1. An Introduction

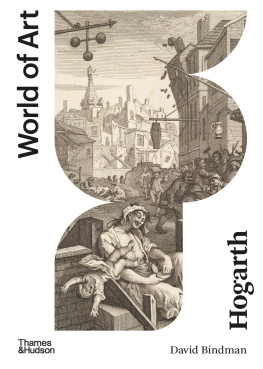

Within the wider fields of art history and visual culture, the focus of this book is early twentieth century pictorial conflict propaganda related to the First World War. This investigation sets out to isolate a specific visual construct not usually associated with artwork of this genus, and thereby explore what its presence within the works we study represents. The construct utilised as a tool for the unpacking of the imagery is not one that has been chosen at random, but, rather, selected for its genealogical legacy. Of equal importance is the constructs connotation as both a literal and metaphorical representation of movement. The pertinence of this latter consideration lies in the concept of a propagandist promotion of an alternate reality as a challenge to a current real. Consequently, the potential for circular cause and consequence relating to competing constructions of the real suggests conditions of possibility whereby the metaphorical movement between them can be aesthetically represented by a literal, visual construct. The construct serving as a pictorial trope deemed to represent not only movement but movement at its most beautiful, thereby forming a focus to attract the viewer, is the serpentine line that in 1745 artist and theorist William Hogarth scribed on a paint palette and titled THE LINE OF BEAUTY [capitals in the original], as exemplified in Fig.

Fig. 1.1

The Painter and his Pug 1745 (William Hogarth) (Tate, London 2015)

In trying to ascertain a grammar within the artworks he was being forced by convention to copy, Hogarth sought a language he could interpret, of which the serpentine curvethe line of beauty became the catalyst, as he was later to record in his 1753 book The Analysis of Beauty. Joseph Burke comments that for Hogarth Memorizing was helped by a natural impulse to abstract the salient and speaks of the artist whose predilection is for seizing the essential in the abbreviated form. and the importance of the line of beauty as a visible continuum will be demonstrated as this book progresses. There is a correlation between these observations and the reasoning that lies behind the construction of concise propagandist messaging conceived for the specific purpose of distribution via, for example, the pictorial poster. For this medium to be effective the propagandist needs to create imagery comprising visual constructs capable of striking the viewer, in order for each individual to perceive and subsequently extract that which the propagandist considers to be crucial.

The propaganda artwork under examination here is primarily restricted to that associated with the First World War, although the premise of this investigation suggests a genealogy which threads into other eras and these are therefore acknowledged throughout. However, the importance of this era is that it is in these early years of the twentieth century that the pictorial poster was first exploited by the state and subsequently used as a tool for the distribution of propagandist messaging. In addition, propaganda as a concept was beginning to be considered in the context we now understand, a point examined later in this chapter. Of prime import is the recognition that

As the wars meaning began to be enveloped in a fog of existential questioning, the integrity of the real world, the visible and ordered world, was undermined. As the war called into question the rational connections of the prewar worldthe nexus, that is, or cause and effectthe meaning of civilization as tangible achievement was assaulted, as was the nineteenth-century view that all history represented progress.

Certainly in Britain at least a tiny social elite held the threads of social, economic and political power firmly in their grasp,, inevitably instigated a counter-propagandist aesthetic response, regardless of whether or not the artists intention was consciously reactive.

Fig. 1.2

2nd City of London Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (Recruits Required at Once to Complete this Fine Battalion) 1915 (Savile Lumley)

The direct association of the Savile Lumley poster (Fig. Important to assert at this point, however, is that the isolating of this visual trope, whether a complete or incomplete construction, is not about testing the attraction of the line deemed to be a line of beauty for the specific purpose of proving its effect. This study concentrates instead on recognising the presence of the line within artworksas Hogarth practisedyet with the focus upon artworks utilised for the distribution of conflict propaganda, and what the existence of the line of beauty as a contributory compositional element within them potentially signifies from both a literal and metaphorical point of view. The focus upon early twentieth-century pictorial conflict propaganda examined through the employment of an eighteenth-century aesthetic theory produces a unique combination of elements that not only affect each other and therefore the whole, but also illustrate a genealogical thread with the potential to permeate into the twenty-first century.

Propaganda is a complex subject, and differences undoubtedly exist between what is considered to be propaganda and what is meant by the more general term of information. Despite their close association, any discrepancy may feasibly lie in the propagandists aim of leaving the propagandised individual with an impression rather than merely facts or figures. is noteworthy, because dissemination of information is a pertinent expression when considered not only in the context of the distribution of propaganda in general, but in relation to a more focussed distribution in particular, as is the case during times of conflict. Moreover,

The public accelerates the transformation of information into propaganda because public opinion generally prefers the clarity of myth (propagandas specialty) to a chaotic profusion of facts, and there is simply too much information in circulation for most people to process.

This highlights the relevance of a concise propagandist message in focussing the attention of the propagandee, and the medium of, for example, the poster as a method for distribution which includes within its composition a construct with the ability to attractsuch as the line of beauty is productive for the purpose. During the twentieth century the dictionary definition of the word propaganda changed, from a 1913 designation of any organization or plan for spreading a particular doctrine or a system of principles and the ability to effectively communicate visually to the masses requires design that instigates instantaneous and efficient attraction. It is therefore productive for conflict propaganda poster art, and the inevitable artistic counter-response, to be not only examined from an aesthetic as well as political point of view, but, in employing a particular visual construct to assist in effecting this objective, it becomes an innovative means by which propaganda in general and in relation to the First World War in particular can be re-evaluated and the historical contexts assessed. Hogarths concept of a line of beauty therefore serves as an apposite focus in this regard.

In addition to the line of beauty there is further historical association linking Hogarth, his ideas and subsequent interpretations, to early twentieth-century pictorial propaganda that lies in the engraved print of the eighteenth century and its parallels with the poster. Marshall McLuhan declares that With print the discovery of the vernacular as a PA system was immediate, and these observations are reflected in Tom Bryders more contemporary assertion that