CONTENTS

In memory of my mother, Ethel Spector Davis

INTRODUCTION

A MERICANS ARE ACCUSTOMED TO THINKING OF WORLD WAR II AS having ended on August 14, 1945, when Japan surrendered unconditionally. The finality of this action seemed to be appropriately symbolized in the solemn ceremony aboard the USS Missouri on September 2 in which Japans representatives signed the instrument of surrender under the watchful eyes of General MacArthur and in the shadow of the Missouris sixteen-inch guns.

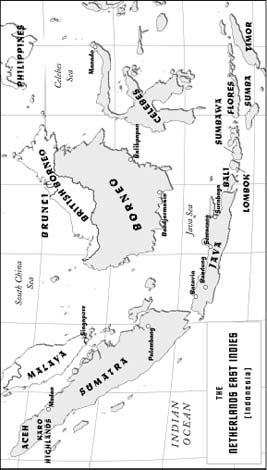

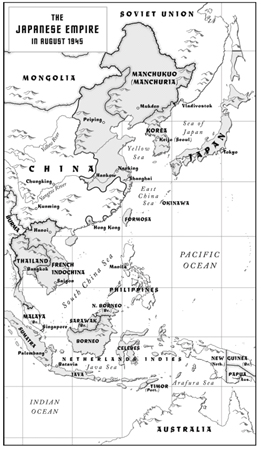

That was the end of the war so far as most Americans were concerned. Yet on the mainland of Asia, in the vast arc of countries and territories stretching from Manchuria to Burma, peace was at best a brief interlude. In some parts of Asia, such as Java and southern Indochina, peace lasted less than two months. In China, a fragile and incomplete peace lasted less than a year. In northern Indochina, peace lasted about fifteen months, and in Korea, about three years. Indeed, 194546 in Asia may have appeared to many not as a time when war ended, but as a time when the various protagonists switched sides.

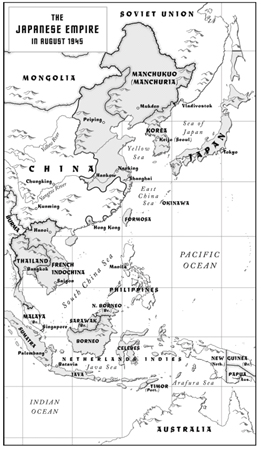

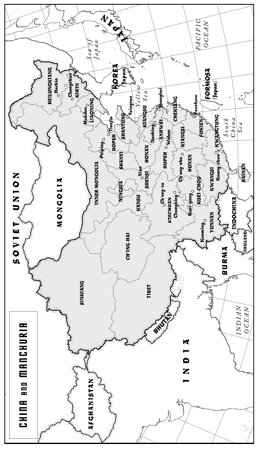

Why did peace in Asia prove so elusive? What were the elements that contributed to the long postwar years of grim struggle during which many suffered far more than they had during World War II itself? This book attempts to address these questions through an examination of events in five countries that previously formed a part of the Japanese Empire. With one exception, they were places in which things went disastrously wrong and gave birth to long-term problems that sometimes outlived the Cold War. This is largely a story about military occupations and their consequences. After the American experience in Iraq it is unnecessary to explain that military occupations that follow on the complete disruption of a countrys old order are often ill-conceived, confused, messy affairs that can result in unforeseen consequences for both the occupied and the occupiers. At the conclusion of the war against Japan, the victorious AlliesBritain, China, the United States, and the USSRall sent troops to occupy or reclaim vast areas of mainland Asia that had formed part of Japans empire.

