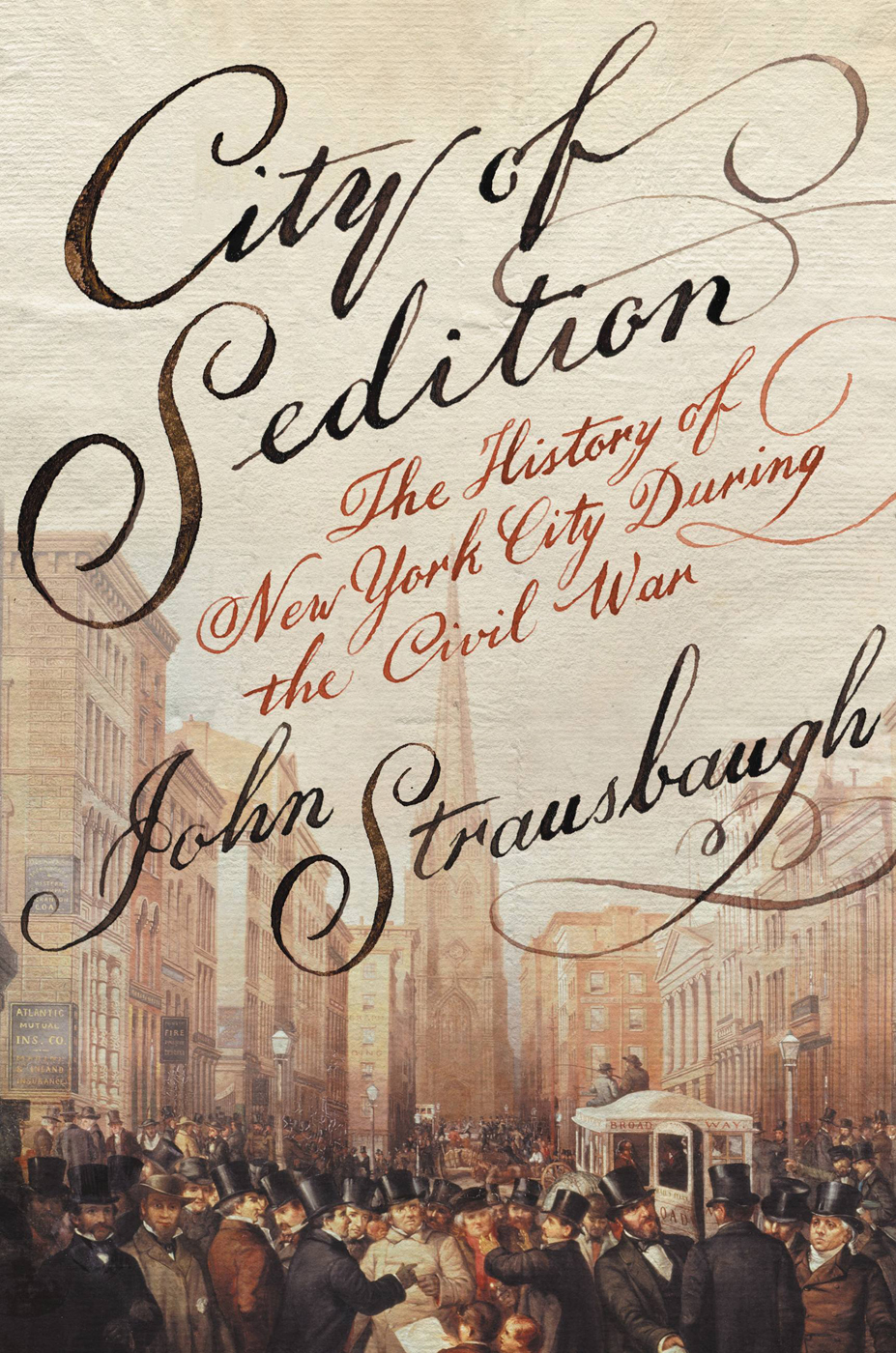

T he Civil War started in darkness. At 4:30 a.m. on Friday, April 12, 1861, batteries of the newly formed Confederate States of America commenced shelling the federal installation of Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor.

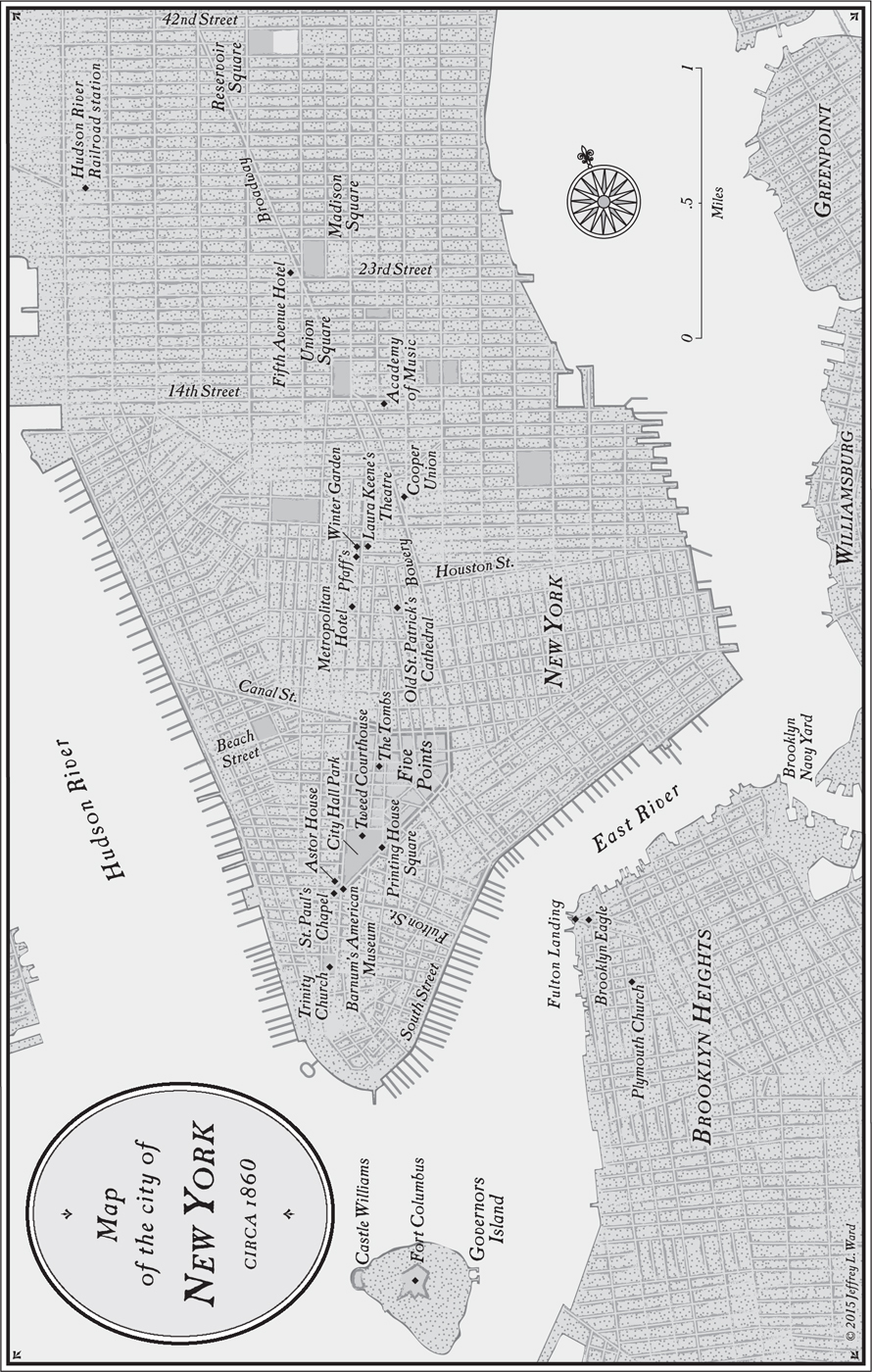

Telegraphed news of the bombardment began reaching New York Citys newspaper offices late Friday afternoon. That night, a little before midnight, Walt Whitman strolled out of the Academy of Music on 14th Street, where hed enjoyed a performance of Donizettis Linda di Chamounix. He was walking down Broadway, heading for Fulton Street where he would catch a ferry home to Brooklyn, when I heard in the distance the loud cries of the newsboys, who came presently tearing and yelling up the street, rushing from side to side even more furiously than usual. They were hawking late editions. WAR BEGUN! the New York Tribune cried. FORT SUMTER ATTACKED! The Sun chimed in.

Nearby, a group of prominent businessmen were meeting. No one in the country feared a war between the states more than New Yorks business community. They did a tremendous amount of trade with the South. Since the previous December, when South Carolina was the first state to secede after Lincolns election, theyd been studying with intense solicitude the means of preserving the peace. Theyd held numerous meetings and rallies, petitioned their politicians, pleaded with their Southern partners. War, they knew, would not only mean the end of their highly profitable trade with the Southern states. It would leave the business leaders holding more than $150 million in Southern debt. Thats the equivalent of about $4.5 billion in todays currency.

A messenger burst into the meeting and breathlessly delivered the news from Fort Sumter. The persons whom he thus addressed remained a while in dead silence, looking into each others pale faces; then one of them, with uplifted hands, cried, in a voice of anguish, My God, we are ruined!

That account was written by Morgan Dix, rector of the elite Trinity Church at the foot of Wall Street and son of the powerful political figure John A. Dix. He doesnt identify his fretful gentlemen, but their names are unimportant. They were representative of a large sector of New Yorks business elite at the start of the Civil War. As dismayed as they were, they could not have been startled by the Fort Sumter news. Conflicts between the North and the South had been festering for most of the century. Gloomy forecasts of ultimate disunion and civil war went back as far as the 1810s. Members of Congress had spent the entire decade of the 1850s