Contents

Guide

Portable Press

An imprint of Printers Row Publishing Group

10350 Barnes Canyon Road, Suite 100, San Diego, CA 92121

Copyright 2019 Welbeck Non-fiction Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Printers Row Publishing Group is a division of Readerlink Distribution Services, LLC.

Portable Press is a registered trademark of Readerlink Distribution Services, LLC.

Correspondence regarding the content of this book should be addressed to Portable Press, Editorial Department, at the above address. Author and illustration inquiries should be addressed to Welbeck Publishing Group, 2022 Mortimer St, London W1T 3JW.

Portable Press

Publisher: Peter Norton

Associate Publisher: Ana Parker

Publishing/Editorial Team: April Farr, Kelly Larsen, Kathryn C. Dalby

Editorial Team: JoAnn Padgett, Melinda Allman, Traci Douglas

Produced by Welbeck Non-fiction Limited

eBook ISBN: 978-1-64517-272-7

eBook Edition: October 2020

All illustrations provided by Noun Project with the exception of Eddo via Wikimedia Commons

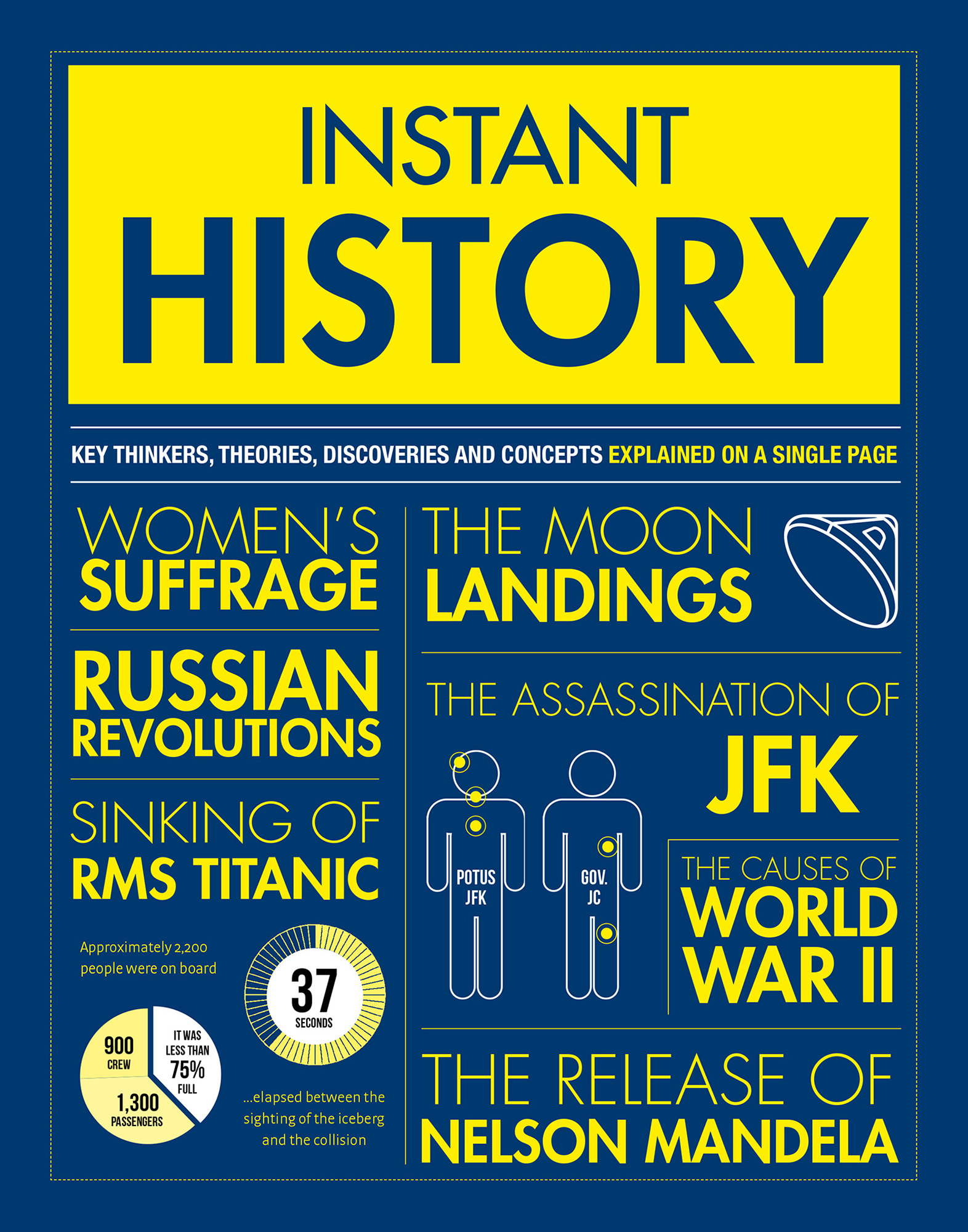

INTRODUCTION

History never stands alone. Its rarely even a chain of events. If anything, it is more like a web of causes and effects, often stretching back centuries to seemingly unconnected matters. The only way to see the whole picture is to stand back, look at what happened whereand work out the connections.

