Copyright 2017 by Purdue University. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available at the Library of Congress.

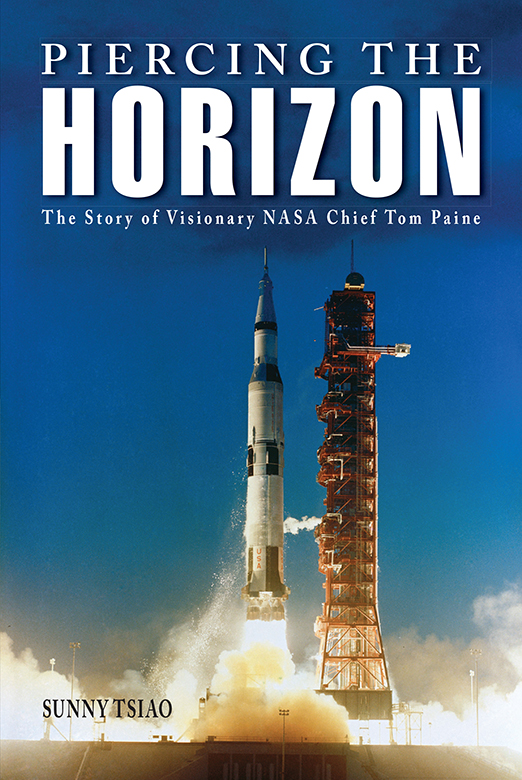

Cover photos courtesy of NASA.

Jacket design by Lindsey Organ.

With the publication of this book, Purdue University Press proudly inaugurates Purdue Studies in Aeronautics and Astronautics, a new family of scholarly books dedicated to the study of flightboth in the atmosphere and in spacein historical, social, technological, political, cultural, and economic contexts.

As readers of the books in our series will learn, the study of aeronautics and astronautics concerns much more than just the nuts and bolts of airplanes and spacecraft. It involves much more than just the history of propellers and wings, more than the history of landing gear and jet engines, more than the ornithology of P-51s and Space Shuttles, or the genealogy of X-planes, rockets, and missiles. The study of aeronautics and astronautics is just as much a story of people and ideas as are studies dealing with any other topic related to society and culture. Without question, scholars who write about aeronautics and astronautics have a lot to say about the research, design, building, flying, maintaining, and utilizing of airplanes, aerospace vehicles, and spacecraft, but their studies are no less human, no less connected to social or political or aesthetic forces, because they deal with technical things. As our books in this new series will demonstrate, an advanced study of aeronautics and astronautics will tell us a great deal about our existence as a thinking, dreaming, planning, aspiring, and playful species.

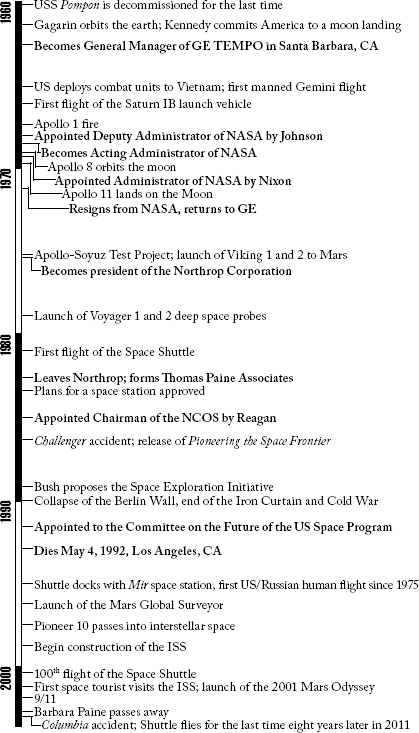

This first book in the new series is a biography of Thomas O. Paine (b. 1921d. 1992), one of Americas greatest spaceflight visionaries. Not only was Dr. Paine the man who headed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration during the period of the United States early manned lunar landings in 1969 and 1970, but he also was deeply involved in preparing plans for the post-Apollo era at NASA. We have many biographies and autobiographies of astronauts and many general, administrative, and technological histories of the US space program, but we have too few critical works on the principal managers and bureaucrats responsible for leading and directing the US space program. Fortunately, we now have a close look at the outstanding career of Thomas Paine. Sunny Tsiao offers a penetrating look into Paines significance as a major figure in the US space program, placing it into the broader context of space history, NASA history, the history of science and technology, American history, and the history of the Space Race.

As with all the publications in our new series, this book should be of interest to a wide group of people, including aerospace scholars, space exploration enthusiasts, those interested in the history of the federal government and federal science and technology planning and management, and the many thousands of people in government, industry, and academe who today are exploring the ways and means of humankinds future in air and space.

JAMES R. HANSEN, PHD

Series Editor

Purdue Studies in Aeronautics and Astronautics

Purdue University Press

PROLOGUE:

MAN WILL CONQUER SPACE SOON

Mission Control Center, Houston, Texas2:15 p.m. Central Time, July 20, 1969

He could see the whole room from where he sat. NASA called it the MOCR, or Mission Operations Control Room, but the rest of the world knew it simply as Houston, a room born of the space age. The nerve center of Americas manned spaceflight program was impressive enough, but was actually quite a bit smaller than it appeared on television. Unless there was a simulation of a spaceflight or an actual mission in progress, Mission Control usually sat empty, with lights dimmed, chairs pushed in under the rows of control consoles, and monitors turned off. Only the whisper of air blowing out of the air-conditioning vents disturbed the silence.

But on this sweltering, humid Sunday afternoon in July 1969, the room was abuzz with pensive excitement. An unmistakable sense of anxiousness, the anticipation of what was about to happen, hung in the air. Mission Control was teeming with flight controllers, mostly young engineers who only three or four years before were studying mathematics and science in college. Now their full attention was on a constant stream of data in the form of numbers and letters that flickered before them on their black-and-white monitors. To the untrained eye, the figures looked like a cryptic alphabet from an obscure, long-lost mathematical language. But to the controllers, the data meant moremuch more. And on this occasion, the telemetry had traveled nearly a quarter of a million miles to reach Houston. It was data that was coming from the moon.

From behind a glass wall separating the VIP viewing area from the floor of the MOCR, Tom Paine focused his attention on a greenish-yellow icon on the large projection screen at the front of the room. It slowly made its way across the screen. Shaped somewhat like the odd-looking Apollo lunar module (LM), it showed the position of the faraway spacecraft as it finally began its long-awaited powered descent to the surface of the moon. The final landing sequence would take only twelve minutes, but NASA had been waiting to make that engine burn for eight years.

Voice transmissions coming over the speakers told him what was happening. The voice signals were surprisingly clear, interrupted only on occasion by some garble and static that one would expect, whether listening to a live broadcast of a baseball game from just down the street or, in this case, two men narrating their own landing onto the surface of the moon. Earlier, Flight Director Gene Kranz, the tough, former Saber Jet pilot who was now directing Mission Controls White Team, had ordered the doors of the MOCR locked. A final status check around the room followed. Each flight controller declared an emphatic GO! into his headset.