Introduction

The first use of the word gin in printed English can be found in Bernard Mandevilles The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices, Publick Benefits (1714):

Nothing is more destructive, either in regard to the Health or the Vigilance and Industry of the Poor than the infamous Liquor, the name of which derived from juniper-berries in Dutch, is now, by frequent use and the Laconick spirit of the nation, from a word of middling length shrunk into a Monosyllable, Intoxicating Gin, that charms the unactive, the desperate, and crazy of either Sex It is a fiery Lake that sets the Brain in Flame, burns up the Entrails, and scorches every Part within; and at the same time a Lethe of Oblivion, in which the Wretch immersd drowns his most pinching Cares.

What Mandeville describes here so passionately is the toxic alcohol that almost crippled London during the Gin Craze of the 1700s. Surprisingly, it is this same killer gin that evolved into the classic drink of modern times.

Every spirit be it gin, whisky, rum or brandy has a tale to tell. Gins story is rife with contradiction. It has been the drink of both kings and commoners. It inspired the first modern drug craze in eighteenth-century London, yet London Dry gin went on to become the embodiment of sophistication in the dry Martini. In America, it was both saviour and demon a medicinal aide in the original Cocktail and a pariah during Prohibition. And, while gin is enshrined in modern bar culture, it still battles the remnants of a negative reputation, as seen in expressions like gin-mills, gin-soaked and gin-joints.

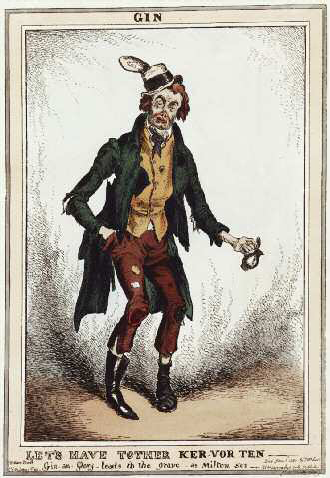

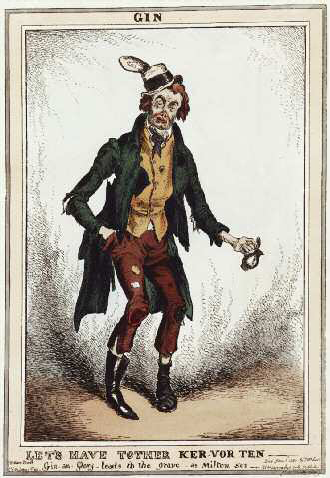

William Heath, Gin: Lets Have Tother, c. 1880s, hand-coloured etching. Decrying the effects of gin drinking, the caption at the bottom reads Gin an Glory leads to the grave as Milton ses.

Of all the spirits, gin is quite possibly the most beloved and the most berated. Those who enjoy the juniper-based liquor often drink it to the exclusion of all others. Those who favour a different poison loudly decry gins charms, claiming that, as one poetic barfly pronounced, gin tastes like Christmas trees smell. To some extent, that piney character is gins defining glory and its inevitable curse.

John Collier, Be Here, Old and Merry Kate, and Nan, and Bess, c. 1773, engraving. This post-Gin Craze caricature criticizes both gin-drinking and women imbibing. The woman on the left downs a goblet of gin; the woman on the right holds a punch bowl full of popular gin punch.

Juniper, gins key flavouring ingredient, has been used since ancient times for its medicinal benefits. Indeed, juniperscurative properties were so well-accepted that it was a natural, if somewhat erroneous, transition from healthful tonic to therapeutic spirit. Whether used medically or recreationally, gins singular character is determined by the juniper plants aromatic berries, properly referred to as cones. Simply defined, then, gin is primarily a grain-based spirit, distilled with a variety of botanicals, most frequently and prominently juniper.

Yet this description is somewhat facile; gin is far more than a fragrant alcoholic beverage. Rather, it is a spyglass through which one can trace social, political and even agricultural developments. As the Mandeville passage so clearly illustrates, the story of gin is a story of discoveries. For example, while most people immediately think of Great Britain when they think of gin, its official birthplace is thirteenth-century Flanders. There, gin began life as jenever, the Dutch word for juniper.

Juniper berries, the classic botanical for flavouring gin.

Genever, the English spelling of jenever, is a vastly different animal from the clear, crisp liquid that most people sip intheir gin and tonic. Being primarily flavoured with juniper, it is still considered gin by definition, but it has more in common with the malt-like sweetness of whisky.

Publicity card depicting the the Louis Mees distillery in Antwerp, c. 1900.

In the 1700s, the English acquired a taste for genever, but their distillers were unable to replicate it. Consequently, during the Gin Craze which blossomed a few years after Mandevilles observations, English gin had more in common with moonshine. In the 1800s, this rough product evolved into a style known as Old Tom, which favoured botanicals a combination of herbs, spices and other ingredients that give each gin its unique flavour profile as well as sweetening to cater to the taste of the times.