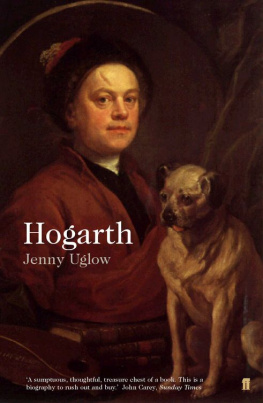

The Painter and his Pug, 1745

About the Author

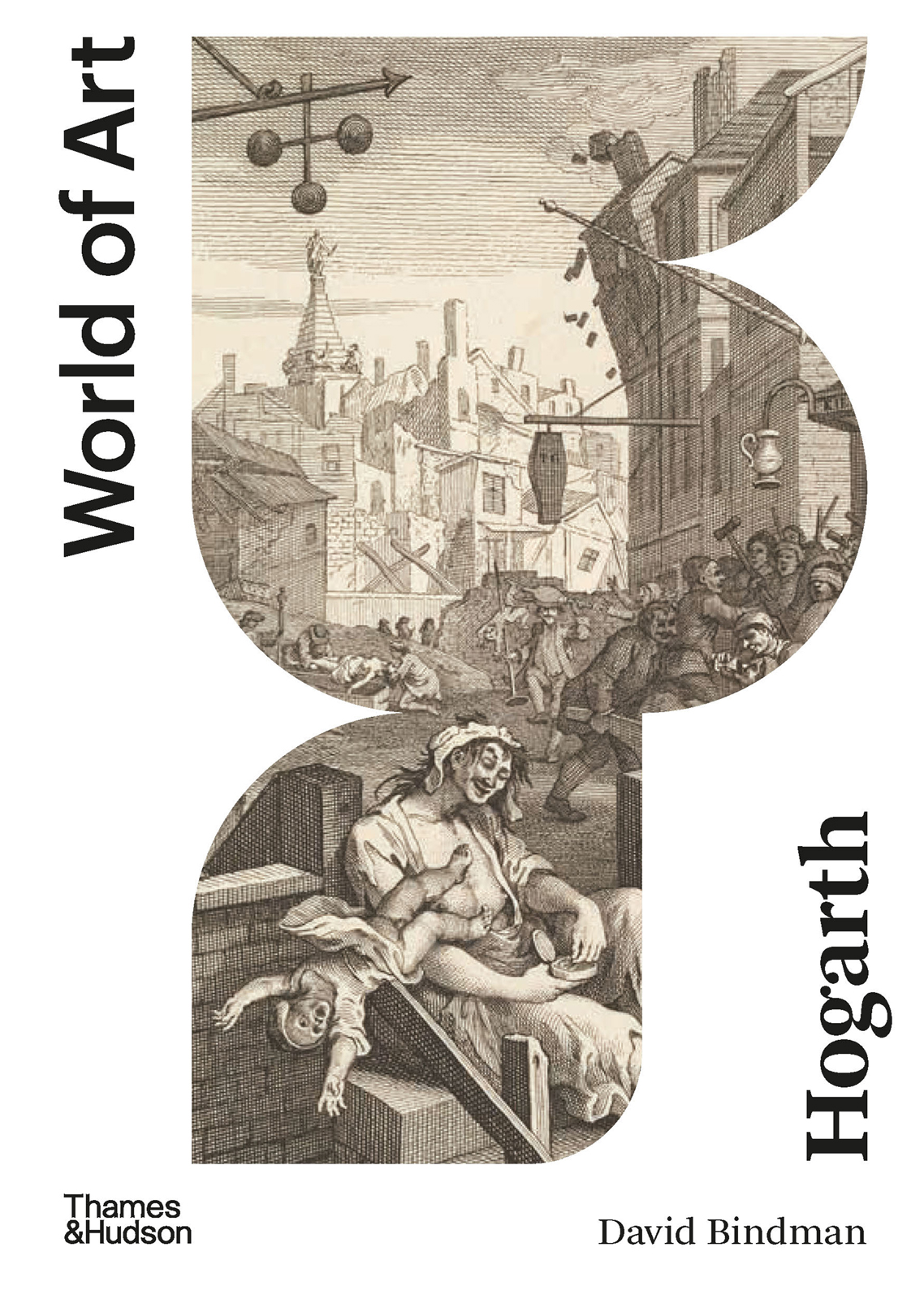

David Bindman is Emeritus Professor of the History of Art at University College London. He is currently a Fellow of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University, and he was Visiting Professor of History of Art at Harvard from 2011 to 2017. His publications include Blake as an Artist (1977), Hogarth and his Times: Serious Comedy (1997) and Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the Eighteenth Century (2002). Since 2006 he has been the editor with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. of the series The Image of the Black in Western Art, in twelve volumes so far.

Contents

It is now forty years since I wrote the text of the first edition of this work, which raises the questions: what has been learned about Hogarth since then? What has been added to the stock of information about Hogarth over the last forty years, and what have I learned over that period? A number of previously unknown Hogarth paintings have surfaced, including some notable portraits, especially two painted for the 2nd Earl of Macclesfield one of the Earl himself (private collection) and the other of his close friend the mathematician William Jones, FRS (National Portrait Gallery).[]

Among the many learned publications and exhibitions devoted to Hogarth over the period, perhaps the single most significant has been the long-awaited and much needed complete catalogue of Hogarths paintings by Elizabeth Einberg, published by Yale University Press in 2016, replacing the previous and now seriously outdated attempt at a catalogue raisonn by R. B. Beckett, published in 1949. Apart from adding numerous portraits in private collections to Hogarths oeuvre, Einberg also rejected by omission a number of early paintings that, for reasons I will discuss in , had distorted the true picture of Hogarths origins as a painter.

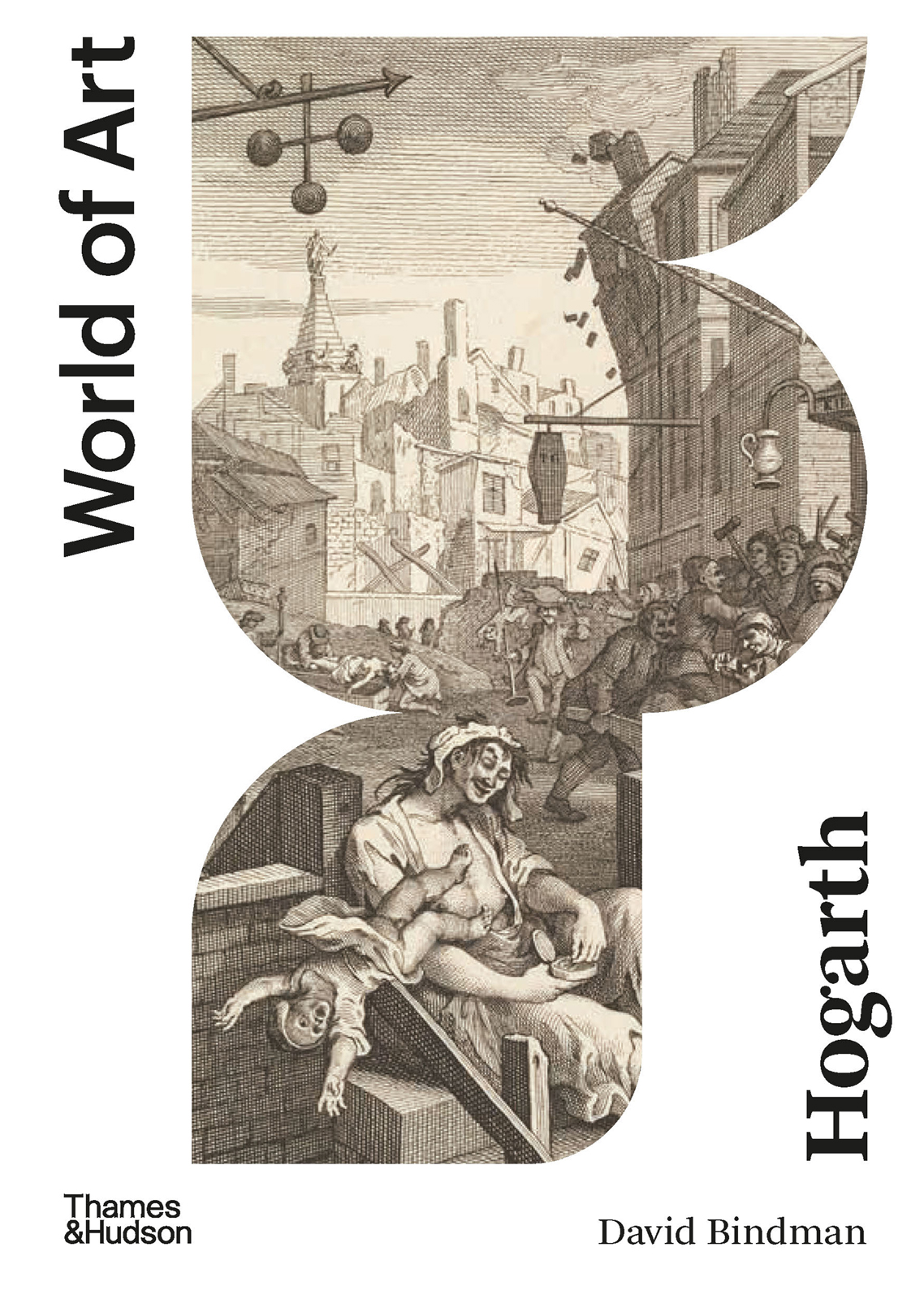

Hogarths prowess as a painter had been proclaimed in Lawrence Gowings pioneering if idiosyncratic exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 197172, but it was revealed in all its glory and context in the exhibition of 2007, curated by Mark Hallett and Christine Riding, held at the Louvre, Tate Britain and CaixaForum Madrid. Here it was possible to see Hogarth as a painter of international significance, and not just as a highly influential engraver whose motifs and characters had become international currency for artists and writers.[]