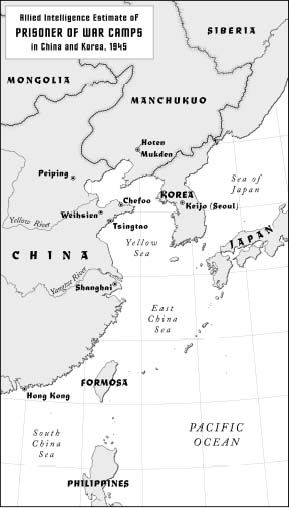

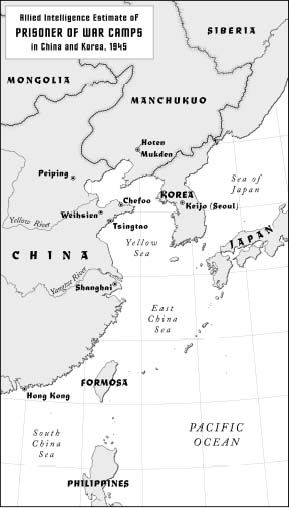

The British and Americans saw their most important task as disarming the Japanese military forces in China, Korea, and Southeast Asia and sending them back to Japan. Another pressing concern was to liberate thousands of Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees who had been starved, beaten, and otherwise ill treated by the Japanese in prison camps throughout Asia. The greatest threat to these policies was anticipated to be the Japanese. Most of their well-armed forces on the mainland of Asia had never suffered any direct military setbacks and could not be counted on to behave as a defeated enemy. In addition, die-hard Pan-Asianists and former members of the secret police and intelligence organizations might stay on to help stir up trouble among the local populations.

The Chinese and Soviets also saw the occupations as an opportunity to assert what they believed to be their historic rights and interests in East Asia. For the Americans and the British, it was simply a matter of reestablishing stability and order through the implementation of policies recently agreed upon by the Allies. Few anticipated that the Japanese forces themselves might be utilized to help in the restoration of order through those policies, or that local people would seriously oppose them.

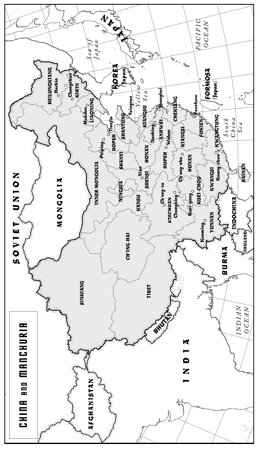

All of the soldiers who brought their various versions of liberation to the countries of Greater East Asia were members of famous military units, veterans of the most difficult campaigns of World War II. They were unprepared for their new role as occupiers and had at best an imperfect knowledge of the places they were going. They wanted most to go home. Their governments were often little better prepared, and these soldiers would soon become acquainted with the consequences of ignorance, inattention, and indecisiveness in London, Moscow, and Washington. Their theaters of operation were the countries of Japans former empire of Greater East Asia, built on the wreckage of the European colonial empires they had defeated and occupied in 1942.

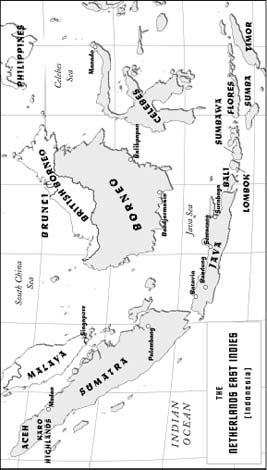

The British, French, and Dutch colonial empires that had been displaced by the Japanese with unexpected ease and dispatch had themselves been relatively recent creations, despite their pretensions to age and permanence. So were the Japanese colonies in Korea and Manchuria. The final French conquests in Indochina had ended only in the 1880s. The Dutch had added sizable portions of the Indonesian archipelago, including Kalimantan, Bali, and Sumatra, to the Netherlands Indies only in the mid-to late nineteenth century and were still battling stubborn resistance forces in Aceh into the early twentieth century. In Korea, many were still alive in 1945 who could remember Korea as an independent state. The world was fluid and about to be remade, recalled an American journalist. An empire had vanished. A half dozen victors raced for the spoils. More than a half dozen; for old class antagonisms, regional rivalries, ethnic and religious conflicts were still alive. They had survived both European colonialism and the Japanese imperial project, although sometimes in new or altered form. The war and the Japanese conquest transformed political and personal alignments, ideologies, and institutions in the nations that became part of Greater East Asia, but the basis of postwar suspicions, and ambitions, remained.

CHAPTER ONE

SHOOT THE WORKS!

N O ONE EXPECTED THE WAR TO END WHEN IT DID. EVEN AFTER the two atomic bombs and the entry of the Soviet Union into the war on August 9, the Japanese, though doomed, were expected to fight on for some considerable time. Suddenly, on August 10, the Domei News Agency broadcast a statement by the Japanese Foreign Ministry that Japan was ready to accept the surrender terms presented by the Allies in the so-called Potsdam Declaration on July 26, provided that the said declaration does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler. The announcement surprised even top officials in Washington. When the Japanese surrendered it caught the whole goddamn administrative machinery with their pants down, recalled a colonel in the Army high command.

Next page