Contents

Guide

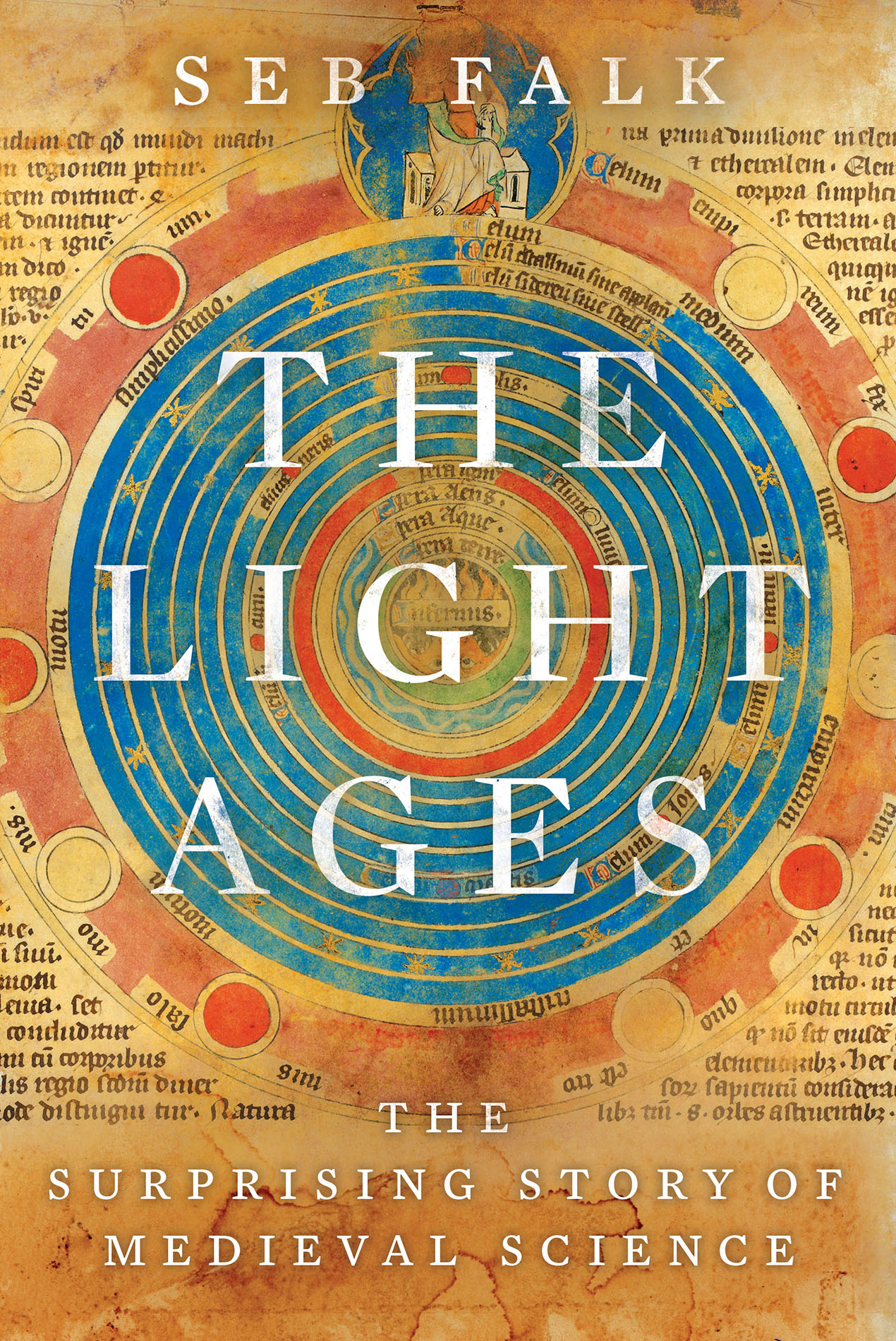

The Light Ages

The Surprising Story of Medieval Science

SEB FALK

Copyright 2020 by Seb Falk

First American Edition 2020

Originally published in the UK under the title THE LIGHT AGES:

A Medieval Journey of Discovery

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by Richard Ljoenes

Jacket art British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images

Production manager: Erin Reilly

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Falk, Seb, author.

