Preface

The Story Behind the Masterpiece

As for my maps, I have heard people say that illustrative maps have been made for a long time. My maps do not just show, they also count, they calculate for the eye; that is the crucial point, the amendment I have introduced through the width of the zones in my figurative maps and through the rectangles in my graphic tableaus.

CHARLES-JOSEPH MINARD, 1861

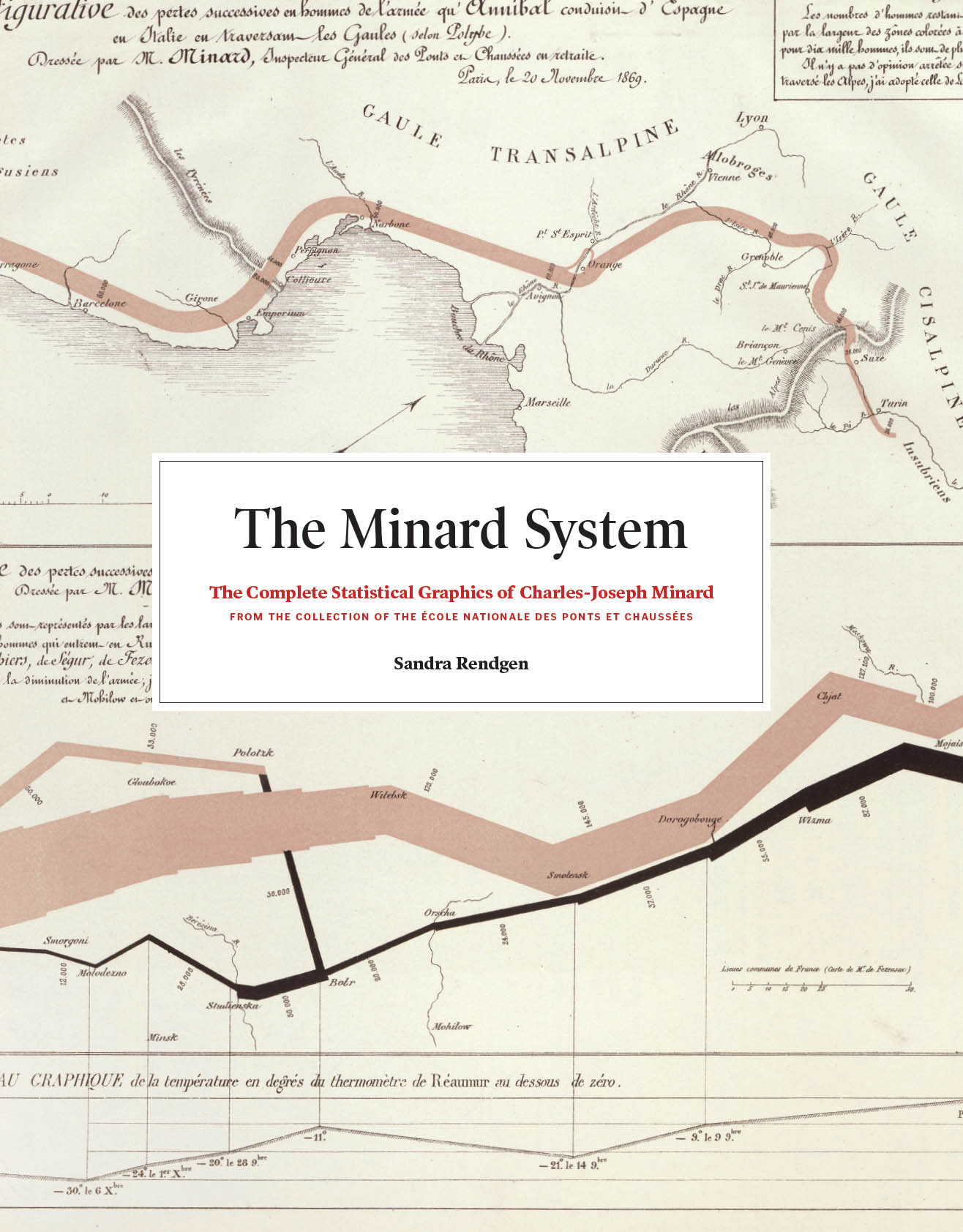

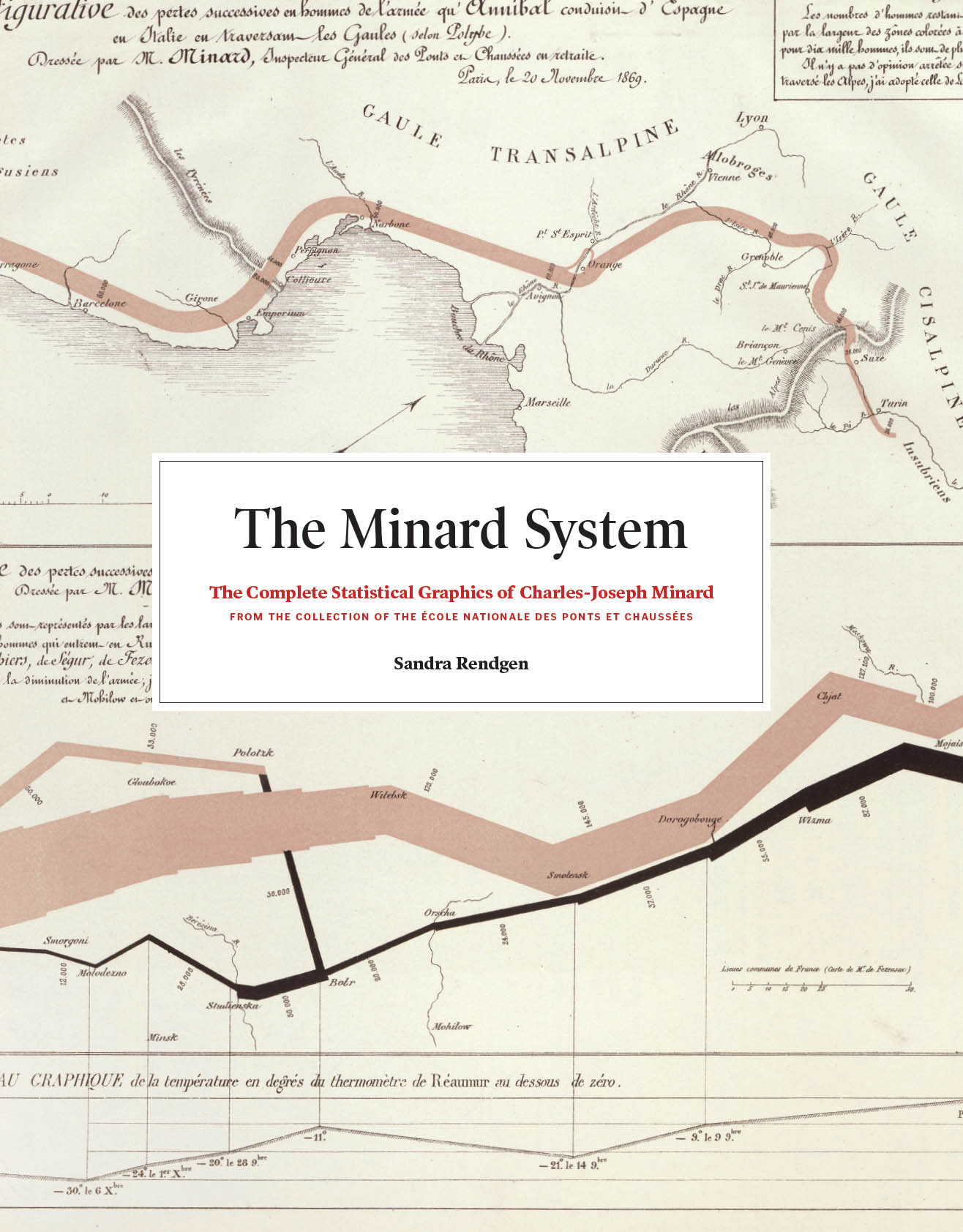

The French civil engineer Charles-Joseph Minard, whose long life spanned the final years before the French Revolution through the latter half of the nineteenth century, left behind an impressive body of statistical graphics and maps. Motivated by the intellectual problems he encountered during his professional practice, Minard embarked on a quest to create compelling visualizations to support the analysis of statistical results. He conducted in-depth studies over many decades, and his efforts finally led him to create one of the most famous information graphics ever made: a statistical map of Napolons Russian campaign of 1812.

Published in 1869, one year before Minards death, this graphic eloquently summarizes Napolons disastrous military endeavor. On a basemap of what are now Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Russian territories, it visualizes one particularly telling statistical variable: the sharp and steady loss of soldiers that Napolons army suffered during the roughly six months covered in the graphic. Though 420,000 men triumphantly invaded Russia in June 1812, the army was already significantly reduced by the time it arrived in Moscow three months later. When Napolon ordered the troops to retreat from Moscow in the fall, he sent his men to certain death, as they faced an extremely harsh winter in the wide plains of western Russia without any support or infrastructure. The map shows that only some ten thousand soldiers survived .

