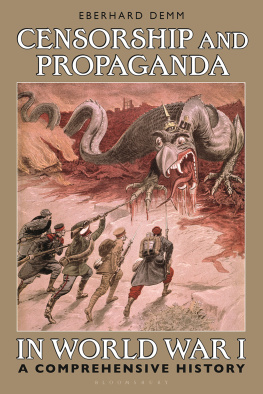

CENSORSHIP AND PROPAGANDA IN WORLD WAR I CENSORSHIP AND PROPAGANDA IN WORLD WAR I A Comprehensive History Eberhard Demm  BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, I.B. TAURIS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2019 Copyright Eberhard Demm 2019 Eberhard Demm has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Terry Woodley Cover image Sus au Monstre, Le Petit Journal , 30 September 1914. Five Allied soldiers are courageously attacking a frightful dragon recognizable as German and Austrian by the spiked helmet and the Austrian equivalent. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France.

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, I.B. TAURIS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2019 Copyright Eberhard Demm 2019 Eberhard Demm has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Terry Woodley Cover image Sus au Monstre, Le Petit Journal , 30 September 1914. Five Allied soldiers are courageously attacking a frightful dragon recognizable as German and Austrian by the spiked helmet and the Austrian equivalent. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: HB: 978-1-7845-3851-4 ePDF: 978-1-3501-1861-4 eBook: 978-1-3501-1859-1 Series: International Library of Twentieth Century History To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters. Contents Chapter 1

Censorship Chapter 2

Propaganda Aims and Organization Chapter 3

What Were the Principal Arguments of Propaganda Chapter 4

How did the Techniques and the Distribution of Propaganda Function? Chapter 5

How were Entertainment and the Visual arts Transformed by Propaganda? Chapter 6

Which Groups Were Especially Targeted and How Did They React? Chapter 7

Selected Propagandists Eight Profiles Chapter 8

Anti-War Propaganda Chapter 9

How Successful Were Censorship and Propaganda? Chapter 10

Still Going On: The Legacy of War Censorship and Propaganda Chapter 11

Organograms of Censorship and Propaganda Chapter 12

Iconography: Figures 1 to 38 The first comprehensive book on World War I Propaganda was published in 1927 by the American political scientist Harold D. Lasswell and re-edited in 1938 and 1971. Since this pioneering work, numerous studies on the propaganda of single countries or on special aspects of this propaganda have appeared, but so far no complete monograph. A book by the German journalist Klaus Jrgen Bremm entitled Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg (2013) does not present the whole story either, but compares only German propaganda methods with those of Britain, France and the United States.

What are the reasons for this shortcoming? The importance of hate has also been largely discarded, especially as far as the soldiers are concerned. Several scholars concur that neither the correspondence of the soldiers nor their trench journals contain hateful invectives or the demonizing of the enemy in the style of atrocity propaganda.were so patriotic and consented to the war. The leading elites knew very well that only permanent brainwashing, rigorous censorship and unrelenting persecution of pacifist initiatives enabled them to continue the war (see motto to ). Opposed to the conception of the pronnist consent school is another group of historians around the Collectif de Recherche International et de Dbat sur la Guerre de 19141918 (CRID). Known as coercion school, they argue that the population refused the war and had to be coerced by censorship, state-directed propaganda and brutal discipline at the front. Although I feel closer to the ideas of the CRID, I cannot entirely accept their conception either.

The social responses to the war and to war propaganda were dominated neither by patriotic acceptance nor by violent refusal and dissent. As Purseigle puts it, such a dichotomy belies the critical importance of the moral, cultural and political ambivalences that underlie and determine social responses to the First World War. They depended on several variables: class, gender, religion, social and professional milieu, the political convictions, the military situation and the degree of personal frustration. Last but not least, they varied over time (see pp. 1835). In 2014, a group of historians around Oliver Janz launched the www.encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net, the largest network of World War I researchers.

It attributes an appropriate place to propaganda at home and abroad with numerous contributions on the individual states as well as comparative surveys. I had been invited to write survey articles on Censorship, Propaganda at home and abroad and Caricatures, and it was the very flattering expertises by the section editors David Welch, University of Kent, and Dominik Geppert, University of Bonn, which have encouraged me to expand my work into this book. It will thus present a comprehensive history of censorship and propaganda in World War I. It is based on sources and secondary literature from Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Belgium, the United States, Germany, Austria and Turkey. I have also benefited from my own pertinent publications on this subject published over the last 35 years. Earlier versions of several chapters of this book originally appeared in abridged form in 201617 in the above-mentioned encyclopaedia.

The section about children ( ) is a modified and extended version of an earlier draft of mine, the latter having been translated by Stefan Grner and Markus Raasch into German and published in 2016 under the title Kinder und Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg. Eine transnationale Perspektive in: Kinder und Krieg, edited by them and Alexander Denzler as supplement no. 68 of the Historische Zeitschrift . Kim Oosterlink and Vronique Pouillard for having authorized me to use their unpublished internet article and Martin Schramm for allowing me to copy two organograms from his book. I was overwhelmed by the wealth of information, a fact which, however, tended to inflate the references necessary for seven countries at the expense of the text. On the other hand, several aspects of this book are underexposed in research, and the consultation of archival sources would have been desirable.

Unfortunately two applications for financial support to the historically oriented Foundation Gerda Henkel were turned down. In case supplementary information seemed necessary, I was therefore limited to the archives of Paris and Berlin, easily within my reach. All foreign language quotes have been translated into English. In the instances that I could not get hold of the English translations of foreign monographs, the original editions had to be quoted. According to the iconic turn, I have used many cartoons as sources, an approach I had already applied in 1988 and 1993. However, I could not reproduce all of them here because the number of illustrations was limited.

I have therefore applied a reverse iconic turn interpreting certain cartoons without giving the images. Some critics might object to this exuberance of cartoons discussed in the text, but people who enjoy laughing in Britain certainly a majority will forgive me. I do consider cartoons as one of the most influential propaganda vehicles, a view I share with the German publicist Maximilian Harden who already before the war wrote that no other sort of publication can have such an effect on public opinion as the illustrated satirical magazine. I would like to thank Hew Strachan (University of Oxford), Arnd Bauerkmper (Free University of Berlin/London School of Economics), Elise Julien (Universit de Lille), Mark Cornwall (University of Southampton), Jrgen von Ungern-Sternberg (University of Basel) and Charles Sorrie (University of Trent/Carnegie Council New York) for having reviewed particular chapters of the book. I am especially grateful to Stefan Goebel (University of Kent) and Adrian Gregory (University of Oxford) who took the great trouble of reading the whole draft and whose valuable commentaries greatly helped me to improve the book. I would also like to thank Lester Crook of the editing house of I.B.Tauris for his helpful counsel and kind support.

Next page

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, I.B. TAURIS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2019 Copyright Eberhard Demm 2019 Eberhard Demm has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Terry Woodley Cover image Sus au Monstre, Le Petit Journal , 30 September 1914. Five Allied soldiers are courageously attacking a frightful dragon recognizable as German and Austrian by the spiked helmet and the Austrian equivalent. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France.

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, I.B. TAURIS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2019 Copyright Eberhard Demm 2019 Eberhard Demm has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Terry Woodley Cover image Sus au Monstre, Le Petit Journal , 30 September 1914. Five Allied soldiers are courageously attacking a frightful dragon recognizable as German and Austrian by the spiked helmet and the Austrian equivalent. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France. 326 Courtesy of the Bibliothque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine (BDIC) Nanterre, France.