Title: The light ages : the surprising story of medieval science / Seb Falk.

Description: First American edition. | New York, NY : W.W. Norton & Company, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020028315 | ISBN 9781324002932 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781324002949 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Science, MedievalHistory.

Classification: LCC Q124.97 .F35 2020 | DDC 509.4/0902dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028315

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To Fergus and Vivian

Bot for men sein, and soth it is,

That who that al of wisdom writ

It dulleth ofte a mannes wit

To him that schal it aldai rede,

For thilke cause, if that ye rede,

I wolde go the middel weie

And wryte a bok betwen the tweie,

Somwhat of lust, somewhat of lore,

That of the lasse or of the more

Som man mai lyke of that I wryte.

John Gower

Contents

The Light Ages

Derek Price, they said, was not socially house-trained. From the day he arrived at Christs College, whose alumni included Charles Darwin and the Queens cousin, war hero Lord Mountbatten, Price was desperate to prove himself.

One chilly morning in December 1951, he got his chance. A few months after starting his research on the history of scientific instruments, he had an appointment to visit the medieval library of Peterhouse, Cambridges oldest college. There was just one manuscript there that interested him number 75. It contained so its nineteenth-century cataloguer had hesitantly guessed directions for making an astrolabe (?). It was, as Price later recalled, a rather dull volume... and had probably hardly been opened in the last five hundred years it had been in the library.

As I opened it, the shock was considerable. The instrument pictured there was quite unlike an astrolabe or anything else immediately recognizable. The manuscript itself was beautifully clear and legible, although full of erasures and corrections exactly like an authors draft after polishing (which indeed it almost certainly is) and, above all, nearly every page was dated 1392 and written in Middle English instead of Latin...

The significance of the date was this: the most important medieval text on an instrument, Chaucers well-known Treatise on the Astrolabe , was written in 1391... The conclusion was inescapable that this text must have had something to do with Chaucer. It was an exciting chase.

The chase got hotter when Price spotted the beginning of a word: chauc. The rest was buried in the manuscripts tight nineteenth-century binding, but Price quickly persuaded the Peterhouse librarian to have the binding cut apart. On the day when the disbound leaves returned from the conservators, Price and two distinguished professors were ejected from the hushed library for whooping with raucous delight. The full word was indeed revealed to be chaucer. This dull manuscript was a draft instruction manual for a completely unknown scientific instrument. And it was seemingly written by the hand of Geoffrey Chaucer, the greatest English writer before Shakespeare.

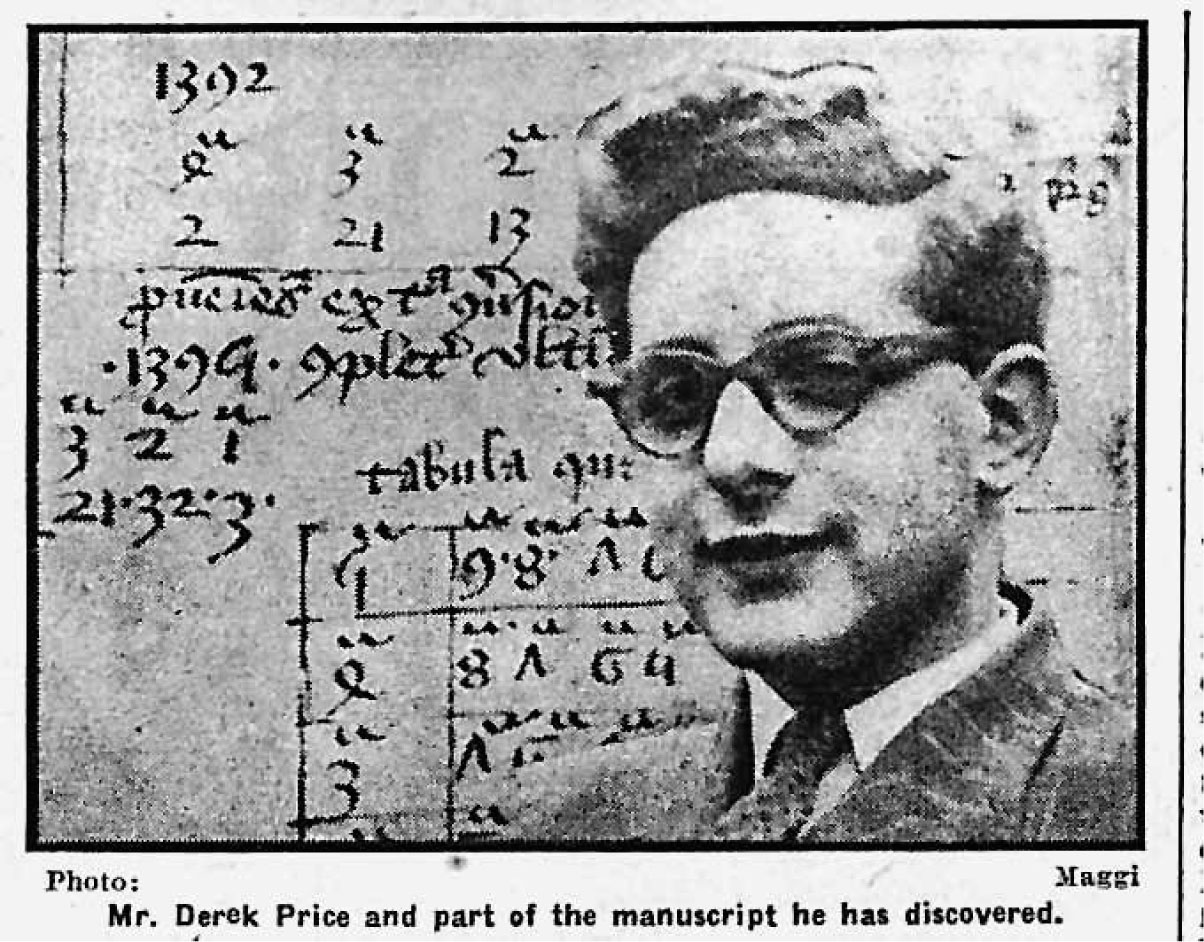

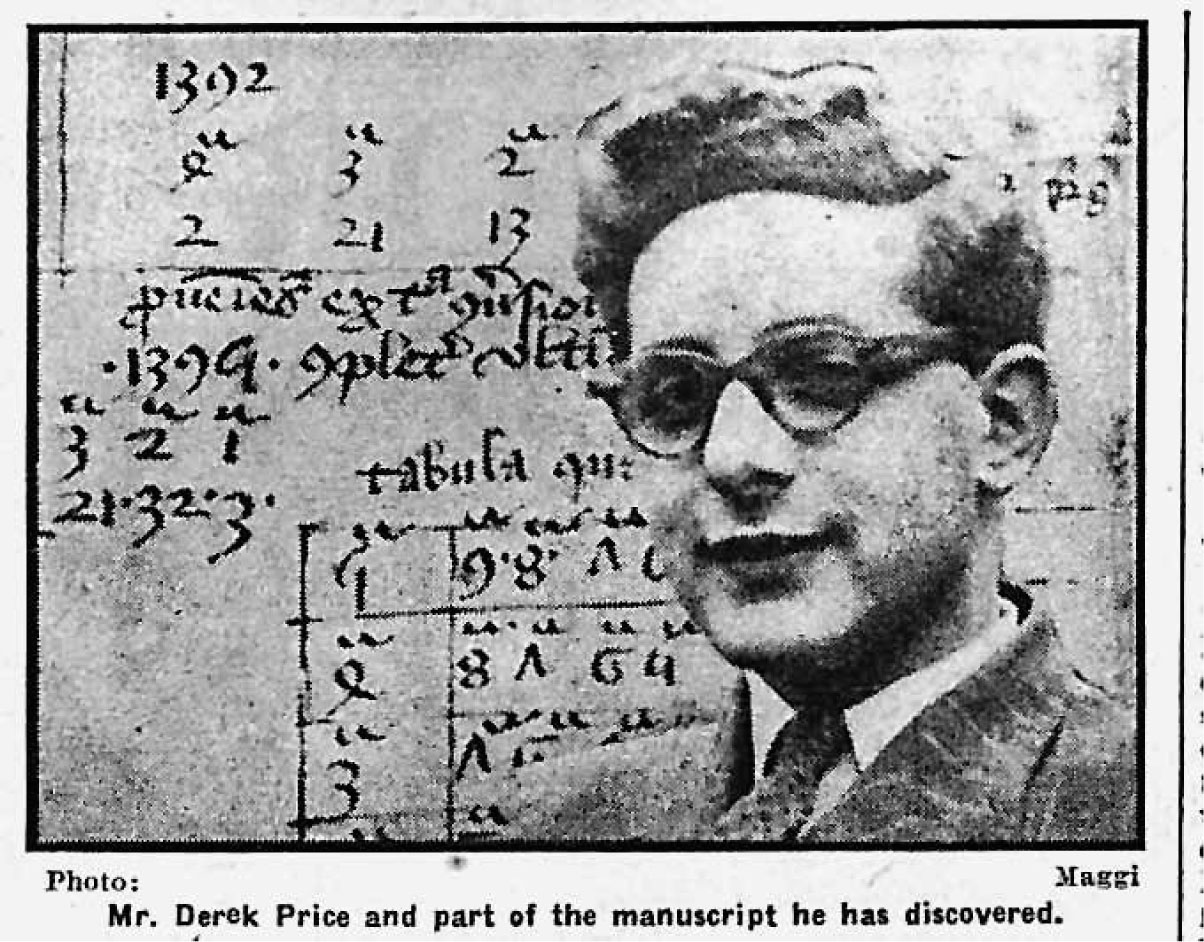

With his characteristic single-minded energy, and equally characteristic disregard for the cautious norms of Cambridge scholarship, Price rushed to publicise his discovery. Chaucer Holograph Found in Library, trumpeted the university newspaper Varsity , above a collage of the manuscript and Price, with wavy hair and thick-framed glasses, looking a little younger than his twenty-eight years ( But was Price right? Or was the Times s hesitation justified? And why did it matter?

The shock was not simply that a new work by the famous Canterbury Tales author had been discovered, but that this was a scientific treatise. Was Chaucer a Scientist Too? ran the incredulous headline in the Indian newspaper The Hindu . Never mind that historians including Price himself were already well aware that Chaucer had written another scientific-instrument manual, the Treatise on the Astrolabe . In the 1950s, just like today, the general view was that the phrase medieval science was a contradiction in terms.

It is often supposed that science began with the Renaissance. In his multimillion-selling book Cosmos (1980), the superstar of popular science, Carl Sagan, drew a timeline featuring a range of famous names and events in the history of science. After a smattering of ancient figures such as Pythagoras and Plato, around the year 400 he marked onset of Dark Ages . A wide blank space takes us almost to 1500, where we find Columbus, Leonardo. The millennium gap in the middle of the diagram, Sagan lamented, represents a poignant lost opportunity for the human species. The medieval reality, however, is a Light Age of scientific interest and inquiry.

0.1. Image of Derek Price and Peterhouse manuscript 75, published in Varsity on 23 February 1952. The collaged image placed Prices head over the crucial chaucer.

Curiously, the concept of the Dark Ages itself comes from the medieval world. Early Christians had written of the pagan darkness before the birth of Jesus. Humanist scholars in fourteenth-century Italy took that old Christian metaphor and turned it on its head. They described the darkness of a supposed cultural decline, between the fall of the Roman empire around 400 and their own Renaissance revival of classical learning. For scholars keen to divide human history into easy chunks, it was both convenient and evocative. It gave them an enemy to define themselves against. That became particularly appealing where the Protestant Reformation took hold, and earlier centuries could be mocked as enslaved to Roman Catholic superstition. Introducing a selection of English literature in 1605, the Anglican antiquarian William Camden dismissed the Middle Ages as overcast with darke clouds, or rather thicke fogges of ignorance. But as historians developed a new appreciation for the brilliance of medieval culture and learning, the term Dark Ages began a steady decline. It lingered longer in the English-speaking world, where it served as a shorthand for Britain before the 1066 watershed of the Norman Conquest. Even there, though, it could not last, and historians now prefer the less pejorative term Early Middle Ages.