This work has stood out from Minards extensive oeuvre for a long time and continues to do so today. Its fame has even produced some curious mementos, such as a T-shirt featuring the Napolon flow (currently available, along with other Minard-related merchandise, in several online shops). Tufte, through his groundbreaking books on the principles of designing statistical graphics, can be credited with having brought the work of Minard to the attention of a wider contemporary audience.

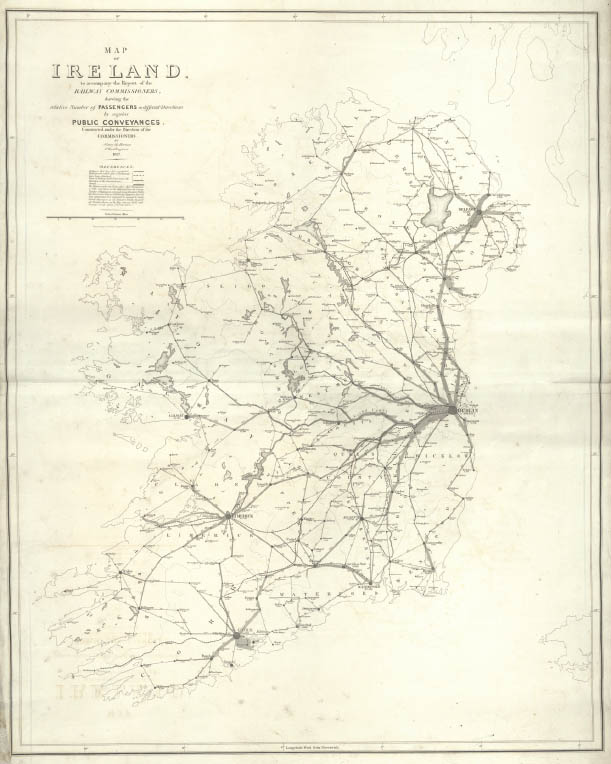

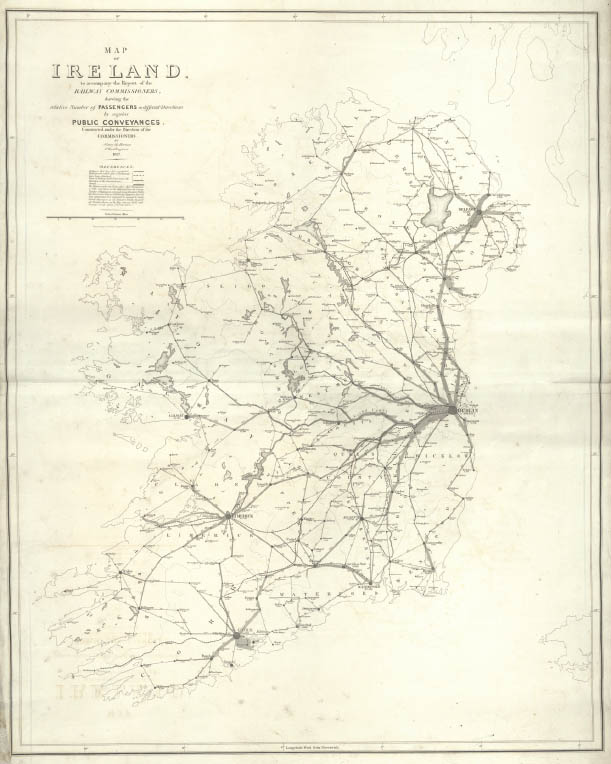

The Royal engineer Lieutenant Henry Drury Harness drew this map in 1837 as part of an atlas to accompany a report by the Irish Railway Commissioners. It is considered to be the first flow map and preceded Minards work by a few years. However, there is no sign that the latter had any knowledge of this atlas.

Tufte was by no means the first author to ardently praise Minards work. As early as 1878, the French scientist tienne-Jules Marey reproduced the Napolon map in his comprehensive compendium, La mthode graphique dans les sciences exprimentales et particulirement en physiologie et en mdecine (The graphic method in the experimental sciences and particularly physiology and medicine). He also recognized the immediate visual power of this work, celebrating it with the much quoted remark about its brutal eloquence, which seems to defy the pen of the historian. Unfortunately, despite these historians groundbreaking work, many of Minards maps have remained unknown to the broader public; all the while, general interest in the history of thematic mapping and statistical graphics has grown exponentially following the surge in information visualization since the 1990s.

It is no coincidence that we should take a renewed interest in Minards impressive body of work. There are several powerful forces shaping his oeuvre that resonate in our contemporary culture. One of these is an unprecedented abundance of data. The early nineteenth century saw the rise and establishment of the new science of statistics, and Minard, as well as many of his contemporaries, viewed it as a fertile source of information and began to work with this data. Though statistics is now a well-established scientific field, we too are experiencing an unprecedented abundance of structured data, brought about by the rise of digital technologyand it is no coincidence that visualization research has seen a massive rise over the past decades.

Another factor that shaped Minards oeuvre was the profound change that new communication and transit technologiessuch as steam locomotion, the railroad, and the telegraphbrought to the nineteenth century. We also find ourselves in the middle of a technological revolution, which has led to an urgent need to discuss, reflect, and understand the machines that pervade ever more aspects of our lives and create an atmosphere of unprecedented complexity. Minard worked within a sphere of well-educated people who embraced the challenge of grappling with the new developments. He was a pioneer in a movement that aspired to make statistical data useful in the face of monumental cultural changes, and he contributed more works to the emerging field of information visualization than any other single person in the nineteenth century.

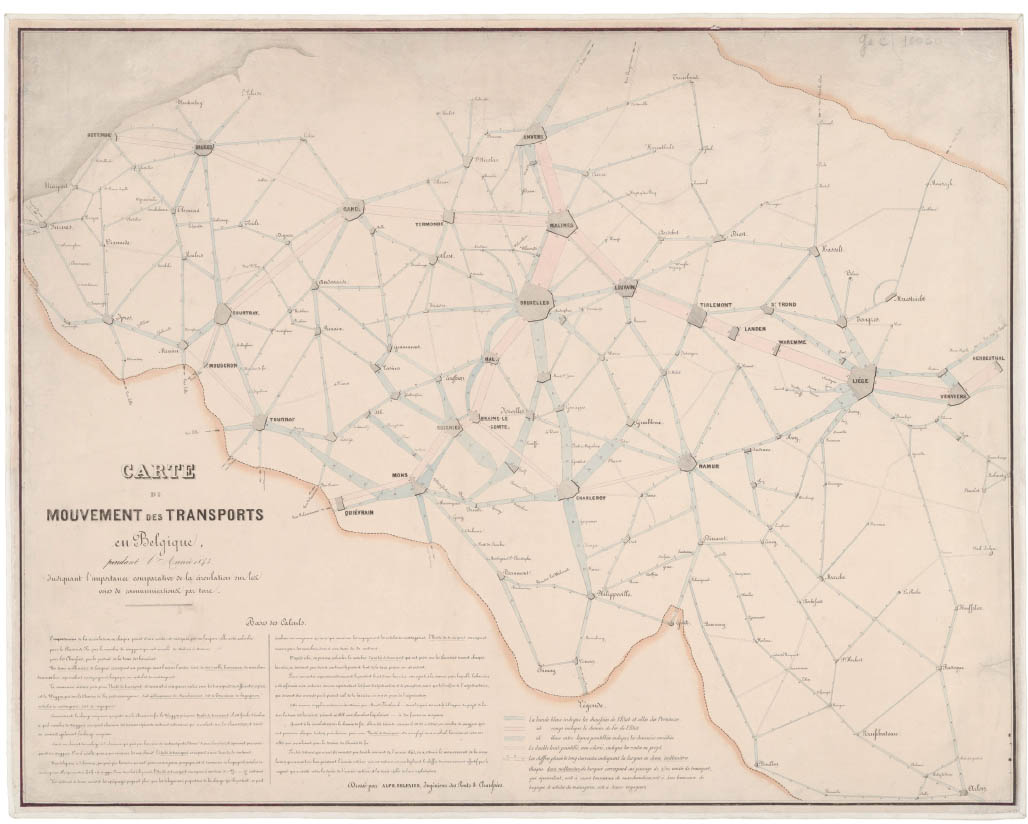

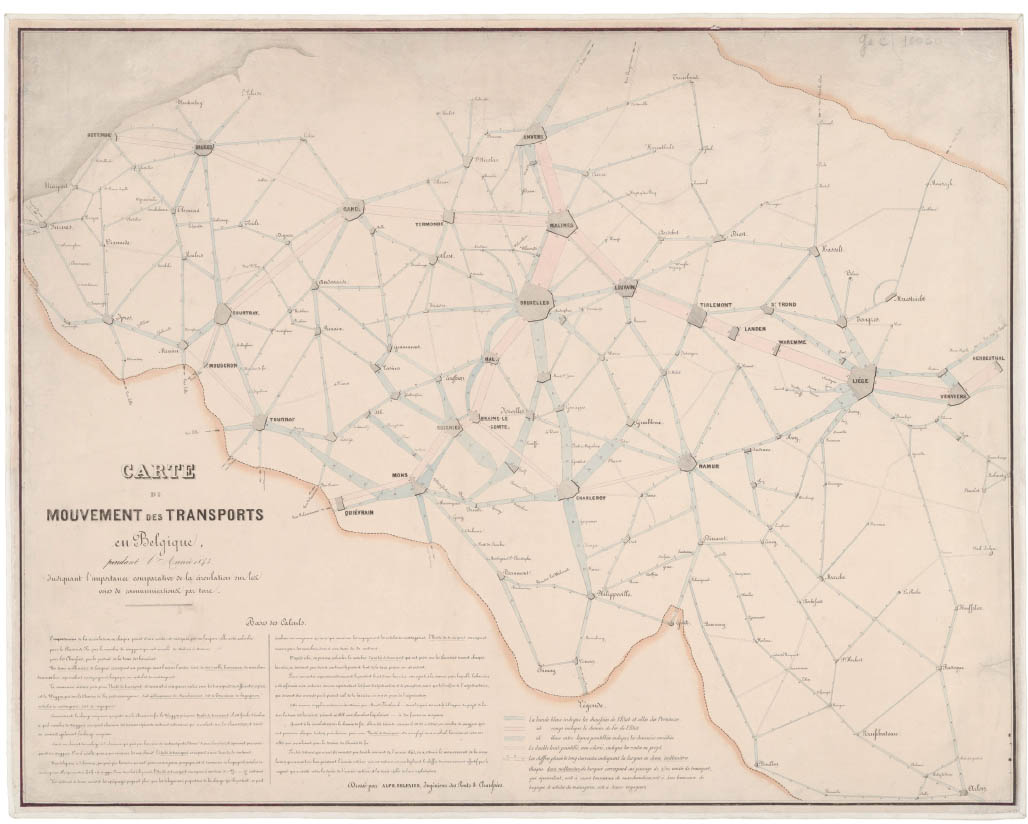

Independently and parallel to Minard, the engineer Alphonse Belpaire created a flow map on traffic in Belgium over the year 1843. The map does not bear a date, but it is likely to have been published in 1845. Blue bands refer to roads, rose bands to railroad lines. The flow width shows quantities of transport, such that a half millimeter represents either 10,000 tonnes of goods, 5,000 tonnes of baggage, or 30,000 travelers.

Although he worked with various methods, Minard is particularly associated with the development of the flow map. Regardless of these instances, the flow method can be considered Minards major theme in and contribution to information visualization, with forty-one such maps in large-format by his hand alone.

This book will explore the following questions: What is the Minard system? What prompted Minard to develop this method? What lucky coincidences were involved in creating such a large body of work? What obstacles did he encounter in visualizing data in this manner? And when and why did he resort to other visualization methods? The introductory essay highlights the major influences that shaped Minards intellectual life and set the stage for his oeuvre of statistical graphics. The catalog presents a complete collection of Minards statistical graphics as well as detailed documentation of his technical drawings. This book thus creates an integrated view that will allow for a thorough account of Minards studies in statistical visualization, and that aims to make the conditions and results of his efforts known to a larger public.

Introduction

The Minard System: A Geography of Flux

Life and Career

Charles-Joseph Minard was born in 1781 to a middle-class family in Dijon, France, where he was educated at the local college. He showed a preference for mathematics and physical sciences early, and, at the age of fifteen, he entered the recently founded cole polytechnique in Paris, where he studied from 1796 to 1800. He was subsequently admitted to the prestigious cole des ponts et chausses in Paris to pursue a degree in civil engineering (ca. 180003). To this day, this school is the training center for the renowned state-run Corps des ponts et chausses (now a part of the Corps des ponts des eaux et des forts), a national body of expert engineers tasked with overseeing the French traffic infrastructure. All through his professional career, Minard remained closely associated with both the cole and the Corps; the cole archive continues to maintain the complete collection of Minards works. After graduating from the cole des ponts et chausses, Minard pursued a long and successful career that took him from civil engineer, to inspector, to member of the Corps. In 1822, at the age of forty-one, he married the daughter of a college friend from Dijon. The couple had two daughters who grew to adulthood; one son was lost in early infancy.

Next page