The Age of Discovery, for example, is a broad subject that opens this book, seemingly at random. The desire to explore was the consequence of many already-simmering human urges. Some merely wanted to know whatif anythingwas on the other side of the known seas, to fill in the blank spaces in their charts currently inhabited by imaginary monsters. Perhaps there would be treasure, spices, minerals, foods, or ideas. Europes population was growing; extra land would be useful. Many wanted to trade, some to settle. A few to conquer.

As new lands, nations, and commodities were discovered, an era of transcontinental trade began, introducing Europe to exotic items from strange vegetables to gunpowder. The printing press helped spread news and ideas. The Renaissance saw staggering works of art and magnificent buildings, constructed with imported materials and funded by new-found wealth. Powerful private companies plied the seas, trading in luxuries, commoditiesand people. They were helped by scientific advances in shipbuilding and weaponry, hindered by a growing underbelly of piracy, often state sponsored. In the race to colonize new-found continents, European nations fought each other in every way they knew.

Civilizations in the Middle East and Far East had webs of their own: for every Sistine Chapel there was a Forbidden City. The Aztec Empire flourished for centuries before the Spanish arrived, but these worlds collided, and new webs began.

As colonists carved continents between themselves, their religions were imposed on the conquered peoples. The Catholic Church, especially, grew ever more powerful. It resisted others, from the Moors of Africa to breakaways from its own faith, like Henry VIIIs Church of England. It mistrusted those it had forcibly converted, such as the Jewish conversos, instigating the Spanish Inquisition to root out rotten souls from the old world and new. It didnt go unchallenged; a new interpretation of Christianity was beginning to defy the established Church. Puritans and other religious separatists joined the exodus of European explorers, traders and invaders seeking a new life in the American colonies, even as European ambassadors were sent to the great courts of the Mughal and Ottoman empires.

The ambassadors had less success further east. Fundamental misunderstandings between cultures saw trade with self-sufficient China severely limited and nonexistent with Shogun-ruled Japan. Some continents were still easy pickings. Australia, newly discovered by Captain Cook, provided an excellent dumping ground for convicted British criminals. Slavery still powered Europes plantations, bringing the kind of wealth that built palaces, landscaped gardens, and fueled vast industrial cities back home.

Europes colonies were maturing. Their people began to realize that, rather than being treated equally with the citizens of their ruling nations, they were being used as wealth generators. Inspired by ideas thrown up by the Enlightenment, and encouraged by civil war in England and, later, revolution in France, one by one they began to demand autonomy, starting in what would become the United States of America.

Freedom for some saw a new yearning for freedom for all. Slavery still blighted most of the Americas and elsewhere. The fight for abolition would take generations and, in the United States, a civil war. Without the industrial revolution, the fight would have been even bloodier. Plantation owners were able, at least in part, to replace forced manual work with machinery. In the mills back home, the working classes were able to produce more in the cities and factories than they had ever managed in the rural world. Railroads transported goods across land and steam ships across the seas, returning with exotic goods from around the world, for those that could afford them. Those who could not were increasingly attracted to new philosophies such as those of Karl Marx, advocating a new kind of world order: communism. Half the populationwomenbegan demanding something more fundamental: the right to vote.

Inventions came thick and fastthe motor car, the light bulb, powered flight. All would have a profound effect on the ever-more complicated twentieth-century web. Flight, for example, allowed millions to experience the world and enabled the transportation of goods, people, and news. It also changed the face of warfare, from zeppelins to atom bombs to 9/11. Two world wars managed to encompass countries half a world from their original sources, often compounding new disagreements with old, festering wounds from a century or more before. Returning soldiers brought home Spanish Flu, a pandemic of a voracity not seen since the Black Death, yet hope also arrived in the form of new medications, discoveries, and innovations. Even as the world descended into a second devastating war, records for human achievement were broken at the Olympic Games, to be constantly improved upon through the rest of the century as humans conquered the highest mountains and deepest oceans.

Small webs grew to large ones. The assassination of one figure could topple many, as in the case of Archduke Ferdinand. With Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, it focused the Civil Rights Movement to new purpose, while a by-product of the assassination of John F. Kennedy put a man on the Moon.

This book cannot begin to encompass every event in history. Even with the moments profiled here, a couple of hundred words do not even scratch the surface of extremely complex subjects. All it can hope to do is show, in easily digestible bullet points, a few of the millions of threads that make up the web of the world. Each entry highlights salient points worth following up later, with an eye to seeing the bigger picture. As patterns emerge and connections build, historys causes and effects become clearer. Understanding what brought us Spanish Flu, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or the Watergate Scandal is at least part way to knowing how to prevent new versions of old evils.