Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

A History of Data Visualization and Graphic Communication

Michael Friendly

Howard Wainer

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England2021

Copyright 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover art: Detail of Playfairs Chart of Universal Commercial History. Source: William Playfair, An Inquiry into the Permanent Causes of the Decline and Fall of Powerful and Wealthy Nations Designed to Shew How the Prosperity of the British Empire May Be Prolonged. London: Greenland and Norris, 1805.

978-0-674-97523-1 (hardcover)

978-0-674-25904-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25903-4 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Friendly, Michael, author. | Wainer, Howard, author.

Title: A history of data visualization and graphic communication / Michael

Friendly, Howard Wainer.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020047837

Subjects: LCSH: Information visualizationHistory. | Visual

communicationHistory. | Graphic methodsHistory. | Visual

analyticsHistory.

Classification: LCC QA76.9.I52 F74 2021 | DDC 001.4/226dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020047837

To Martha,

Abigail and Gustavo, Ethan,

Luca and Oliver

To Linda,

Sam,

Laurent, Lyn, Koa and Sophie

Contents

The only new thing in the world is the history you dont know.

HARRY S. TRUMAN, quoted by David McCulloch

We live on islands surrounded by seas of data. Some call it big data. In these seas live various species of observable phenomena. Ideas, hypotheses, explanations, and graphics also roam in the seas of data and can clarify the waters or allow unsupported species to die. These creatures thrive on visual explanation and scientific proof. Over time new varieties of graphical species arise, prompted by new problems and inner visions of the fishers in the seas of data.

Whether were aware of this or not, data are a part of almost every area of our lives. As individuals, fitness trackers and blood sugar meters let us monitor our health. Online bank dashboards let us view our spending patterns and track financial goals. As members of society, we read stories of outbreaks of wildfires in California or extreme weather events and wonder if these are mere anomalies or conclusive evidence for climate change. A 2018 study claimed that even one alcoholic drink a day increased health risks,

These illustrations are really about understanding something systematic or the strength of evidence for a claim. How much does my blood sugar go up if I skip my morning run or eat a Krispy Kreme donut? Are there really more wildfires in California or more extreme weather events worldwide in recent years? Exactly how much does my health risk increase from drinking one or two glasses of wine a day, as others had long recommended, compared with total abstinence?

For such questions, evidence can be presented in words, numbers, or pictures, and we can try to use these to evaluate the strength of a claim or argument. The purpose of scientific research is to gather information on a topic, turn that into some standard form that we can consider as evidence, and reason to a conclusion or explanation. A graph is often the most powerful means to accomplish this because it provides a visual framework for the facts being presented. It can answer the important, though often implicit, question, compared to what? It can convey a sense of uncertainty of evidence for the validity of a claim. Yet it also enabled viewers to think more deeply about the question raised and challenge the conclusion. A diagram can provide a visual answer to a problem and graphic displays can communicate and persuade.

As we illustrate in this book, graphs and diagrams have often played an important role in understanding complex phenomena and discovery of laws and explanations. To truly understand the impact of a visual framework, we must not only look at contemporary examples, we must also learn how it changed science and society. We must learn history.

A Long History

This book recounts a long history, a broad overview of how, where, and why the methods of data visualization, so common today, were conceived and developed. You can think of it as a guided tour of this history, focusing on social and scientific questions and a developing language of graphics that provided insights, for both discovery and communication.

This book has a long personal history as well. It began in October 1962, when we met as undergraduates at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Sequentially we became math majors, house mates, and friends. We then did our graduate work at the same university (Princeton), both supported by Educational Testing Services Psychometric Fellowship. There we came into contact with John Tukey, Princetons widely celebrated polymath, who was in the process of revolutionizing the field of statistics with the idea that the purpose of data analysis was insight, not just numbers, and that insightseeing the unexpectedmore often came from drawing pictures than from proving theorems or deriving equations.

Tukeys guidance proved important and prophetic as we found that whatever substantive topic we worked on, our ability to understand and communicate the evidence we gathered almost always involved viewing the data in some graphic format. Our research led us both to gravitate toward aspects of the use and development of data visualization methods. This interest spanned their applications in scientific exploration, explanation, communication, and reasoning, as well as the creation of new methods for illuminating problems so that they can be understood better.

Remarkably, for both of us, our studies of graphical methods took us back ceaselessly into the past for a deeper and more thorough understanding. Much of what seemed commonplace today turned out to have deep historical roots.

There is also a long history of research, collaboration, and writing that informed this book and prompted this account. One initial foray was the 1976 National Science Foundation Graphic Social Reporting Project directed by Wainer.

One of the projects tasks was to assemble a coherent group of international scholars who worked on the use of graphics to communicate quantitative phenomena and create a social network to facilitate the sharing of information. This led to several conferences, a fair number of scholarly articles (e.g., Beniger & Robyns 1978 history of graphics, Data visualization, as a field of study, was off to the races.

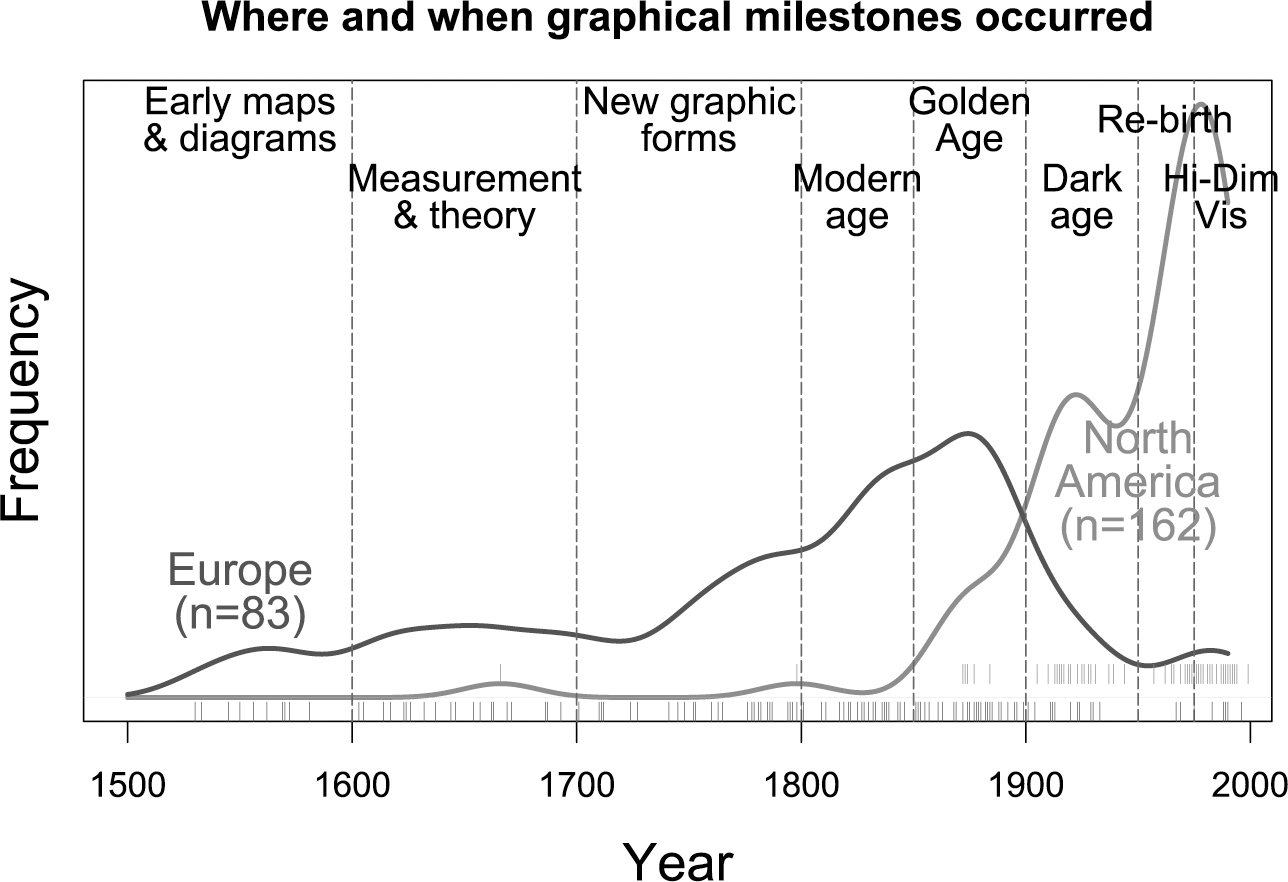

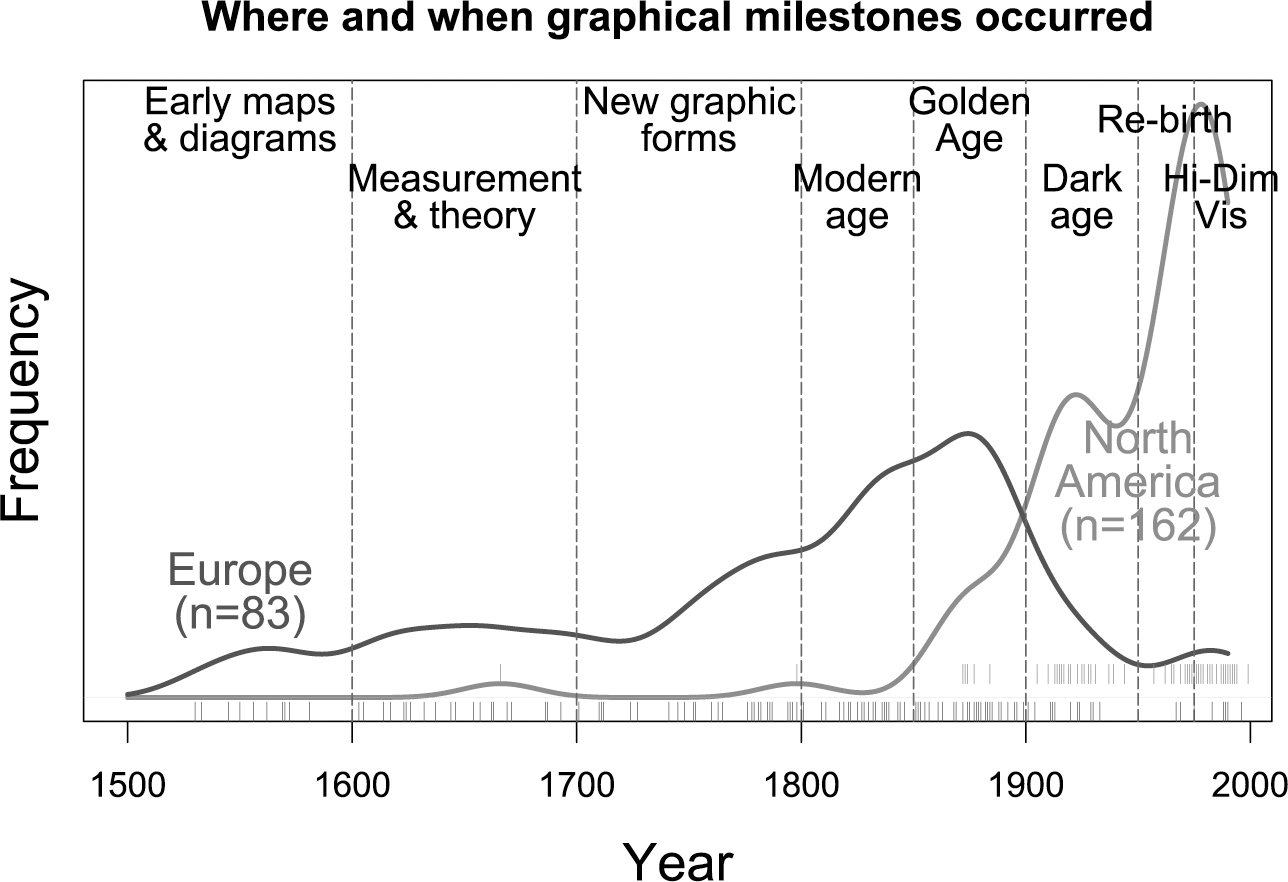

A second key event was Friendlys Milestones Project. The Milestones Project began simply as an attempt to collate these diverse contributions into a single, comprehensive listing, organized chronologically, that contained representative images, references to original sources, and links to further discussiona source for one-stop shopping on the history of data visualization. It now consists of an interactive, zoomable timeline of nearly 300 significant milestone events, nearly 400 images, and 350 references to original sources, together with a Google map of authors and a milestones calendar of births, deaths, and important events in this history.