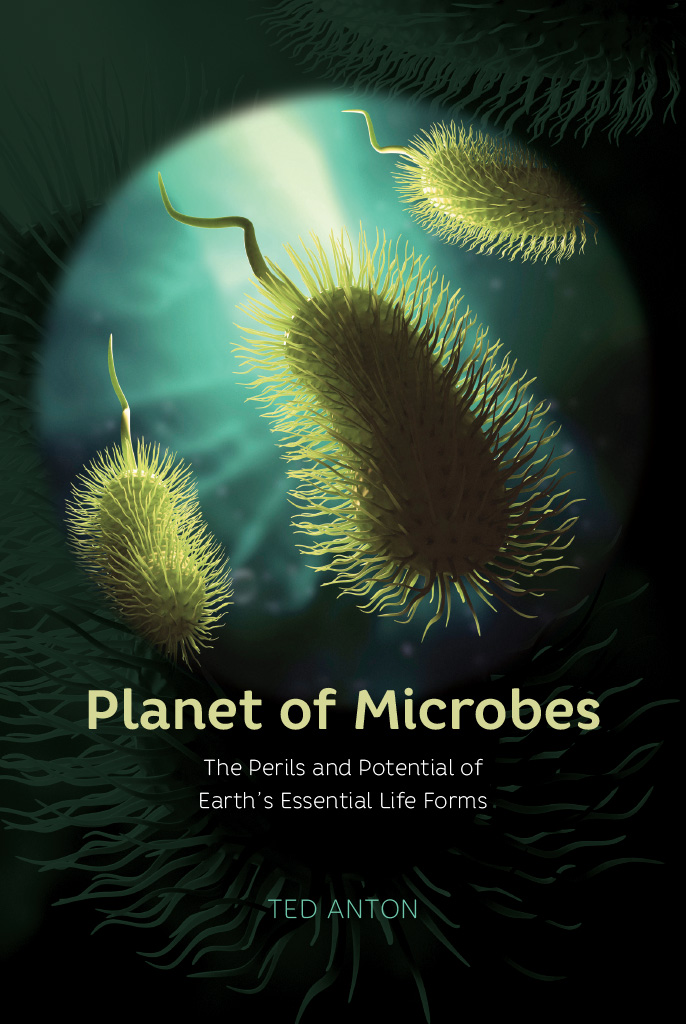

Planet of Microbes

The Perils and Potential of Earths Essential Life Forms

Ted Anton

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by Ted Anton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35394-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35413-2 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226354132.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Anton, Ted, author.

Title: Planet of microbes : the perils and potential of earth's essential life forms / Ted Anton.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017016254 | ISBN 9780226353944 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226354132 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: MicroorganismsPopular works.

Classification: LCC QR56 .A58 2018 | DDC 579dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017016254

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper)

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper)

Contents

Forty-seven-year-old Nora Noffke scanned the Australian desert at the end of a blistering day. With her Old Dominion University student Dan Christian, she was seeking evidence of ancient life. It was their second day in the national park, and some of the equipment was already covered with dust. They had gotten lost once. The leaves of acacia trees and grass stirred over rocks some three and a half billion years old. In the morning the air had smelled fresh and clean, but now, at sunset, the stench of a cow carcass rose from a nearby dry streambed.

It was July 2011, and they had taken four flights over three days from Norfolk, Virginia, to Sydney, and then to Perth. Before being allowed into the Pilbara National Park, she had to present her project to officials of the Australian Geological Survey. They flew to a coastal town and rented a four-wheel-drive Jeep to drive toward the dusty town of Marble Bar, famous for its horse race in July. Seventy-five hours after leaving Virginia, in the middle of the night, they reached the desert. Exhausted, they pushed ahead on a dirt rut that dwindled to nothing. They could see their mountain site in the distance but had no idea how to get there. It was so dark they finally pitched their tent at a homesteads crumbled foundation, too tired to go another mile.

