Has Archaeology Buried the Bible?

William G. Dever

WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY

GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

4035 Park East Court SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

www.eerdmans.com

2020 William G. Dever

All rights reserved

Published 2020

262524232221201234567

ISBN 978-0-8028-7763-5

eISBN 978-1-4674-5949-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dever, William G., author.

Title: Has archaeology buried the Bible? / William G. Dever.

Description: Grand Rapids, Michigan : William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: A reevaluation of biblical historicity, truth, and morality based on recent archaeological findingsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019060216 | ISBN 9780802877635 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Old TestamentAntiquities. | Bible. Old TestamentEvidences, authority, etc. | PalestineAntiquities. | Middle EastAntiquities.

Classification: LCC BS621 .D485 2020 | DDC 220.9/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019060216

Contents

This book has been in the making for more than sixty years, since I was a young graduate student. I had been raised in the manseone of a fundamentalist stanceand by that time I was myself a cleric while a student in a liberal seminary. Already I felt keenly the challenge of reading the Bibleespecially the Christian Old Testamentintelligently, critically, yet in a way that did not compromise what I thought of as its enduring religious values.

I wrote an MA thesis on Old Testament Theology, then in vogue. I went on to a PhD program at Harvard to pursue that interest with G. Ernest Wright, at the time one of Americas leading Old Testament scholars and our most prominent biblical archaeologist. Archaeology soon won out over theology, and I began an archaeological career with Wright at biblical Shechem (Tell Balaah ) in 1962. I never looked back. But I also never forgot my original aim: to help make the Bible more meaningful to modern readers. Now, however, I had a new pulpit, and perhaps in time a new gospel.

I have written numerous articles and books, most of them technical scholarly works on archaeology, some on biblical studies, all works for a rather small audience. This book, however, is meant to be different: truly popular, nontechnical, and unencumbered by copious footnotes and vast bibliography. It intends to simplify complex issues and take a commonsense, middle-of-the-road approach. Even though I have been a participant in nearly all the inevitable archaeological controversies over the years, I try to make the discussions here accessible and balanced, so I write in the third person.

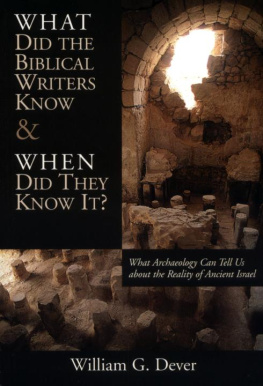

Those who wish to pursue the issues treated of necessity rather simply here will find all the details and references to the vast literature in my Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah (SBL Press, 2017). The list of Suggested Readings at the end of the book may also be helpful; it cites the best accessible and readable sources.

Some believers may think that I undermine the Bible, while secularists may say that there is no point in trying to save the Bible. I am doing neither. I only suggest a middle ground, an up-to-date but modestly optimistic approach to the Bible. Others may find this book moralistic; but the fundamental, universal issues are always moral. And the Bible, along with other great literature, remains a good guide.

I have become indebted to too many along the way to credit them all here: parents, teachers, family, students, and colleagues. My wife Pamela Gaber has listened to many trial readings and has offered improvements that I would not have thought of. An anonymous supporter and benefactor offered encouragement so strong that I had to write this book.

On a few technical matters, BCE and CE are used instead of BC and AD, in keeping with the most current usage. I use the Hebrew word Yahweh for God, since that is most often the actual term in the Hebrew Bible, not Lord, as many translations have. Yahweh is the proper name of the national deity of Israel, best understood as the causative form of the Hebrew verb hyh, to be, thus He who causes to be, that is, the creator.

Translations from Hebrew may follow any one of several versions, and readers can compare on their own. Sometimes I provide my own translation or paraphrase. In all cases I try to convey the best meaning of the biblical text.

The land of ancient Israel is not called Palestine, since that term came into use only later, in the Roman period, and in any case it is compromised by the current political situation in the Middle East. Levant is the more neutral geographical term, meaning modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, the West Bank, and Israel. Southern Levant includes the latter three. Canaanite is usually clear from the context. Late Bronze Age means the time period of circa 15001200 BCE; Iron Age from circa 1200600 BCE.

I may use Arabic names for many biblical sites, usually large tells or mounds, because in some cases that is all we have, the ancient names having been lost.

The word cult is not derogatory but simply refers to religious practices, which is what archaeology illuminates best. I dont deal with theology directly, ancient or modern. I leave that to specialists, clerics, and others. Here I have no theological axe to grind. I also do not raise technical questions about the authorship or the structure of the biblical texts. That, too, is for specialists. But the text as it stands now is all we have to work with.

What concerns us here is not the question of who wrote the text or where or when, but rather what does it say, read in a straightforward way? In short, what did the biblical authors and editors think they were describing, and what did they mean? Then and only then will we proceed to a critical evaluation of the texts, using archaeology as a primary source. Thus, we can compare what the texts did mean, and what they may still mean.

Finally, biblical chronology is complex, so the dates here are those used by mainstream commentaries. Unless specified otherwise, they are all BCE. The word Bible always means the Hebrew Bible, often mistakenly called the Old Testament by Christians. Properly speaking, it is the Bible of ancient Israel and the Jewish community, today not old at all, but still current.

The Holy Landa fascinating, centuries-old conceptwas about to take on new life when archaeological work began in the mid-nineteenth century in what was then called Palestine (modern Israel and the Palestinian territories), at the time part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Archaeologists had already begun making spectacular discoveries elsewhere in the Middle East, in Egypt and Mesopotamia, some promising to shed astonishing light on the Bible.

The first investigation of one ancient site in Palestine, however, came only in 1863, when Flicien de Saulcy claimed to have found the rock-cut tombs of the kings of ancient Israel (though they turned out to be nothing of the sort).

As actual excavations began in Palestine, and in Transjordan and Syria as well, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the overriding goal continued to be to illuminate the long-lost world of the Bible. Thus, places chosen for excavation were typically sites known from the Old and New Testaments: Samaria, Megiddo, Jericho, and of course Jerusalem. The sponsoring societies were quite candid about their objectives. As the British Palestine Exploration Fund described itself in their initial statement in 1865: