ALSO BY LYNNE CHENEY

James Madison: A Life Reconsidered

We the People

Blue Skies, No Fences

Our 50 States

A Time for Freedom

When Washington Crossed the Delaware

A Is for Abigail

America: A Patriotic Primer

Telling the Truth

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2020 by Lynne Cheney

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2020940885

ISBN 9781101980040 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781101980064 (ebook)

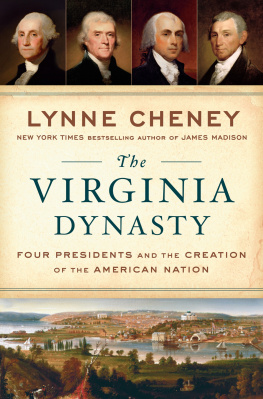

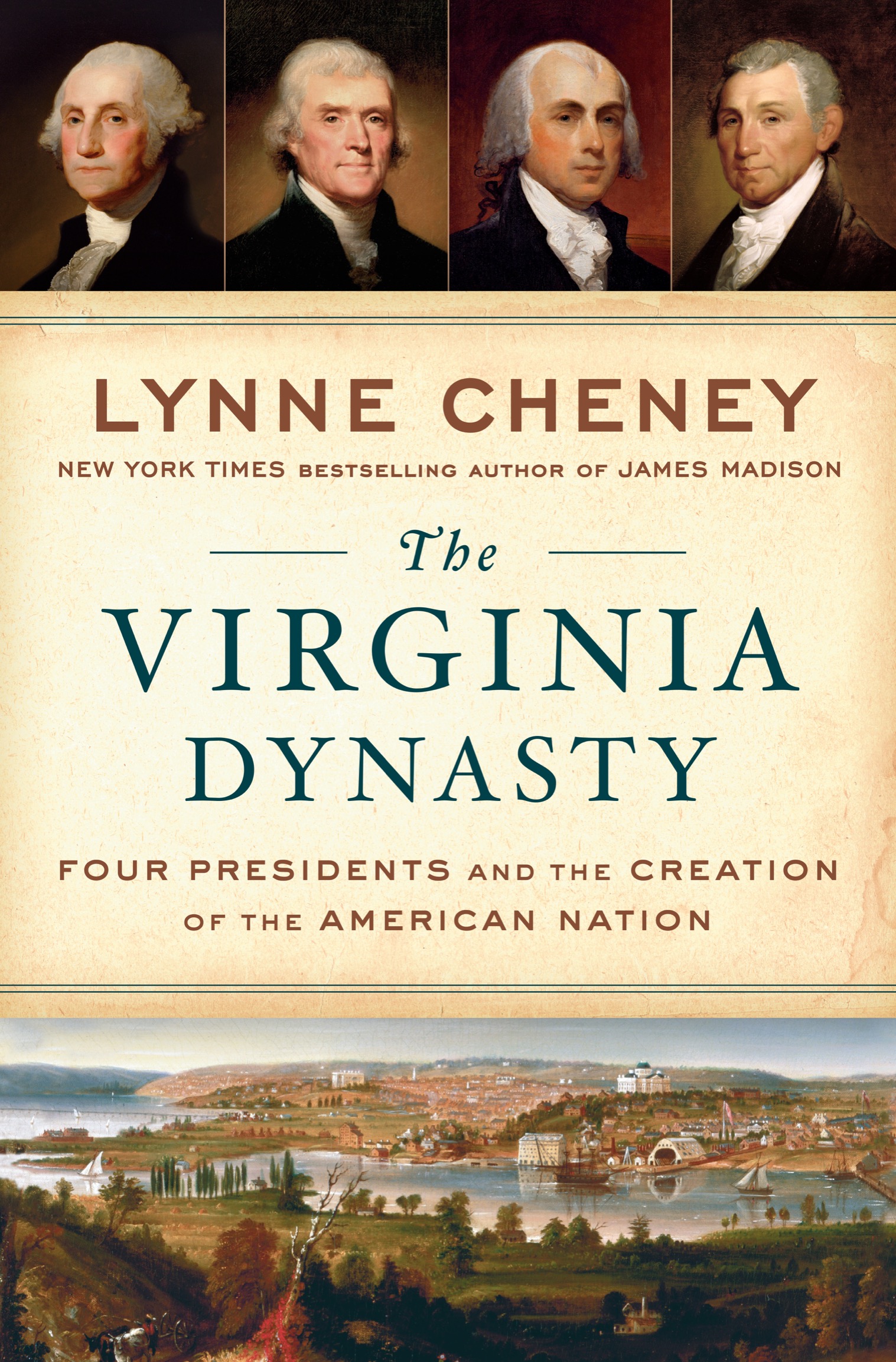

Cover design: Brianna Harden

Cover images: (top portraits, left to right) George Washington, 1796 by Gilbert Stuart, Everett - Art / Shutterstock; Thomas Jefferson, 1853 by Rembrandt Peale, GraphicaArtis / Bridgeman Images; James Madison, 19th c. by George Peter Alexander Healy, Bridgeman Images; James Monroe, 1835 by Asher Brown Durand / Bridgeman Images; (bottom image) City of Washington from Beyond the Navy Yard, 1833 by George Cooke, ART Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

