Tim Spector

THE DIET MYTH

The Real Science

Behind What We Eat

To my family and other microbes

Contents

It had been a tough climb: six hours walking up 1,200 metres to the summit on touring skis with artificial sealskins to stop us sliding backwards on the snow.

Like my five companions I was feeling tired and a bit light-headed but I still wanted to check out the spectacular view at 3,100 metres over Bormio on the ItalianAustrian border. We had been ski-touring in the area for the past six days, staying in high-altitude mountain lodges, enjoying plenty of exercise and good Italian food. We took our skis off to walk the ten metres to the top but I felt unsteady and didnt go all the way to look over the edge, thinking my mild vertigo was kicking in. As we turned to ski down, the weather deteriorated, clouds descended and light snow began to fall. I had trouble seeing the tracks ahead of me but assumed it was my old goggles misting up. Usually skiing down is the easy relaxing part, but I was strangely tired and relieved an hour later when we reached the bottom.

When I caught up with our French mountain guide, he pointed out a large tree fifty metres away with two alpine squirrels in it. I could see the squirrels, but I could see four of them two diagonally above the others and realised I was seeing double. From my days as a junior doctor in neurology I knew the three likely causes at my age, none of them good: multiple sclerosis, brain tumour or stroke.

After a stressful few days back in London when I managed to organise an MRI brain scan, which, luckily, didnt show anything that suggested the two other unpleasant causes, I was still left with the possibility that Id suffered a small stroke.

Eventually, an ophthalmologist colleague was able to diagnose me over the phone with a fourth cranial nerve occlusion. I had only vaguely heard of it, but the good news was that it usually improved within a few months without treatment. The exact cause is unknown but it involves a spasm and constriction and micro-blockage of theartery supplying this nerve, which in turn controls some of the eye movements. It was a great relief. I just had to wait for the eye to return to normal and wear initially a patch and then some nerdy-looking glasses with prism lenses to help reduce the blurring.

I couldnt read or use my computer for more than a few minutes at a stretch and, to complicate things, I had developed high blood pressure. This puzzled my expert colleagues as blood pressure is not supposed to change so suddenly, but I knew mine definitely had, as, by chance, I had measured it myself two weeks before. After many cardiac tests to exclude rare causes I was given anti-hypertensive drugs and aspirin to thin my blood.

In the space of two weeks I had gone from a sporty, fitter-than-average middle-aged man to what felt like a pill-popping, hypertensive, depressed stroke victim. With the enforced time off work as my vision slowly improved I had plenty of opportunities for contemplation.

This was the wake-up call I needed to reassess my own health, and sent me on a personal odyssey not only to understand how to improve my chances of living longer and better but also to reduce my dependence on prescribed drugs and find out if by altering the food I chose to eat I could become healthier. I thought changing my lifelong dietary habits would be my greatest challenge but it turned out that finding out the truth about food was an ever greater one.

The myth of modern diets

Trying to work out what is good or bad for us in our own diets is increasingly difficult, even for me as a doctor and scientist who has studied epidemiology and genetics. I have written hundreds of scientific papers on different aspects of nutrition and biology but have found it hard to make the shift from general advice to practical decisions. Confusing and conflicting messages are everywhere. Knowing who and what to believe is a big problem. While some diet gurus tell us to graze by eating regular small meals and snacks, others disagree and encourage, say, skipping breakfast, eating a big lunch or avoiding heavy meals at night. Some promote eating one thing (such as cabbage soup) to the exclusion of others, while theres a French dietcleverly called le forking which claims that by using only a fork to eat the pounds will fly off.

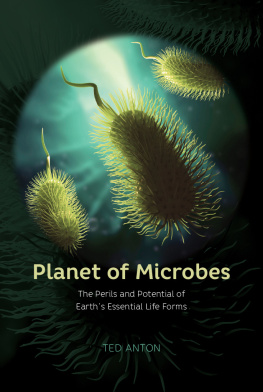

Over the past thirty years almost every component of our diet has been picked on as the villain by some expert or other. Despite this scrutiny, globally our diets continue to deteriorate. Since the 1980s, when the links between high cholesterol and heart disease were first uncovered, the idea that a healthy diet has to be low-fat has taken hold. Most countries have reduced their official recommendations for the amount of total calories consumed as fat, particularly meat and dairy products. Reducing fat meant increasing carbs. This has been the mainstay of medical advice and, superficially at least, seemed to make sense, since fat packs twice the amount of calories per gram as carbohydrates.

In contrast to this official line, diet plans of various levels of complexity such as the Atkins, Palaeolithic and Dukan Diets, which have become popular since the early 2000s, all urge people to stop indulging in carbohydrates and to eat only fat and protein. The glycaemic index (GI) diet targets certain types of carbohydrates that via the release of glucose rapidly raise blood insulin, seen as the main enemy, and the South Beach Diet targets both bad carbs and bad fats; some diets (such as the Montignac) forbid certain food combinations, and the recent phenomenon of fasting (such as the 5:2 diet) promotes as the answer intermittent fasting via periods of reduced calorie intake. And there are countless alternatives I was shocked to find well over thirty thousand books available, with their own websites and merchandising, promoting different diet regimes and supplements ranging from the sensible to the dangerous and crazy.

I wanted to find a formula that would keep me healthy and reduce the risks or symptoms of the most prevalent modern diseases. But most popular diet plans focus on reducing weight rather than other health and nutritional aspects. Some people are overweight yet suffer few adverse metabolic consequences, while others are apparently lean with little fat under their skin but have fat around their inner organs, with disastrous consequences for their health. But scientists still dont understand why this happens.

The ritual of dieting has become an epidemic. A fifth of the UK population are on some form of diet at any one time, yet we continueto expand our waistlines by an inch every decade. The average male and female Briton now has a 38-inch and 34-inch waist respectively and both are still increasing, leading to more and more related health issues like diabetes and knee arthritis and even breast cancer, the rate of which increases by a third for each increase in trouser and skirt size. While 60 per cent of Americans would like to lose weight, only a third actually bother any more a significant reduction from twenty years ago. The reason is that most people dont believe the weight-reducing diets actually work. Surrounded by increasingly plentiful and cheap food, and harsh memories of failed attempts at dieting, we often lack the willpower to reduce our calorie intake and to exercise more. There is even some evidence that an endless cycle of failed diets, where weight drops and rebounds regularly, can actually make people fatter. Some of the popular diets clearly work for many of us in the short term, especially the low-carb, high-protein ones, but longer term it seems to be a different story. The evidence suggests that even with record-breaking dieters, the weight often slowly piles back on.

Bad science and increasing waistlines

Next page