Astrutting,consequentiallittleman.

BENJAMIN WEST , President of the Royal Academy

HowIwantthee,humorousHogart!

Thou,Ihear,apleasantrogueart.

WerebutyouandIacquainted,

Everymonstershouldbepainted

Drawthemsothatwemaytrace

Allthesoulineveryface.

JONATHAN SWIFT , after seeing TheRakesProgress (1736)

MypicturewasmyStageandmenandwomenmyactors

WILLIAM HOGARTH (c. 1763)

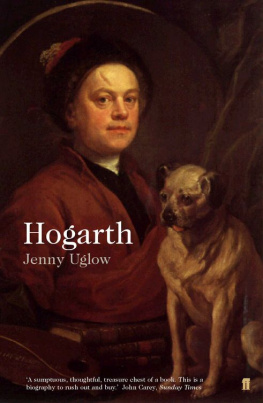

THIS IS WHAT I first loved in Hogarth. He drew ordinary, flawed people in everyday settings and told powerful stories, bawdy and violent, appealing and grim. He eyed his city, its posturing rich and flailing poor. Any day, stuck in a London queue, you can glance over your shoulder and think, My God, those faces look exactly like a Hogarth crowd. Unlike the stiff, serenely proud folk of aristocratic portraits, his men and women have squashed, pulled-about faces, big noses, straggly hair and precarious wigs; you can see how their clothes button up (or fall apart), how they take their medicine, sing, smoke, scheme and gamble and live and die. Yet although they seem solid and real, Hogarths prints are also distant and strange, and this too is part of their appeal.

Like a sharp-elbowed, awkward-angled peg, Hogarth refuses to fit neatly into any slot. He was an artist of flamboyant talent; a satirist with an unerring eye; an ambitious, pragmatic professional; a visionary who changed British art; a stubborn, difficult, comic, vulnerable man. His name conjures an epoch The Age of Hogarth, Hogarths England, Hogarths London. His daring was matched by his versatility. After the black-and-white prints, whose monochrome satire touches on cruelty, his paintings are a revelation, both in their vibrant colour and their emotional range. He painted the great and good but also the common people the middle-class wife, the merchant, the shrimp-seller, children, his servants, his friends. His portraits have the same directness as his prints, but seem the work of a painter of more delicate perceptions, in love with texture and tone and nuanced surface.

Never content, Hogarth wanted to excel at everything at engraving, at portraiture and at history-painting, highest of the arts and he couldnt, quite. As a painter he lacks the elegant clarity of Ramsay, the stateliness of Reynolds, the vivacity of Gainsboroughs brushwork. But his paintings reveal his artistry, his strong theatrical sense and brilliant formal use of space, line and colour. Here, as in the prints, he enjoys visual puns and clues. He excels at the telling detail from the small child dropping her fan in the early APerformanceofTheIndianEmperor, to the surreal cascading crockery, frozen in mid-air with the tea still spurting from the tea-pot, in AHarlotsProgress, or the brick flying through the window with an almost audible whoosh in AnElectionEntertainment.

Tables overturn, chairs balance at the moment of toppling, houses crash into the street, liquid streams from unexpected heights. That sense of risk, of aspiration and sudden, tumbling fortunes, of being pissed on from above while pits open below, is another vein threading through Hogarths work and life. As Hazlitt said, he painted no indifferent, unimpassioned pictures of humanity; he was comically rich and exuberant, carried away by a passion for the ridiculous. He did not show folly or vice

in its incipient, or dormant, or grub state; but full grown, with wings, pampered into all sorts of affectation, airy, ostentatious and extravagant. Folly is seen at the height the moon is at the full; it is the very error of our time.

Hogarth was not an isolated genius. His satire sprang from a rich graphic culture already in place in London, but he pushed its possibilities further than any of his peers. His story sequences of the Harlot and the Rake and MarriageA-la-Mode were something absolutely new, little ballad operas blending old plot lines with topical allusions, as familiar as morality plays and as fresh as the scandal in the morning papers. The satirical and the polite conduct a lively running argument in every aspect of his art. He also broke all the art-world taboos, disdaining academic divisions, turning directly to the public, cutting past the connoisseurs. Shocking his peers, he was the first artist to advertise, to shout his wares in the press, to bypass the dealers and printsellers by selling his own work. After Hogarth nothing could be quite the same. In the world of prints he was a hinge between the old popular art and the modern, easing open the door to mass production and pointing forward to the cartoonist and the modern comic strip.

Yet although Hogarth seems so open and accessible, many details of his work are elusive, full of references and jokes that his contemporaries could read in a way lost to us. And although he insisted men and women should judge with their own eyes, not according to rules, this must be set against the profound and problematic rethinking of culture and art that was taking place at the time. The more I looked at Hogarths prints and paintings, the more intrigued I became. I wanted to write about the man, but also to crack the codes and understand the different audiences he was addressing to use the voices of his own age and the rich fund of art history so that we could all read his pictures and this required a picture wider than the individual life, a broad shading of events, manners, beliefs and arguments taken for granted at the time. In the course of my quest I have often taken heart from the fact that Hogarth himself would have no truck with the idea of idle curiosity to him curiosity was active and positive, powerful and pleasurable. He gives me leave to trespass.

*

Hogarths domain was London: Smithfield, Covent Garden, Leicester Square. His precarious childhood, oddly like that of Dickens, gave him both a vivid sympathy for the poor and a fierce determination never to be one of them. His connections (and his criticisms) spread beyond London and Britain to Europe and outward to the colonies, built on slavery and convict labour. All the great arguments of his time run through his work: the nature of British liberty, the dangers of mercantilism and luxury, the duty of the rich to the poor.

He was born in 1697, in the reign of William and Mary, and died in 1764, Serjeant-Painter to the young George III. His early manhood saw the South Sea Bubble and the rise of Walpole; his final years the Seven Years War and the triumph of Pitt. He lived in a time of commercial and imperial expansion, of trade with (and wars over) India, the West Indies, North America. And if such expansion implies stability, there was also great turbulence: war abroad and riots and Jacobite rebellion at home. Thousands gathered at Tyburn on public hanging days and highwaymen were heroes. The street scenes and fairground crowds that Hogarth drew always have a hint of violence in reserve.

Yet if the early eighteenth century was greedy and cruel, with an ever widening gulf between haves and have-nots, the new polite society increasingly cultivated the cults of feeling and benevolence. As an artist, an aspiring gentleman and a sturdy patriot, Hogarth was involved with the new philanthropic movements; he was a Governor of St Bartholemews Hospital, of the Foundling Hospital and of Bedlam. His work also shares the excitement of the intellectual and scientific exploration that flowered across Europe. In his early years Newtons