Noffke studied the intricate, beautiful, multicolored microbial mats that live in the Earths tidal pools and salt lakes. Some protected preserves surrounding the Red Sea and some Chesapeake Bay, and some appeared in ancient sediments much earlier in Earths history than many believed complex life had existed. Other microbial biofilms helped treat wastewater. Some consumed oil spills, protected our lungs and gut, infected hospitals, and formed the plaque on our teeth. An expert in microbe mats and the sediments they altered, Noffke was one of the few researchers who believed their remains could be found in rocks in the Australian desert formed during the Earths earliest years.

For two days Noffke and Christian had hiked, hauling water tanks, food, graphs and field journals mile after mile along the rocky scree of Saddleback Ridge. Their eyes adjusted to the peculiar red landscape populated by fire ants, snakes, and a few wild cattle. It was so hot in the afternoon they covered the tent and vehicle with a tarp and huddled beneath it. But at night, as they played cards around the campfire, brilliant stars exploded over them. Two hundred million miles away a NASA rover was soon to look for the same structures on Mars, on a landscape similar to this, though far colder.

A transplant from Germany, Noffke loved field trips with her students. Her father, an air traffic controller trained by the US Air Force, taught her that people must be reminded of lifes wonders sitting right in front of them. On drives from their suburban Stuttgart home, he pointed out to her and her brother the glittering Jurassic fossils of ammonite and tiny animals in the rolling farmland. Later she studied under a supportive Harvard mentor who pioneered research into similar fossils all over the world. In her career she helped push back the dates of microbial sedimentary structures, from one to two to nearly three billion years ago, from the Middle East to South Africa and Australia. Those discoveries taught her that living microbes had inundated the ocean shallows of the earliest Earth. She had first come to Australias Pilbara in 2008 with another geologist. On their last day she had glimpsed the mat structuresbut there was no time left. She vowed to come back.

As the sun set, Dan Christian pulled out a flask of warm water . A wedge-tailed eagle swooped over the ridge in the distance. The red sun slipped to the horizon. Shadows lengthened.

Something in the boulders shadows caught her eye. She grabbed Dan and pointed. A foot-long series of parallel ridges lay in the stones. More wavy lines appeared, astonishing and beautiful. She knew those patterns! The fragments looked as if they had grown yesterday. Dan, look, there they are! Tons of them! she cried. Theyre rolled up even.

They raced toward the hill and skittered to their knees, digging and brushing in the dry earth, shouting and laughing in the fading light.

We are living through an unprecedented time of discovery about the origins of life. Huge strides have been made in our understanding of the steps by which life may have formed on Earth, and life-friendly worlds outside our solar system may be glimpsed in the near future. The heroes of this study are microbes, which dominated the Earth through most of its existence and created the oxygen we breathe and the biological processes, like respiration and metabolism, on which our lives depend.

The amazing thing is that relatives of the same ancient organisms that live in swamps and the acid waste of mines, in the hot vents at the oceans bottom and the high-radiation environments of the stratosphere, also live in our own intestinal tracts and those of farm animals. They may prove of great practical use in the remediation of radiation contamination, petroleum spills, and other toxic wastes. They convert waste into fertilizer and energy and may hold the keys to confronting the increasing rates of obesity, asthma, autoimmune diseases, and even some of our most mysterious emotional illnesses.

Most of us know something about the probiotics on the shelves of any health-food store or the microbes of the human gut. Their news feeds would be hard to miss. What we may not know is that their chemistry offers clues to the processes that gave rise to life. The anaerobic conditions of our intestines resemble some of the conditions of mining wastewater and fertilizer runoff, and some of the conditions of ancient Earth or even Mars. The fascinating research into organisms that thrive in such environments, from the hot pools of Yellowstone Park to the tops of Antarctic mountains, the acid lakes of Australia and California, backyard compost heaps, and our own bodies, hold clues to solutions of some our most intractable problems. Few animals or plants could exist without their microbes. A human body has some thirty to forty trillion. Without them, we would die.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper)

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper)