SHARED DESTINIES... MADE MANIFEST

AT WAR: ABROAD... AND AT HOME

Students at a Mexican School in Texas, 1950s. CREDIT: THE DOLPH BRISCOE CENTER FOR AMERICAN HISTORY, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

TELLING

OUR STORY:

AN INTRODUCTION

THIS STORY is different from other conventional histories you may have read. For an author, recounting a story of one people in a particular place at a particular time is challenging enough, but this book sets out to tell how numerous peoples, from regions and continents flung across the globe, came together to become one people.

The Latino Americans come from Europe, Africa, Asia, and from the ancient nations of this hemisphere. They are the offspring of Spains New World Empire. They arrived in the United States by jet aircraft this morning; they crossed a dusty, empty stretch of desert just yesterday; or long years after arriving here to work, they raised a right hand in front of a federal judge and swore to renounce all other allegiances to any other country. And most important, alongside those whose American story is a recent one are the generations of Latinos whose families have been in this country far longer than there has been a place called the United States, even longer than the arrivals from the British Isles who would go on to invent the United States.

They... we... are all those things at once. We are at once a new people on the American landscape and an old and deeply embedded part of the history of this country and continent. The Spanish names of saints, heroes, captains, and kings dot the landscape of much of the country... all the way from the flowery place, Florida, at the southeast corner, to the San Juan Islands just off the Canadian border in sight of British Columbia. Because restless Americans have steadily moved south and west since World War II, shifting the population away from the Northeast and Great Lakes, millions more Americans unwittingly speak Spanish every day, heading into a Lubys luncheonette in El Paso, the pass, sitting in traffic in San Diego, Saint James, or taking that third card in hopes of hitting twenty-one in that snow-covered place, Nevada.

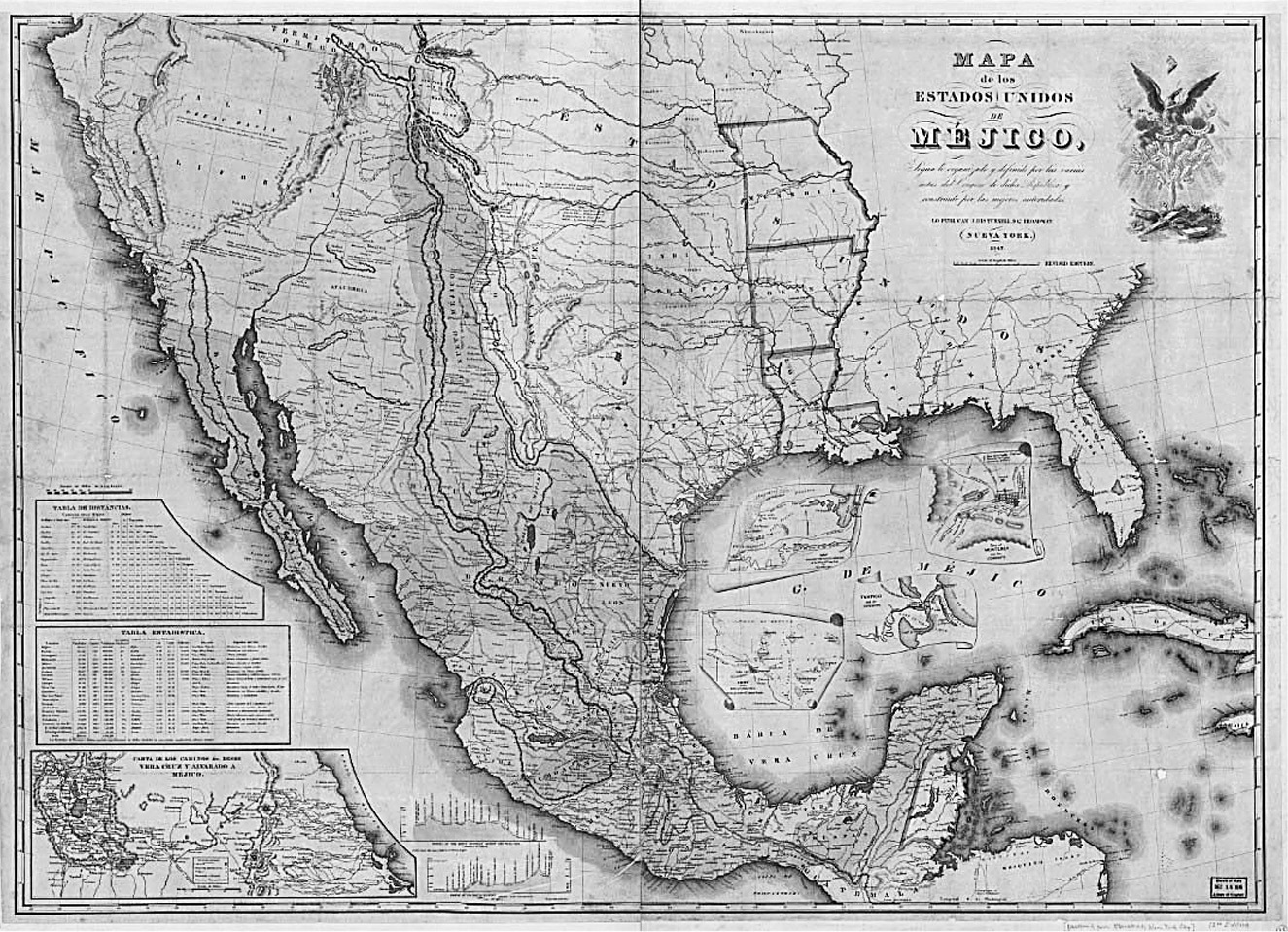

At its height when the nineteenth century began, the Spanish Empire stretched from the islands scattered at the mouth of the Caribbean to the southern tip of South America, up through the Andes and the western Amazon to the continents northern coast, through the slender arm of Central America to the vast landmass of Mexico and into North America, including at various times all or part of the territory of twenty-three U.S. states. The first European language heard in these vast territories was Spanish, the first Christian prayers followed the Roman Catholic rite, and the earliest surveys and land titles were granted to Spanish families.

Mexico in the early years of independence from Spain. This 1837 map shows the vast extent of Mexican territory, including all of what is now the southwestern United States from Louisiana and Arkansas west to the Pacific Ocean. Above what is now California lay the vast Oregon Territory, under joint occupation of the United States and the British Empire during the 1830s. CREDIT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Like the British Empire, the Spanish Empire had a shifting, often cruel and exploitative relationship with the hundreds of nations and peoples already in place when it arrived. Ultimately, however, the history was different in British and Spanish America over long centuries. This is not to minimize or underplay the horrifying tales of genocide, expropriation, and involuntary servitude brought to its enormous empire by the Spanish crown, but only to note that the two stories are different. As the British Empire and its successor governments in the United States pushed Native Americans west from the Atlantic seaboard until there was no more room left to push them into, the descendants of the Maya, Aztecs, and Incas remain very much present in their home countries, fully represented in the gene pool of the people who have come to the United States from the rest of the hemisphere in the last two centuries.

You cannot understand more than fifty million of your fellow Americans without knowing this history. More important, you wont be able to understand the America thats just over the horizon if you dont know this history. Latino history is your history. Latino history is our history.