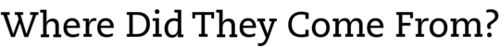

Who Were the Early Israelites

and Where Did They Come From?

Who Were the Early Israelites

and Where Did They Come From?

William G. Dever

In loving memory of my son Sean William Dever 1969-2001

Contents

ix

Introduction

For nearly two thousand years the so-called Western cultural tradition has traced its origins back to ancient Israel. In Israels claims to have experienced in its own history revealed truth of a higher, universal, and eternal order, we in Europe and much of the New World have seen a metaphor for our own situation. We considered ourselves the New Israel, particularly we in America. And for that reason we knew who we were, what we believed in and valued, and what our manifest destiny was.

But what if ancient Israel was invented by Jews living much later, and the biblical literature is therefore nothing but pious propaganda? If that is the case, as some revisionist historians now loudly proclaim, then there was no ancient Israel. There was no actual historical experience of any real people in a real time and place from whom we could hope to learn anything historically true, much less anything morally or ethically enduring. The story of Israel in the Hebrew Bible would have to be considered a monstrous literary hoax, one that has cruelly deceived countless millions of people until its recent exposure by a few courageous scholars. And now, at last, thanks to these social revolutionaries, we sophisticated modern secularists can be liberated from the biblical myths, free to venture into a Brave New World unencumbered by the biblical baggage with which we grew up. Our gurus will be those renegade biblical scholars - along with the new historians, anti-humanists, and cultural relativists whom the historian Keith Windschuttle has described so well in his devastating critique The Killing of History: How Literary Critics and Social Theorists Are Murdering Our Past (1996).

Anyone who is uninspired by this vision of a postmodern utopia, who wishes to salvage something of the biblical story of ancient Israel and its value for our cultural traditions, will have to begin at the beginning with the biblical accounts of Israels origins in Egypt and Canaan, the socalled Exodus and Conquest. But are these dramatic, memorable stories historical at all in the modern sense? Where might we turn for external, corroborative (or corrective) evidence? And finally, why should the biblical narratives about ancient Israel, factual or fanciful, matter to anyone any longer?

It is to these questions that this book is addressed.

A word about methodology may be helpful, with particular reference to my task here - that of using archaeological evidence as a control (not proof) in rereading the biblical texts. I would argue that there are at least five basic approaches to doing so, in a continuum from the right to the left. One can

I. Assume that the biblical text is literally true, and ignore all external evidence as irrelevant.

2. Hold that the biblical text is probably true, but seek external corroboration.

3. Approach the text, as well as the external data, with no preconceptions. Single out the convergences of the two lines of evidence, and remain skeptical about the rest.

4. Contend that nothing in the biblical text is true, unless proven by external data.

5. Reject the text and any other data, since the Bible cannot be true.

In the following, I shall resolutely hold to the middle ground - that is, to Approach 3 - because I think that truth is most likely to be found there.

I should acknowledge that in my attempt to tell the story of early Israel and to make it accessible to the average educated reader, I have indulged in some oversimplifications. This has been necessary, but nevertheless I have tried to give a balanced account of the data and an honest account of the views of other scholars. The reader will find more details in the works cited at the end of the book. As for my own biases, they will be clear enough.

Since I approach this topic as an archaeologist and historian, not a literary critic of the Hebrew Bible, I have not discussed the numerous works that deal simply with the relevant texts as literature. Most of these works, oddly enough, including those both to the left and to the right, eschew the problem of actual historical reconstruction. Such works tend to be a history of the literature about the history of ancient Israel, whereas I focus more on what Albright termed the realia.

Finally, by way of introduction, when referring to time periods I shall use some shorthand, thus:

Late Bronze Age = ca. 1500-1200 B.C. Iron I = ca. 1200-1000 B.C.

Also, for the sake of convenience, I shall often refer to the former as the Canaanite era, the latter as the Israelite (or proto-Israelite) era. Throughout I capitalize Exodus and Conquest when I am referring specifically to the biblical stories and their traditions, without necessarily prejudging their historicity.

I have not encumbered the text with footnotes, although I do cite year of publication and page numbers for authors whom I quote directly. These and a few other basic works are listed by subject matter at the end of the book, so that readers who wish may delve further into the sources.

I owe a debt to nearly all of the scholars whose works I quote throughout, because I have been privileged to know nearly all of them personally, even those of the pioneer generation, and I have built on their foundations. In particular, I am grateful to my many Israeli colleagues, with whom I have worked for years viewing the land (Josh. 2:11), trying to learn the facts on the ground.

I also wish to thank my colleague Professor J. Edward Wright, who read the first draft and made many helpful suggestions on the biblical side - although of course he is not to be held accountable for any idiosyncrasies that remain.

I wrote this book in the few weeks following the death of my son Sean in the spring of 2001, since work is the only therapy I know. His memory inspired me then and now. I dedicate this work, although still in progress, to Sean, for he taught me that it is the journey, not the destination, that matters.

Tucson, Arizona May 2001

CHAPTER 1

The Current Crisis in Understanding

the Origins of Early Israel

Until modern literary-critical biblical scholarship began to emerge in the mid-to-late 19th century, the Hebrew Bible or Christian Old Testament was regarded as Scripture, as Holy Writ. Its stories were taken at face value and were read more or less literally by Jews, by Christians, and by the public at large. Indeed, in some circles this is still the case: as my favorite bumper-sticker (usually to be found on a pickup with a rifle rack) puts it: God said it; I believe it; that settles it! If only it were that simple.