For Leigh Hursey Vaccaro, the why and wherefore Im alive. Of all the news joints in all the towns in all the world, she walked into mine. Thank goodness.

I NTRODUCTION

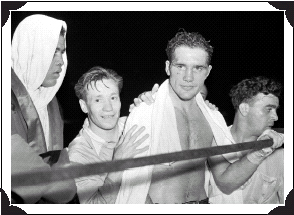

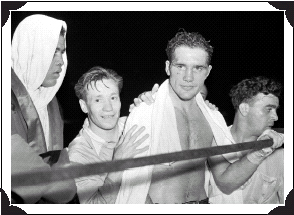

Joe Louis, left, wears his customary dead pan, as he and Billy Conn prepare to leave the ring after their fight at the Polo Grounds June 18. In the center is Johnny Ray, Conns manager.

He was a young man in a hurry in those first weeks of 1941, twenty-three years old, ambitious, obsessed with chasing the American dream in the most American way possible, by playing the blissfully democratic game of baseball.

You could be a regular guy like me, Phil Rizzuto would explain, and you could still make a living at it, if you were good enough, if you worked hard enough.

Rizzuto stood only five feet, five inches tall, weighed but 155 pounds, and hed grown up a Dodgers fan in Ridgewood, Brooklyn. For years hed dreamed of playing in his home borough until the day in 1936 when he showed up at Ebbets Field for a tryout and was crushed by a dour, disapproving Dodgers manager who couldnt believe this runt of a shortstop had dared to fancy himself a would-be, could-be big-leaguer.

Son, the manager said, you can stay and watch the game, but after that youd better run home and get a shoeshine box.

There was a small part of Phil Rizzuto that never forgave Casey Stengel for that dismissal, but a more important piece never forgot it, either. Hunger was a powerful motivator, and even as economic forecasts grew brighter as the 1930s melded into the 1940s, young men everywhere shared a common fuel: the eagerness, the necessity, to find a better place for themselves, and for their families. For Rizzuto, that meant trying to add to the twenty-dollar weekly salary that his father took home each week as a waterfront watchman. For his future teammate with the Yankees, Joe DiMaggio, and a future rival, Ted Williams, it meant evading the erratic prospects of day-work employment in the fishing basins of Northern California and the dull gray warehouses of Southern California. For a truculent pug from Pittsburgh named Billy Conn, it meant fleeing the backbreaking death sentence of forty inevitable years in a steel mill, and for the most famous athlete in the world in 1941, Joe Louis, it meant staying exactly where he was, lest the pull of poverty ever suck him back into the vile vortex from which hed already escaped once.

All you cared about, Rizzuto said, was getting ahead. It was all you thought about.

In 1941, however, the world at large eventually caught up to everyone. It reached Rizzuto on the morning of March 6, when he walked into the Yankee clubhouse and discovered a letter in his locker from Public School 68 back home in Ridgewood, where Draft Board Number 284 was headquartered.

Please advise us, the dispatch began, of the address of the local board nearest your home in St. Petersburg in order that we may send them the order of transfer for physical examination.

Suddenly a curtain had been opened on the world beyond Al Lang Field, the Yankees spring training headquarters. There was no such thing as hiding your head in the sand in 1941, not if you were an able-bodied male, not with the nations first-ever peacetime draft going on, and not with the world seemingly crumbling bit by bit, piece by piece, day by day. This was true for Rizzuto, hoping to earn his first promotion to the big leagues. It was true for Hank Greenberg of the Detroit Tigers, the most decorated and highly paid team sports player in the country, whose two Most Valuable Player trophies and hefty salary helped make him the Alex Rodriguez of his baseball generation, but whose low draft number made him just as vulnerable to military service as a Kansas farmer or a Brooklyn apprentice plumber or an aspiring California actor.

The morning papers didnt simply report the news in 1941, they screamed it, and whatever they missed the afternoon papers shouted even louder a few hours later. The same day Rizzuto received his letter, the dailies were stuffed with stories speculating about Yugoslavias immediate future. Hitlers army had encircled it, and it seemed the country was only hours away from capitulating, one more trophy for the Fuehrers mantel. Every day brought something new, something worse, something unspeakable.

You read the sports section a lot, Rizzuto would say years later, because you were afraid of what youd see in the other parts of the paper.

To appreciate how much sports meant in 1941, you must first understand what its landscape looked like. Basketball was a minor-league curiosity, its professionals confined to barnstorming tours and chilly armories, many of its games still contested behind chicken-wire netting, earning its practitioners the derisive nickname of cagers. Football was king on college campuses, but since the majority of Americans in 1941 had never set foot in a university lecture hall, it was a pastime that thrived detached from most of the nations urban centers. And pro football was still a nascent phenomenon, played before sporadic pockets of fans, still searching for its niche just fifteen years after boasting such hub cities as Racine, Hammond, and Duluth as members. It didnt pay very well; for much of 1941, Tommy Harmon, whod won the 1940 Heisman Trophy at Michigan, insisted he wasnt going to play pro ball, opting instead for a more lucrative radio gig in Detroit. Auto racing was mostly a once-a-year carnival act contained at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The National Hockey League existed in only four U.S. cities. Golf was a pastime mostly pursued by the fortunate segment of well-to-do citizens who hadnt been decimated by the Depression.

No, in 1941, only three sports truly mattered in the American consciousness. There was baseball, the undisputed king, the game still favored by an overwhelming number of children, one that filled every sandlot and every playground in one incarnation or another. There was boxing, dominated in 1941 by Joe Louis, entering his fourth year as the undisputed heavyweight champion, an African American whose appeal crossed racial and cultural boundaries of every kindno small feat in a nation where Jim Crow laws dominated the lower half of its geography, where a gentlemans agreement barring men of color from organized baseball still thrived, where even in the army races werent yet mixed. And there was horse racing, the self-styled sport of kings, which offered Americans almost everything they could have desired in 1941: wide-open outdoor spaces, cheap admission prices, and the opportunity to leave with their pockets a little fuller than when theyd arrived, thanks to the recent advent of pari-mutuel betting.

People embraced all sports that year in ways they never had before. In March the National Invitation Tournament drew 70,825 college basketball fans over four nights at Madison Square Garden, easily a record. New attendance records were broken at the Kentucky Derby and at the Indianapolis 500. Boxing nights in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., St. Louis, Denver, and Baltimore all drew record single-night crowds. In the spring, over 155,000 people flocked to St. Paul, Minnesota, to watch the American Bowling Congress tournament. A brash young Californian named Bobby Riggs electrified Forest Hills by winning the U.S. Open, the only one of tenniss four Grand Slam events held in 1941 because of more strident matters occupying the sites of Wimbledon, the French Open, and the Australian Open. Even though tennis was still mostly a country-club game, unprecedented crowds made their way to the West Side Tennis Club.