I shall never forget Mr Boultons expression to me: I sell here, Sir, what all the world desires to have Power.

Of peaceful houses with unquiet sounds.

There is universally something presumptuous in provincial genius.

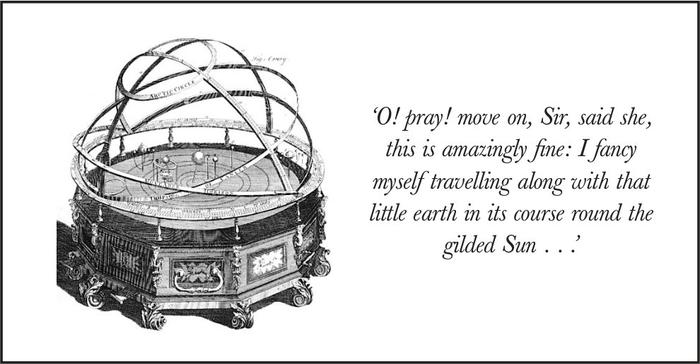

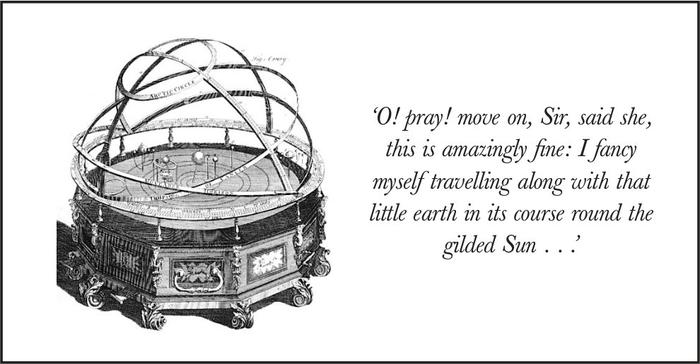

The Grand Orrery, and a quotation from John Harris, Astronomical Dialogues, 1719

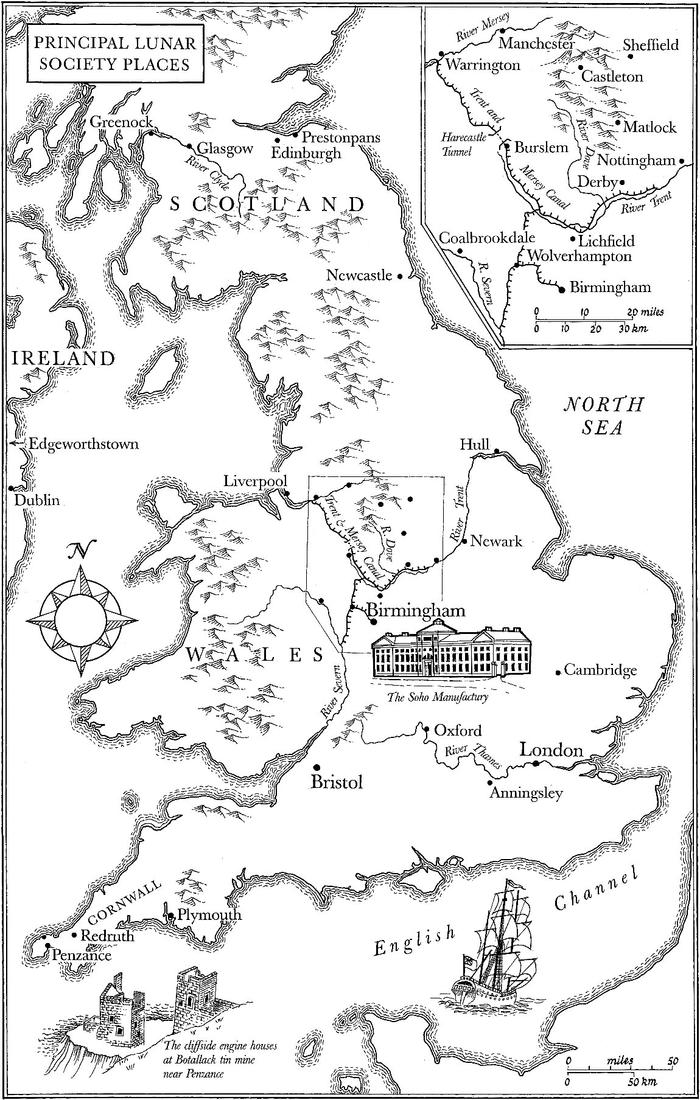

The earth turns and the curving shadow sweeps round the globe. The sun sets, the moon rises, and all that is familiar feels suddenly strange. In an age before street lights, link-boys carry torches to see city-dwellers home, while in the countryside starlight and moonlight are the only guides. The footpads are out, a darker blackness against shadow, so for safetys sake men walk together when they roll back from the coffee-house, the tavern and the club. And in the eighteenth century clubs are everywhere: clubs for singing, clubs for drinking, clubs for farting; clubs of poets and pudding-makers and politicians. One such gathering of like-minded men is the Lunar Society of Birmingham. They are a small, informal bunch who simply try to meet at each others houses on the Monday nearest the full moon, to have light to ride home (hence the name) and like other clubs they drink and laugh and argue into the night. But the Lunar men are different together they nudge their whole society and culture over the threshold of the modern, tilting it irrevocably away from old patterns of life towards the world we know today. That is why I wanted to write about them.

