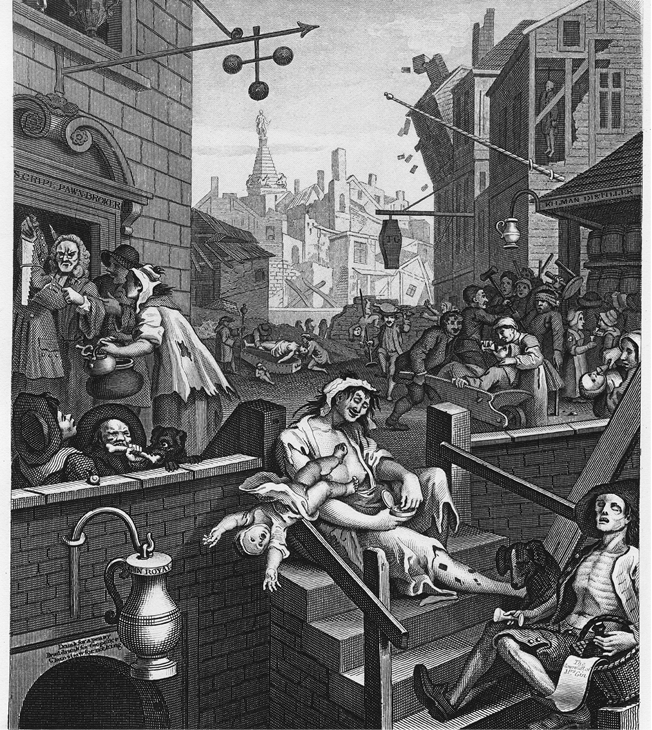

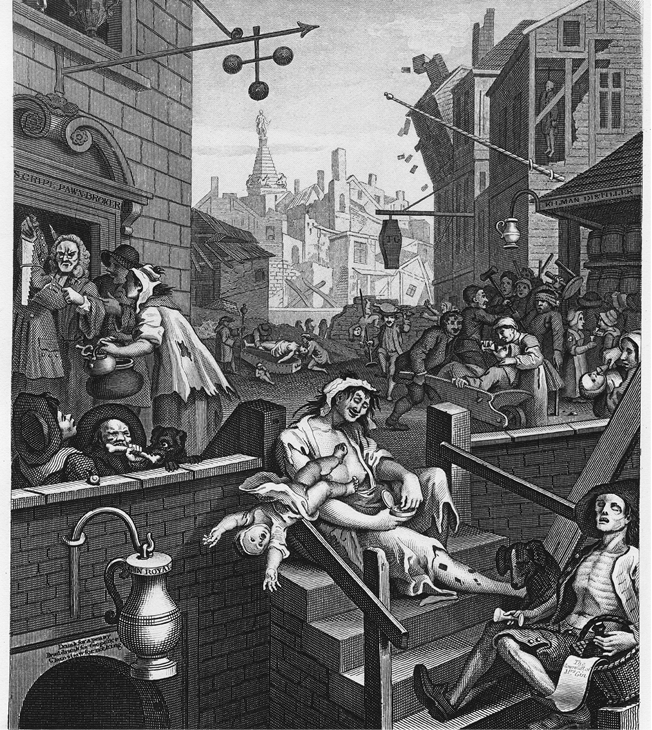

The defining image of the gin craze:

William Hogarths Gin Lane, 1751.

