This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2015 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact ,

or write us at the above address.

Copyright Tim Spector 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1284-3

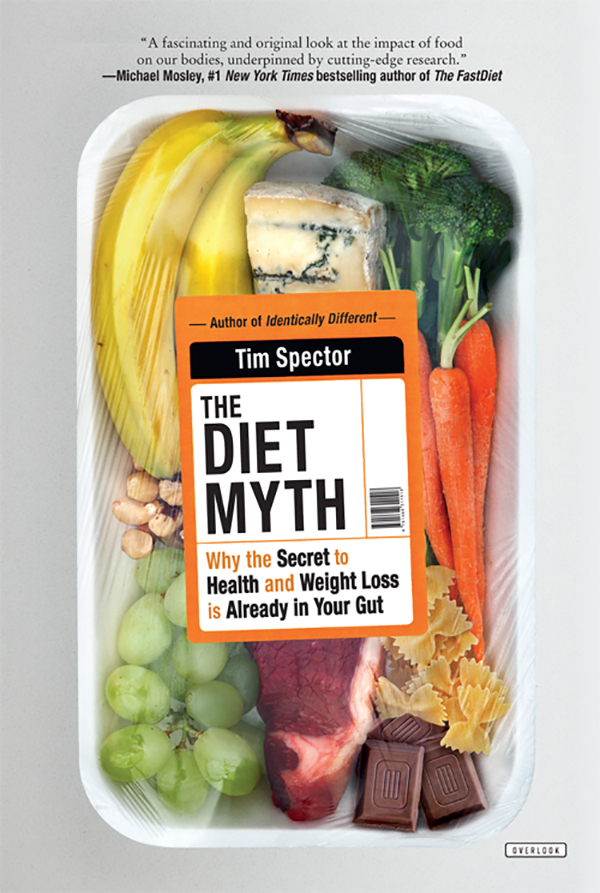

THE

DIET MYTH

Why the Secret to

Health and Weight Loss

is Already in Your Gut

Tim Spector

W hat should we eat to stay healthy and slim? Its a simple question that still bewilders us, despite a seemingly infinite amount of available information. Most diet plans prove to be only short-term solutions, and few strategies work for everyone. Why can one person eat a certain meal and gain weight, while another eating the same meal drops pounds? Part of the truth lies in genetics, but more and more, scientists are finding that the answer isnt so much what we put into our stomachs, but rather the essential digestive microbes already in them.

Drawing on the latest science and his teams own pioneering research, The Diet Myth breaks down common misconceptions that fuel weight-loss fads by exploring the hidden world of the microbiome. World-class geneticist Tim Spector demystifies the latest information on fat, calories, vitamins, and nutrients. Mixing cutting-edge discoveries, illuminating science, and his own pioneering research on the genetics of twins, Spector reveals why we should abandon fads and instead embrace a diverse diet in order to lose weight, keep a healthy stomach, and nourish our bodies.

Identically Different

Your Genes Unzipped

To my family and other microbes

It had been a tough climb: six hours walking up 1,200 metres to the summit on touring skis with artificial sealskins to stop us sliding backwards on the snow.

Like my five companions I was feeling tired and a bit light-headed but I still wanted to check out the spectacular view at 3,100 metres over Bormio on the ItalianAustrian border. We had been ski-touring in the area for the past six days, staying in high-altitude mountain lodges, enjoying plenty of exercise and good Italian food. We took our skis off to walk the ten metres to the top but I felt unsteady and didnt go all the way to look over the edge, thinking my mild vertigo was kicking in. As we turned to ski down, the weather deteriorated, clouds descended and light snow began to fall. I had trouble seeing the tracks ahead of me but assumed it was my old goggles misting up. Usually skiing down is the easy relaxing part, but I was strangely tired and relieved an hour later when we reached the bottom.

