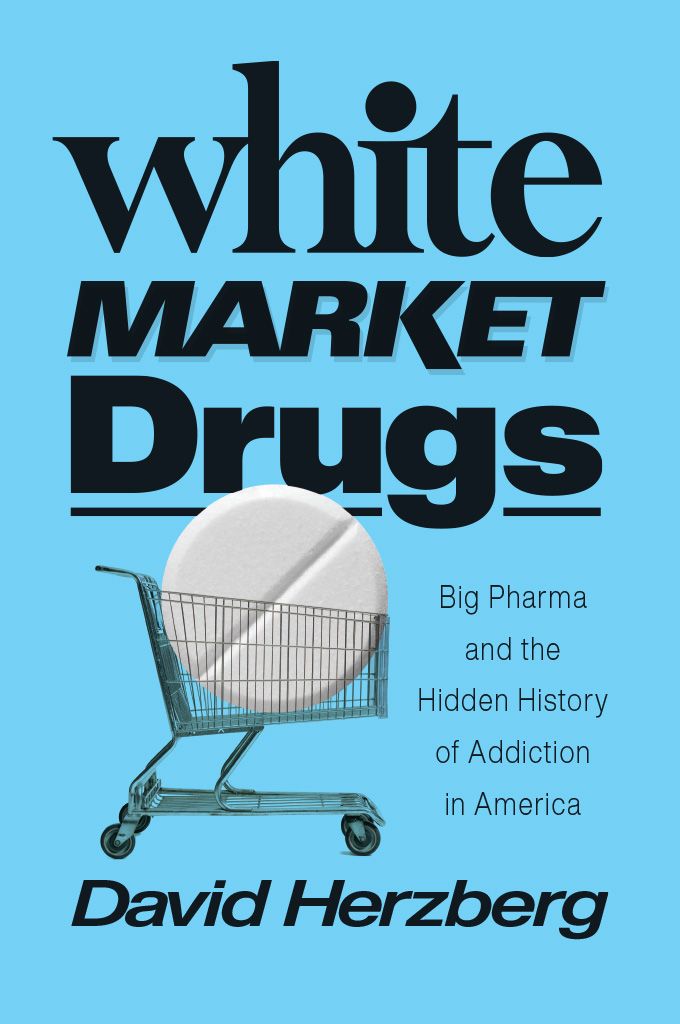

White Market Drugs

White Market Drugs

Big Pharma and the Hidden History of Addiction in America

DAVID HERZBERG

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-73188-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-73191-9 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226731919.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Herzberg, David L. (David Lowell), author.

Title: White market drugs : big pharma and the hidden history of addiction in America / David Herzberg.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020017334 | ISBN 9780226731889 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226731919 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pharmaceutical policyUnited StatesHistory. | Drug controlUnited StatesHistory. | NarcoticsUnited StatesHistory. | Drug addictionUnited StatesHistory. | Pharmaceutical industryUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC RA401.A3 H47 2020 | DDC 362.17/82dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017334

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

At the turn of the twenty-first century, America faced two seemingly contradictory drug crises. The first began with an unprecedented increase in opioid addiction, especially in rural white areas such as Maine, Appalachia, and parts of the Midwest. Most observers traced this crisis to the aggressive marketing of OxyContin, a long-acting opioid introduced by Purdue Pharma in 1996.

There was a brutal irony in this moment of twin social catastrophes: American drug control was too weak to restrain Purdue Pharma, but so strong that it sent countless people to prison. How was it possible for drug laws to have both problems at the same time?

The answer is all too obvious. In early twenty-first-century America, pharmaceuticals were not drugs. Regulating the pharmaceutical industry was seen as separate from controlling drugs, and the crisis of addiction to pharmaceutical opioids was not seen as connected in any way to the crisis of mass incarceration driven in part by drug arrests. Pharmaceuticals and drugs belonged to separate stories, involving different people and different challenges, and calling for different solutions.

This assumed difference provided cultural fuel for one of the most relentlessly sensationalized narratives about the opioid crisis: that addiction had left its traditional home among poor, urban racial minorities and was, for the first time, invading largely white suburbs and small towns, transforming wholesome children into a new breed of addict, supplied by a new breed of dealer. The crux of the typical media story on OxyContin was the defilement of white innocence: suburban cheerleader to sex worker, rural honors student to criminal.

To see the opioid crisis as new and unprecedented in this way required a radical act of forgetting. During the last 150 years, small town and suburban white communities have suffered repeated crises of addiction to pharmaceuticals. Indeed, they have been home to far more drug use and addiction than poorer communities with less access to the medical system. These previous crises were no carefully held secret; medical and popular media have been covering them breathlessly for over a century. Yet eerily, year after year, decade after decade, this coverage has recounted the same story of addiction appearing for the first time in places and people where it did not belong.

Why has addiction to pharmaceuticals been so widespread, for so long? How is it possible to continually discover it as if it were something new? What purposes are served by this bizarre, long-running national surprise?

This book answers these questions by remembering the story of what I call white markets: legal and medically approved social institutions within which the vast majority of American experiences with psychoactive drugs and addiction have taken place. White markets, I show, have been home to three major addiction crises in the modern era, far larger than any crises associated with illegal drugs. The first, at the turn of the twentieth century, began with sharp increases in medical sales of opioids and cocaine. The second, from the 1930s to the 1970s, came during a historic boom in sales of pharmaceutical sedatives and stimulants. The third, at the turn of the twenty-first century, grew from dramatic increases in medical use of all three classes of white market drugssedatives, stimulants, and opioids. These crises, I argue, all happened for the same reason: a presumption of therapeutic intent that left white markets with insufficient consumer protections. They were also all resolved through a similar set of policies, quite different from (and significantly more effective than) the punitive prohibitions of Americas drug wars. These policies involved a combination of strong regulation of large commercial suppliers and continued provision of safe, reliable drugs to people who needed them, including people who were addicted.

The story of these three crises challenges us to rethink our basic assumptions about drug use, drug addiction, and drug policy. First and foremost, it reminds us that despite its famous drug wars, America has never tried to prohibit the use of addictive drugs. Instead, vast resources have been marshaled to enable and promote use of these drugs in contexts defined as medical. For over a century, providing sedatives, stimulants, and opioids to patients has been one of the single most common therapeutic acts in American medical and pharmacy practice. This has been so consistently true, for so long, that it cannot be written off as an accident or aberration; it has been a primary function of the medical system. The driving question in American drug history has not been how to prohibit use of addictive drugs, but how to define the medicalthat is, how to determine who should have access to drugs, under what circumstances.

In theory, at least, the medical is simple to define: use that heals rather than harms. Seemingly simple terms like heal and harm are actually quite complex, however, and have been the subject of intense political conflict. Then too, since white markets have been home to the majority of addiction and drug-related harms, it would make little sense to characterize them as free of harm. Medical status did not confer special protection against addiction to the privileged type of consumer known as patients; it did not immunize pharmaceutical companies against the lure of profit; and it did not prevent physicians and pharmacists from being swept up by unwarranted enthusiasm for new drugs. For much of American history, privileged access to the medical system has meant heightened exposure to addiction and related risks.

Of course, access to white markets was not all bad. Far from it. Even during the three great crises, the majority of white market drug use did not lead to addiction or harm but was unproblematic or even beneficial. It often treated rather than caused addiction. For untold numbers of Americans, sedatives, stimulants, and opioids have been highly desirable tools for easing suffering and pursuing pleasure. In this sense, white markets have indeed been a social privilege, not a century-long conspiracy by Big Pharma or an ongoing therapeutic error by physicians and pharmacists.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).