The idea of Hogarth as a European figure is not new; it had been the subject of Frederick Antals great book of 1962, Hogarth and his place in European Art, which had demonstrated that the artist was part of a broad middle-class movement that was to culminate in the 1789 French Revolution. While much work has been done in the last forty years on Hogarths London, the only book to move him fully beyond his local context has been Robin Simons Hogarth, France and British Art, of 2007, which demonstrates that despite Hogarths openly expressed contempt for all things French (after his one visit to France in 1748 he remarked Their houses are all gilt and beshit), his art was thoroughly beholden to French techniques, and he was on close terms with many in the London French community of artists and craftsmen. I am happy to say that as this book appears an exhibition is opening at Tate Britain on the very subject of Hogarth and Europe.

What have I learned about Hogarth in the last forty years? An exhibition that I curated at the British Museum in 1997 to commemorate three hundred years since his birth, because it was largely concerned with his engravings and their context, led me to delve much more into Hogarths role as a satirist in London in the period from the 1720s to the 1760s. It confirmed to me that a number of fictions had become attached to Hogarth, in some cases since the eighteenth century, that gave a completely false and sometimes anachronistic view of his character and attitudes. The main and most persistent one is that he was an honest outsider shocked to the core by the corruption of the aristocracy and those who pretended to that class, and that his engraved series are a heroic condemnation of the Establishment of the day. Far from being the Che Guevara of Covent Garden, he was on the best of terms with dukes, earls and politicians, most of whom admired him greatly. He ended his life not as a political rebel but as a courtier to George III defending the notorious Earl of Bute, to the open disgust of John Wilkes, who was a real radical. Not that his courtly standing gave him any happiness; he still died resentful and embittered at the state of the world.

The other thing I have had confirmed over the years, against the grain of common belief, is that Hogarth was a man of a great intellectual sophistication. His education, mostly by a father who was in debtors prison through much of his sons youth, was probably intermittent; he was never confident or polished in writing. He was in his own way as much a social climber as his Rake and Harlot, but his cast of mind is much closer to those supremely cultivated and classically learned satirists Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, who looked back to Roman antiquity for the source of their wit. It is quite clear that Hogarth was familiar with the Roman satirists, like Juvenal, though he was never part of the elevated circles of the likes of Swift and Pope, and seems to have resented his exclusion from them.

I have made a number of changes to the original text of this volume, mostly minor alterations of syntax, but I have also added a new chapter on Hogarths Africans, largely because I have in recent years been much concerned with the presence of Black people in art, but also because Hogarth himself seems to have been one of those artists particularly interested in them. I have also rearranged the order of the later chapters to improve their flow, I hope.

Since writing the preface to the first edition in 1980 I have incurred a new set of debts to people I have talked to about Hogarth and whose works I have read. Ronald Paulson has dominated the field of Hogarth studies since the mid-1960s and through his meticulous scholarship continues to do so. I offer the warmest thanks to collaborators and participants in various Hogarth projects over the years, which include the delightful experience of curating the exhibition Hogarth: Place and Progress at Sir John Soanes Museum, 201920. I would especially like to thank Brian Allen and Frdric Oge. I am also indebted to Bruce Boucher, Martin Butlin, Antony Griffiths, Mark Hallett, Patrick McCaughey, John Marciari, Sheila OConnell, Romita Ray, Jacqueline Riding, Jennifer Roberts, Duncan Robinson, the late Angela Rosenthal, Jessica Todd Smith, David Solkin, Joanna Tinworth, Diane Waggoner, Peter Wagner, Scott Wilcox and Andrew Wilton.

My biggest debt is to Frances Carey, who has been as essential to this edition as she was to the first.

Unless otherwise stated, collections are in London.

There has barely been a decade since Hogarths death over two hundred years ago in which someone has not written a book on him or gathered together a volume of his prints. By no stretch of the imagination can he be considered an unjustly neglected artist. Each generation has found its own Hogarth, and a number of studies from the 1950s to the present day, notably those by Professor Ronald Paulson, have made available an immense amount of information about his life and labours. Yet our estimate of him has undergone two major changes over the last two centuries.

Next page