Jenny Uglow - The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810

Here you can read online Jenny Uglow - The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2011, publisher: Faber & Faber, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber & Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- City:London

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

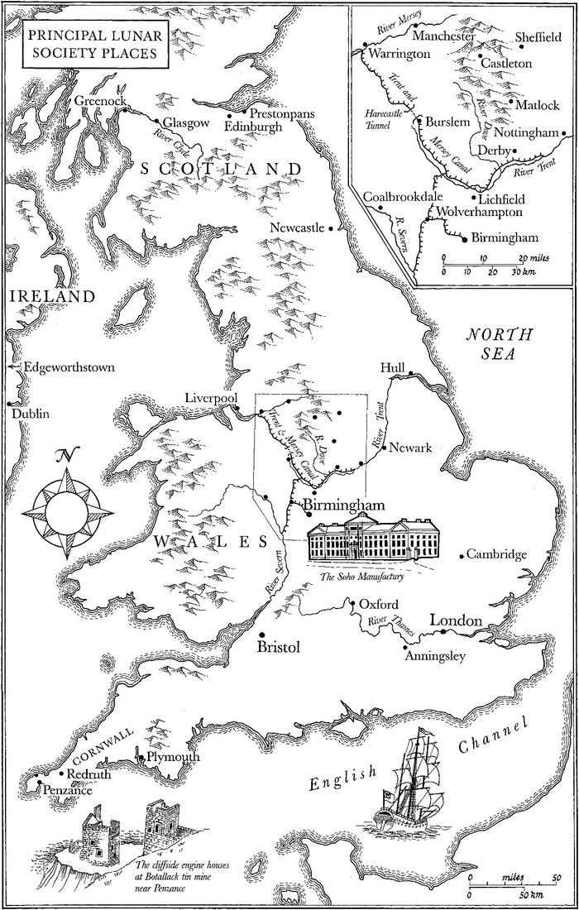

Led by Erasmus Darwin, the Lunar Society of Birmingham was formed from a group of amateur experimenters, tradesmen and artisans who met and made friends in the Midlands in the 1760s. Most came from humble families, all lived far from the centre of things, but they were young and their optimism was boundless: together they would change the world. Among them were the ambitious toy-maker Matthew Boulton and his partner James Watt, of steam-engine fame; the potter Josiah Wedgwood; the larger-than-life Erasmus Darwin, physician, poet, inventor and theorist of evolution (a forerunner of his grandson Charles Darwin). Later came Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen and fighting radical.

Led by Erasmus Darwin they joined a small band of allies, formed the Lunar Society of Birmingham (so called because it met at each full moon) and kick-started the Industrial Revolution. Blending science, art, and commerce, the Lunar Men built canals, launched balloons, named plants, gases and minerals, changed the face of England and the china in its drawing rooms, and plotted to revolutionise its soul.

Jenny Uglows TheLunar Men is a vivid and swarming group portrait that brings to life the friendships, political passions, love affairs, and love of knowledge (and power) that drove these extraordinary men. It echoes the thud of pistons and the wheeze and snort of engines, and brings to life the tradesmen, artisans, and tycoons who shaped and fired the modern age.

Winner of the PEN Hessel-Tiltman prize for history, and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for biography, The Lunar Men captures the creation of the modern world with lucid intelligence, sympathy and wisdom. Jenny Uglow is also the prize-winning author of Natures Engraver, Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories and most recently, In These Times.

**

Jenny Uglow: author's other books

Who wrote The Lunar Men: The Inventors of the Modern World, 1730–1810? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.