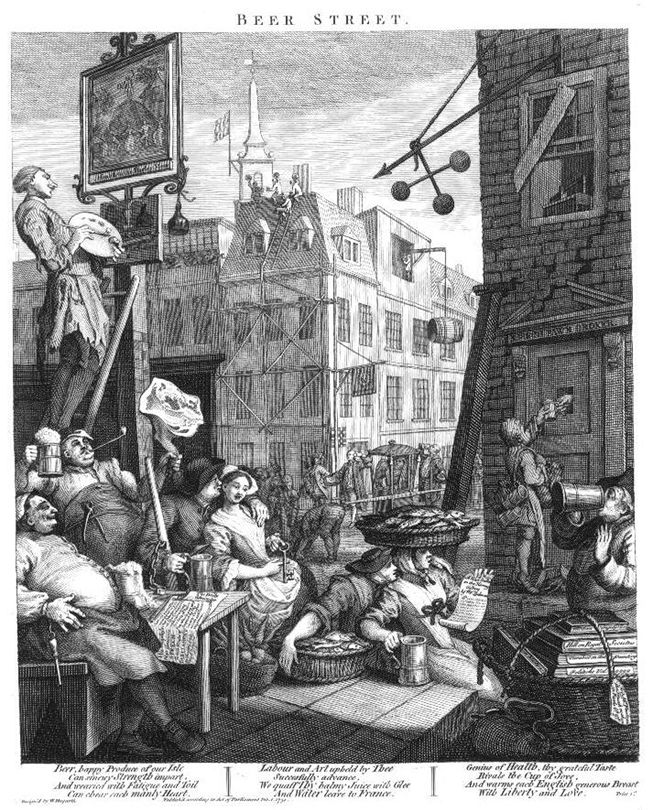

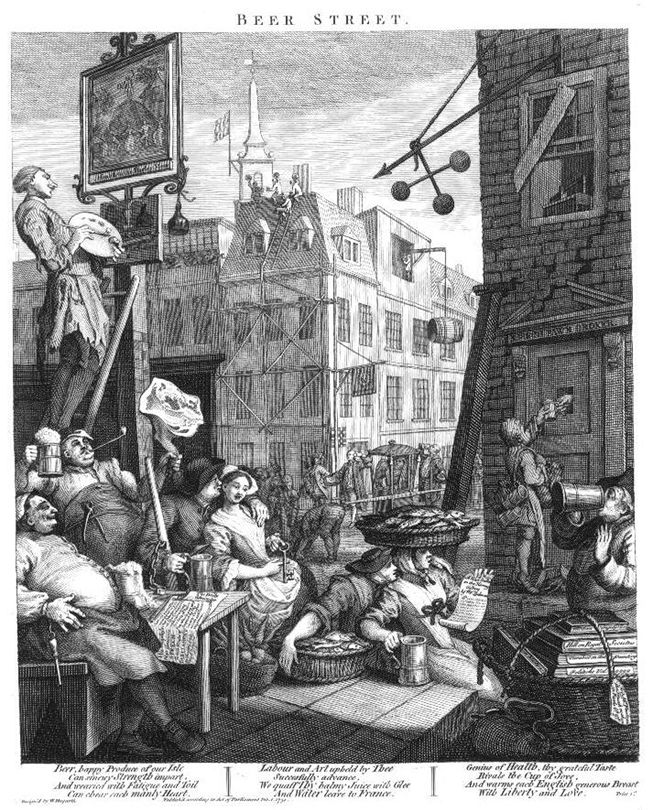

William Hogarths Beer Street, 1751.

The companion piece to Gin Lane, less well-known

but just as loaded with moral meaning.

THE

BOOK OF GIN

Richard Barnett

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2011 by Richard Barnett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or .

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Dedalus Books

as The Dedalus Book of Gin

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9409-1

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

To Matthew Barnett

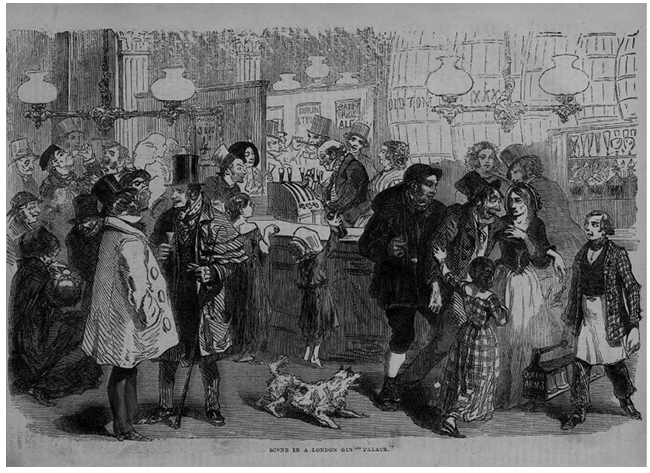

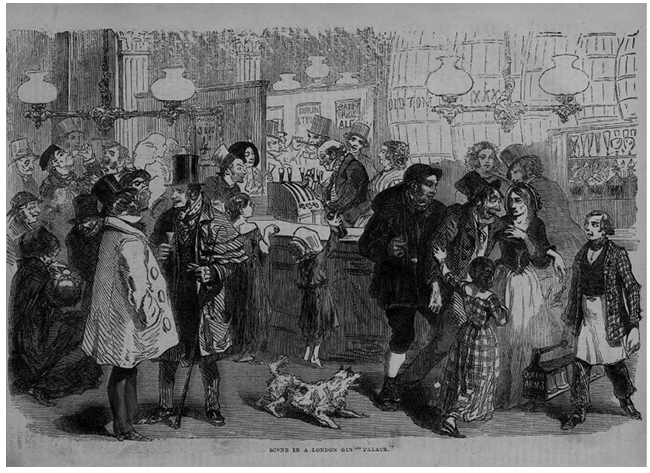

Londons Victorian gin palaces: gaily lit and full of bustling

conviviality, but also the setting for violence, obscenity

and despair. Scene in a London Gin Palace, The Working Mans

Friend, and Family Instructor, vol. 1 no 4, 25 Oct 1851, p 56.