alternately trying to bridge the widening sectional gulf and beating each other up over it. The moment the Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln in the spring of 1860, angry Southern fire-eaters (as Northerners dubbed the most radical and vocal pro-slavers) had made it unmistakably clear that they would consider his election tantamount to an act of war. In January, five more states joined South Carolina in seceding (Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana); in February, the six formed their own separate nation. Five more would soon join. Overnight, federal installations like Fort Sumter had become foreign military bases. When Confederate troops surrounded and blockaded the fort, hoping to starve the garrison into a bloodless surrender, Lincoln had picked up the gauntlet and sent supply ships steaming out of New York harbor. Neither side had blinked, and now the Civil War had begun.

North and South had disagreed over many issues, but Civil War historian James McPherson argues that only one was combustible enough to ignite a war between them: slavery. In the first half of the 1800s, as Northern states were ending slavery, it expanded mightily in the South. Although only a third of white Southerners owned slaves, many were convinced that slavery was the foundation not just of their economy but of their culture, pride, and identity. And they believed that President Lincoln wanted to force them to abolish it. He had insisted many times in many ways that he had no such intention. Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is, he said in his career-making speech to New York Republicans in 1860. Southerners did not believe him. Through the 1850s they had watched the movement to abolish slavery gain momentum in the North. The movements bible, Harriet Beecher Stowes Uncle Toms Cabin, published in 1852, had sold an astounding two and a half million copies around the world in a single year, convincing Southerners that they were surrounded by enemies. The abolitionist John Browns attempt in 1859 to incite an armed slave rebellion had deeply alarmed them. Though Lincoln and virtually all Northern political leaders had denounced Brown as a mad fool, Northern abolitionists embraced him as a sainted martyr. The more anxious Southerners saw this as a sign that an all-out Northern attack, even military invasion, was imminent.