When I caught up with our French mountain guide, he pointed out a large tree fifty metres away with two alpine squirrels in it. I could see the squirrels, but I could see four of them two diagonally above the others and realised I was seeing double. From my days as a junior doctor in neurology I knew the three likely causes at my age, none of them good: multiple sclerosis, brain tumour or stroke.

After a stressful few days back in London when I managed to organise an MRI brain scan, which, luckily, didnt show anything that suggested the two other unpleasant causes, I was still left with the possibility that Id suffered a small stroke.

Eventually, an ophthalmologist colleague was able to diagnose me over the phone with a fourth cranial nerve occlusion. I had only vaguely heard of it, but the good news was that it usually improved within a few months without treatment. The exact cause is unknown but it involves a spasm and constriction and micro-blockage of the artery supplying this nerve, which in turn controls some of the eye movements. It was a great relief. I just had to wait for the eye to return to normal and wear initially a patch and then some nerdy-looking glasses with prism lenses to help reduce the blurring.

I couldnt read or use my computer for more than a few minutes at a stretch and, to complicate things, I had developed high blood pressure. This puzzled my expert colleagues as blood pressure is not supposed to change so suddenly, but I knew mine definitely had, as, by chance, I had measured it myself two weeks before. After many cardiac tests to exclude rare causes I was given anti-hypertensive drugs and aspirin to thin my blood.

In the space of two weeks I had gone from a sporty, fitter-than-average middle-aged man to what felt like a pill-popping, hypertensive, depressed stroke victim. With the enforced time off work as my vision slowly improved I had plenty of opportunities for contemplation.

This was the wake-up call I needed to reassess my own health, and sent me on a personal odyssey not only to understand how to improve my chances of living longer and better but also to reduce my dependence on prescribed drugs and find out if by altering the food I chose to eat I could become healthier. I thought changing my lifelong dietary habits would be my greatest challenge but it turned out that finding out the truth about food was an ever greater one.

The myth of modern diets

Trying to work out what is good or bad for us in our own diets is increasingly difficult, even for me as a doctor and scientist who has studied epidemiology and genetics. I have written hundreds of scientific papers on different aspects of nutrition and biology but have found it hard to make the shift from general advice to practical decisions. Confusing and conflicting messages are everywhere. Knowing who and what to believe is a big problem. While some diet gurus tell us to graze by eating regular small meals and snacks, others disagree and encourage, say, skipping breakfast, eating a big lunch or avoiding heavy meals at night. Some promote eating one thing (such as cabbage soup) to the exclusion of others, while theres a French diet cleverly called le forking which claims that by using only a fork to eat the pounds will fly off.

Over the past thirty years almost every component of our diet has been picked on as the villain by some expert or other. Despite this scrutiny, globally our diets continue to deteriorate. Since the 1980s, when the links between high cholesterol and heart disease were first uncovered, the idea that a healthy diet has to be low-fat has taken hold. Most countries have reduced their official recommendations for the amount of total calories consumed as fat, particularly meat and dairy products. Reducing fat meant increasing carbs. This has been the mainstay of medical advice and, superficially at least, seemed to make sense, since fat packs twice the amount of calories per gram as carbohydrates.

In contrast to this official line, diet plans of various levels of complexity such as the Atkins, Palaeolithic and Dukan Diets, which have become popular since the early 2000s, all urge people to stop indulging in carbohydrates and to eat only fat and protein. The glycaemic index (GI) diet targets certain types of carbohydrates that via the release of glucose rapidly raise blood insulin, seen as the main enemy, and the South Beach Diet targets both bad carbs and bad fats; some diets (such as the Montignac) forbid certain food combinations, and the recent phenomenon of fasting (such as the 5:2 diet) promotes as the answer intermittent fasting via periods of reduced calorie intake. And there are countless alternatives I was shocked to find well over thirty thousand books available, with their own websites and merchandising, promoting different diet regimes and supplements ranging from the sensible to the dangerous and crazy.