Amid fields and hills the Lunar men build factories, plan canals, make steam-engines thunder. They discover new gases, new minerals and new medicines and propose unsettling new ideas. They create objects of beauty and poetry of bizarre allure. They sail on the crest of the new. Yet their powerhouse of invention is not made up of aristocrats or statesmen or scholars but of provincial manufacturers, professional men and gifted amateurs friends who meet almost by accident and whose lives overlap until they die.

So who are they?

First to enter is Erasmus Darwin, doctor, inventor, poet and half a century before his grandson Charles pioneer of evolution. (Enormously gifted and enormously fat, eventually he has to cut a semi-circle in his dining table to fit his stomach.) Then comes Matthew Boulton, flamboyant chief of the first great manufactory at Soho, just outside Birmingham, followed by his anxious Scottish partner James Watt, of steam-engine fame. Another member is the ambitious young potter Josiah Wedgwood, and eventually, in 1780, Joseph Priestley arrives, the preacher with the stuttering voice and flowing pen, the chemist who isolates oxygen and becomes the visionary leader of Rational Dissent.

This quintet forms the core. But around them weave other stories, a string of names that take on shape as they turn up in their top-coats and breeches, driving newfangled carriages, talking of freedom, of riots and reform, love and laughing-gas. Among them are the Scots chemist James Keir, reliable as a rock; the clockmaker John Whitehurst, who works with minutes but dreams of millennia, the age of the earth itself. Then come the doctors: the diplomatic William Small who seals their early friendships, and the austere William Withering, who brings digitalis into mainstream medicine. And a wilder note sounds with the arrival of two young, idealistic followers of Rousseau, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Thomas Day.

Ten of these men became Fellows of the Royal Society but only a few had a university education and most were Nonconformists or freethinkers. This placed them outside the Establishment an apparent disadvantage which proved a real strength, since they were unhampered by old traditions of deference and stuffy institutions. They came from varied backgrounds but when they edged towards rows they agreed to differ, turning back to the things they shared. We had nothing to do with the religious or political principles of each other, wrote Priestley. We were united by a common love of science, which we thought sufficient to bring together persons of all distinctions, Christians, Jews, Mohametans, and Heathens, Monarchists and Republicans. impasse. Their passionate common exchange and endeavour was of a type that would never be possible again until today, with the fast, collaborative intimacy of the Internet.

To begin with they came together simply through the pleasure of playing with experiments, what Darwin called a little philosophical laughing. At other times, the whole of the natural world suddenly became collectible, as if knowledge were conveyed directly, visibly, tangibly by the objects in a cabinet of curiosities. When Peter the Great asked the philosopher Leibniz in 1708 what he should collect, the answer, it seemed, was everything:

Such a cabinet should contain all significant things and rarities created by nature and man. Particularly needed are stones, metals, minerals, wild plants, and their artificial copies, animals both stuffed and preserved Foreign works to be acquired should include diverse books, instruments, curiosities and rarities In short, all that could enlighten and please the eye.

However, Peters daughter-in-law Catherine the Great (another great collector) disparaged this old, baroque style of freakish accretion: I often quarrelled with him, she wrote, about his wish to enclose Nature in a cabinet even a huge palace could not hold Her.

Nature would not be confined. In the mid-eighteenth century, across Europe, in Britain and in America, ordering the vast and complex riches of Nature became a priority. This was the age of great scientific expeditions. When the naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander travelled with Captain Cook on his voyage to the South Seas from 1768 to 1771, they brought back 1,000 new species of plants, 500 fish, 500 bird skins, numberless insects and hundreds of drawings. It was against this background that Erasmus Darwin translated Linnaeus, wrote his epic poem The Botanic Garden and developed his own controversial theories of evolution.

In exploring such matters Darwin and his friends were part of the great spread of interest in science that extended from the King and the Royal Society to country clergymen and cotton-spinners. When people talk of eighteenth-century culture this is the swathe that is often missed out: the smart crowds thronging to electrical demonstrations; the squires fussing over rainfall gauges; the duchesses collecting shells and the boys making fire-balloons; the mothers teaching their children from the new encyclopaedias with their marvellous engraved plates of strange animals and birds and plants.