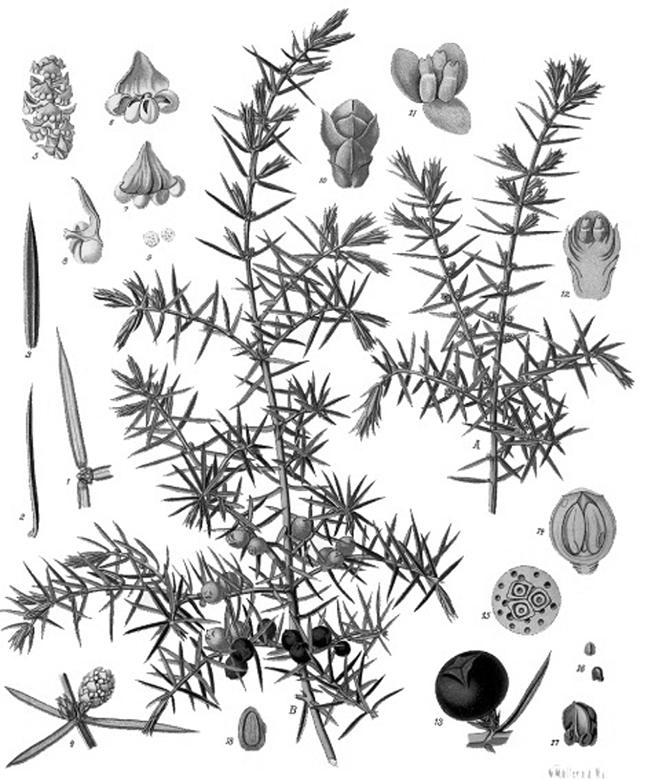

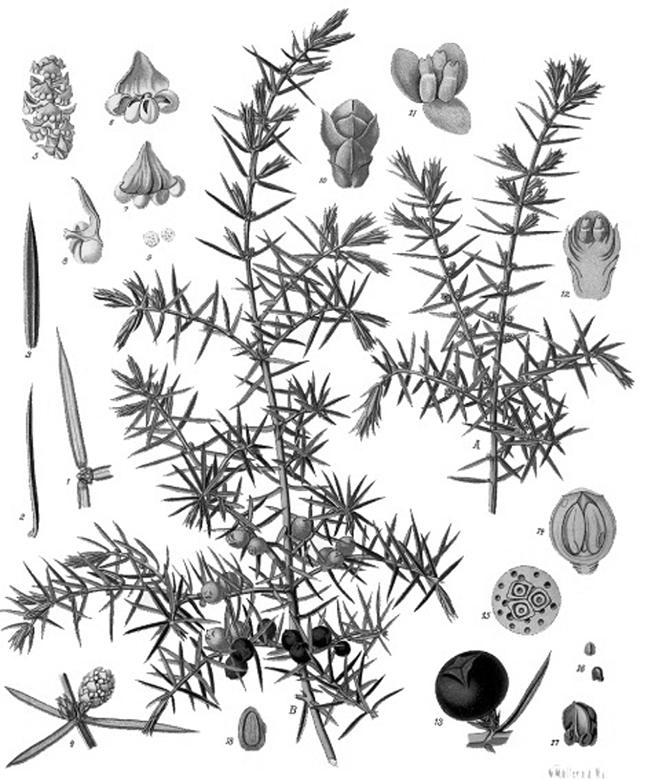

Junipersacred herb, medicine, and one of the two crucial

ingredients in gin. Juniperus communis, from Franz Eugen

Khler, Khlers Medizinal-Pflanzen, 3 vols, Berlin, 1897.