pid_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

For Dick, for always

CONTENTS

Prologue

Put the spike of a drawing compass into a map of Virginia at Ferry Farm, George Washingtons boyhood home. Extend the other leg of the compass so that it reaches out sixty miles and draw a circle. Within it, not only Washington, but also Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were born, grew to manhood, and made their homes. From this small expanse of land on the North American continent came four of the nations first five presidentsa dynasty whose members led in securing independence, creating the Constitution, and building the Republic. One of them doubled the size of the United States. Another extended its border to the Pacific Ocean. Sometimes they worked as a band of brothers, but not always. They quibbled, they quarreled, and they fought. Were political parties a bane or a boon? What were the limits of dissent? How should a republic prepare for war?

George Washington, the most charismatic of the dynasty, was lionized in his lifetime and worked to become a legend in praiseworthy ways, such as embodying good character and staying above politicsor at least politics as he understood it. Tall and powerfully built, he heightened his presence with elegant dress, even wearing fashionable yellow gloves on special occasions. He was a man of few words, which enhanced his natural dignity and helped conceal his explosive temper. He had countless admirers but few friends.

Jefferson, tall, long-limbed, and with reddish hair, was known for receiving visitors in well-worn waistcoats and run-down slippers, his way of demonstrating that for all his ties to Virginias aristocracy, he was a man of the people. Gifted with a soaring imagination, he was a master of language, able to set forth ideas that would inspire generations. He delighted in everything from high art to scientific discovery to gadget building. His often-shifting views made him a hard man to know.

Madison, the most profound thinker of the group, usually dressed in black. To strangers he could seem stern, but with friends after dinner he was a charming conversationalist. A small, compact man, he could disappear in a crowd, particularly when accompanied by his glamorous wife, Dolley, but when he entered debate, as at the Constitutional Convention, his powerful mind made him impossible to ignore. A well-grounded man, he was the least likely of the dynasty to disparage others, but he was expert at digging in his heels in defense of ideas.

Monroe, the last of the Virginia dynasty, was also the last president to wear knee breeches. Old-fashioned and awkward, he let his ambition show, but kept his temper under wraps by writing blistering letters to those who offended himand not mailing them. Because he lacked the intellectual prowess of a Jefferson or Madison, he can seem a symbol of the dynastys winding down, but through a remarkable career in Congress, the diplomatic corps, and the cabinet, he learned one of the secrets to being a good president: Listen to smart people.

How to account for this gathering of talent, aspiration, and achievement? Part of the answerand all explanations of human beings are partialis the transformative time in which these men lived. As children of the Enlightenment, they imagined a society in which reason replaced dogma and individual rights were honored. Other nations had been founded in the gloomy age of ignorance and superstition, as George Washington put it, but the United States had its beginnings in an epoch when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined than at any former period. Establishing a nation built on what Washington called the researches of the human mind after social happiness was an irresistible calling, one that animated the four Virginians and drew them together.

Washington taught himself about the exceptional age into which he had been born. Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe attended schools and colleges steeped in the new learning of the Enlightenment. They studied Latin and Greek, as was expected of young gentlemen, but they also had teachers from Scotlands esteemed universities who placed great value on natural philosophy, as science was called, and moral philosophy, which concerned ethics and politics. William Small (Jeffersons beloved tutor at William and Mary), Archibald Campbell (founder of the academy where Monroe studied), and Donald Robertson (whose school Madison attended) had all breathed the air of the Scottish Enlightenment and understood well its distinctive practical side. Science and the study of man were more than ends in themselves; they could be used to better the world.

Madison attended Princeton, which was presided over by the Reverend John Witherspoon, a formidable man and the preeminent student of the Scottish Enlightenment in the colonies. In Nassau Hall, he lectured about the natural rights of life and liberty and justified the overthrow of tyrannical governments, ideas of clear application in revolutionary times. Madison was the only one of Witherspoons students to become president, but among the others were a vice president, thirty-nine members of the House of Representatives, and twenty-one senators. Witherspoon himself was a member of the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

How, one wonders, would the men of the Virginia dynasty have fared in another time? A generation earlier, revolution was not on the table, and viewed from America the Enlightenment was a mere glow on the horizon. The era in which these men lived determined their destinyas did their place on the planet.

Virginia was on the periphery of civilization, where the dictates of tradition had less force. It was easier to question assumptions about monarchy than it would have been at the imperial center. It was easier to imagine a new society in which citizens could worship as they pleased rather than bow to a long-established church.