war with unassailable advantages in aircraft production and manpower. It was therefore the United States which convened the Chicago conference of 1944 resulting in the creation of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which would go on to establish the guidelines for the operation of post-war aviation.

Fortunately, in keeping with the original contributions of our early pioneers, Australia had a seat at the table as a member of the governing council of the ICAO when it gathered in Chicago in 1947in itself a credible achievement for a country with such a small population.

But while Australias international contribution would be important, its own industry at the far end of the earth from engine and air-frame manufacturers (such as Boeing, Douglas and Lockheed), not to mention those producing smaller aircraft, had to ensure it had the expertise on its own continent to keep aircraft flying. That essential requirement bred a talent pool the equal, and in some cases superior, to anywhere else in the world. There was little alternative. Taking an aircraft all the way back to the United States even for an essential factory fix was not an economic option. Added to a self-reliance would be an innovative streak which would lead to breakthroughs not only in engineering techniques but across other parts of the industry, from important roles in the development of aspects of air-traffic control, navigation and landing aids in worldwide use, to adaptions such as the combination escapeslide raft subsequently to be fitted as standard equipment on aircraft like the Boeing 747.

Terrain also played a part, particularly when it came to the training of aircrew. Finding your way across a featureless outback without recourse to navigational aids of any sort called for astute observations and attention to detail. Connellan Airways pilots flying out of such places as Alice Springs, in part earned their wings by creating mud maps of ground features, such as dry creek junctions and water bores, which they used to plot their course to isolated stations. Today any such course would be a brief input into a GPS.

When it came to learning the hard way, most postwar pilots will tell you nothing approached the advantage of having Papua New Guinea on our doorstep. Picking their way through treacherous gaps between 3650-metre mountains, or landing on short airstrips with uphill gradients ending in a cliff face at the top, left little margin for error. As one pilot who would later become a senior check captain on Boeing 747s explains: You learned to operate an aeroplane on the mainland. You learned to

Next page