Contents

Prologue

The Murder of Mrs. Atkinson

Epilogue

Gin Renaissance

Appendix One

Selected Texts

Appendix Two

The Hogarth Sampler

Prologue

The Murder of Mrs. Atkinson

O n the morning of Wednesday 23rd February 1732 a prisoner was brought up from the dank, cramped cells of Newgate Prison into the open-fronted courthouse of Londons Old Bailey. Robert Atkinsona leather-worker from the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fieldswas on trial for his life, and he knew that, if found guilty, he would be hanged before the crowd at Tyburn. Atkinson stood accused, in the eighteenth centurys vivid, precise legal language, of murdering his mother:

, upon a Pavement of Tiles below, and by which fall her Skull was broke, and she receivd one mortal Bruise, of which she instantly dyd, the 15th of this Instant February.

The case against Atkinson seems, at first glance, to have been unanswerable. He lived with his mother, Ann, and her maidservant, Mary, in rooms above his shop. Mary testified that on the night of the crime, she had gone to bed just after midnight, but her mistress had stayed up to let her son in when he returned. Woken in the small hours by Atkinson battering on the front door, she heard him bellow Damn ye, ye old bitch, do ye think Ill be lockd up in my own House? Ann let him in, entreating him to go quietly to bed, but he had other things on his mind. He burst into Marys room:

I was very much frighted, for he was stark naked without his Shirt. Sir, says I, you had much better go to Bed: No, says he, I will have a Buss first. He came to my Bed-side, and as he did not offer any Rudeness, I sufferd him to kiss me once or twice, in hopes that he would then go away. But instead of that, he got upon the Bed (outside the Bed-Clothes) and lay upon me very hard, and endeavourd to put his Hands into the Bed, but with much difficulty I kept them out.

At this moment his mother entered the room, catching her son on the cusp of a bodice-ripping violation: You Dog, said she, what business have you upon the Maids Bed? Atkinson turned on her, and she tried to slip past him into a cupboard, but he seized her and threw her out of the room. Mary did not see the rest of the incident: she heard a great Scuffle, and a Struggling in the Passage at the Stairs Head as if he was running after her, and she was endeavouring to get away from him. In the next moment Ann tumbled down the stairs with such violence as if Part of the House had falln with her. After this she made no sound, not even a groan.

How could Atkinson possibly justify his actions? A coroners inquest had indicted him for murder, and he did not dispute that his mother had died after a brutal quarrel. Indeed, in the heat of the moment he appeared to have admitted his guilt. Seeing his mother lying at the foot of the stairs, he cried out Damn the old Bitch, I have murderd her, and I shall hang for it. Atkinsons defence hinged upon intoxication, and no ordinary intoxicationthe vicious, malevolent haze induced by gin. Cross-examining Mary, he forced her to admit that her mistress was a regular and heavy drinker, who had rounded off her last evening on earth with half a Pint of Gin and Bitter (I think they call it). Mary fought backI know she would drink a great deal; but she was so much used to it, that it would hardly disorder herbut she acknowledged that Ann was almost dead drunk by the time he had returned. And Atkinson himself had spent the night in a circuit of local taverns and gin-shops, enjoying a binge which had, he admitted, inflamed his great Passion.

Gin, it seems, enabled Atkinson to get away with murder. The jury found him not guilty, concluding that his mothers death was not even manslaughter but a mere accident, and he left the dock a free man. And this episode of gin-fuelled violence was far from unique. Leaf through the Newgate Calendar, the Ordinary of Newgates Accounts or the Proceedings of the Old Bailey for any year in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, and you will find dozens of similar examples. To many of Atkinsons contemporaries, these cases proved that English law and society were dissolving in a flood of cheap gin. This episodethe gin crazehas had a profound effect on our historical perceptions of gin, but it also captures a truth central to the story of this book. Gin is not (like absinthe) the drink of velvet-trousered aesthetes, nor is it (like port) the toast of respectable merchants and scholars, nor (like ale) the refreshment of peasants in the meadows of Merry England. It is urban, and it possessesor has been said to possessall the vices and virtues of urban life.

What is gin, this liquid fire both pleasurable and deadly? One place to start is with Atkinsons and Hogarths contemporary, Samuel Johnson. In his mighty Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755, Johnson defined gin (contracted from GENEVA) as from juniper berries. As any modern master distiller will tell you, Johnson slightly missed his mark here: gin is not distilled from juniper berries, but is rather a neutral spirit flavored principally (though not exclusively) with juniper. The best base spirit is produced from grain or maize, though it can be (and has been) made from almost anything that contains enough carbohydrate to produce alcohol when it ferments. It is rectified, or, in other words, distilled at least twiceonce or more to produce the base spirit, and once or more with juniper berries and other botanicals to develop the flavor. And it is un-agedno years or decades in sherry casks, but as near as possible straight from the still into the bottle.

Next page