Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR HERMIONE AND JOHN

CONTENTS

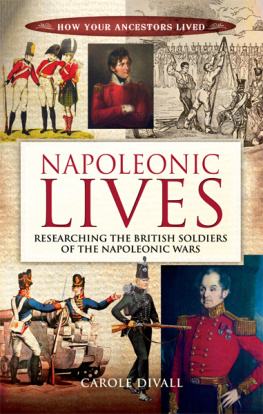

The cathedral city of Canterbury had a barracks on the downs nearby until it closed, when the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders left, in March 2013. In the last fifty years soldiers have gone from here to the Falklands, the Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan. This is my home town and I have seen feelings veer over time from antipathy squaddies barred from pubs to respect and sympathy help for heroes and back to suspicion again. One does wonder, though, why they joined the army in the first place? asked a woman, looking sideways at me on the bus. Not so different then, from the way people spoke about Wellingtons scum of the earth, the heroes of the Peninsular War. The first barracks here were built for them in Military Road by a young speculator of dubious reputation. He made a fortune.

In the twenty-two years from 1793 to 1815, with a brief gap in 18023, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars touched people in every part of Britain. Boys who were babies when the wars began fought in the Peninsula and at Waterloo. Because of the way recruiting and balloting were organised, every village, every hundred, had to list its men, and men from one in five families were directly involved, in the army and navy, the militia and volunteers. As the years passed, so the bullish, flamboyant figure of Napoleon came to dominate so strongly that the whole conflict was given his name and Boney became the bogeyman of childrens nightmares. The period has been labelled in different ways the Romantic Era, the Age of Wonder, the Age of Scandal, the Age of Cant yet behind all those lay a country at war. And as I thought about the men who marched away I began to wonder, how did the wars affect the lives of people in Britain, not those who fought, but those at home looking on, waiting, working, watching?

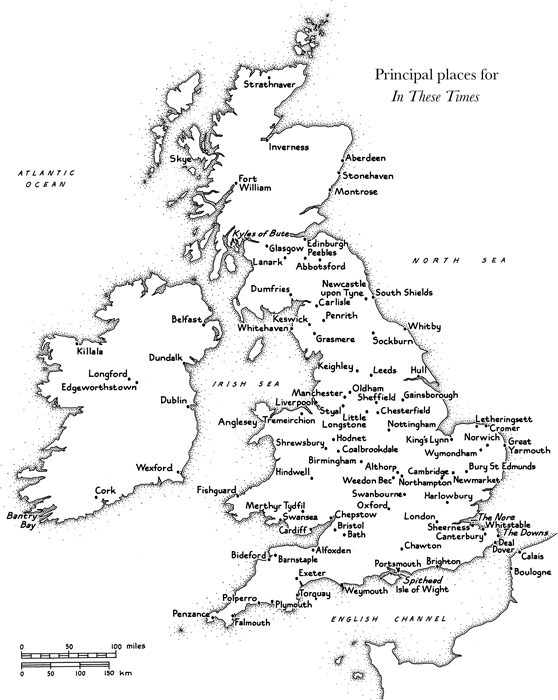

This book is an attempt to pursue that question by following a few people and families. It is a cavalcade with a host of actors a crowd biography, if such a thing is possible. It moves from fields and farms to dockyards and foundries, theatres and fairs, drawing rooms and clubs. It follows the back and forth of war and domestic politics, seeing how news reached the people, how fear bred suspicion and propaganda fuelled patriotism, how victories were celebrated and the dead were mourned, how some became rich and others starved. The big names are here Pitt, Fox, Nelson, Wellington, Wilberforce and others but history is not a matter of individual lives, however powerful or heroic. It is multi-layered, with many facets. At some times in this story conflict at home seems more pressing than battles abroad, with the state silencing free speech, spies sending reports, the militia firing on crowds. In Ireland that conflict was deadly. For some people the reports and rumours of victories and defeats and the accounts of Napoleons lightning marches were like a huge running serial that they could not get enough of. For others they were a muddle of confused events in places with difficult foreign names, humming in the background, slipping off the side of the page. The wars were like permanent bad weather, so all-surrounding that people stopped referring to them and merely said in these dismal times, in such troubling and dangerous times or simply in these times. They affected everyone, sometimes directly, and sometimes almost without their knowing it, and in the process the underlying structures of British society ground against each other and slowly shifted, like the invisible movement of tectonic plates.

To sketch the bigger picture, the telling swerves from general to particular, from the state of the wool trade or the action of a military campaign to a man tilling a field, a woman sitting on the stairs. And although the wars and the political disputes are areas of collective action regiments and crews, parties, crowds and mobs the detail of those lives also suggests how separate our lives are, even when we call ourselves a nation. What has a widow tramping to see a wounded son to do with a countess gambling in St Jamess? How does a south Wales ironworker connect with a country banker, or an elderly clergyman in his study? What world do they share?

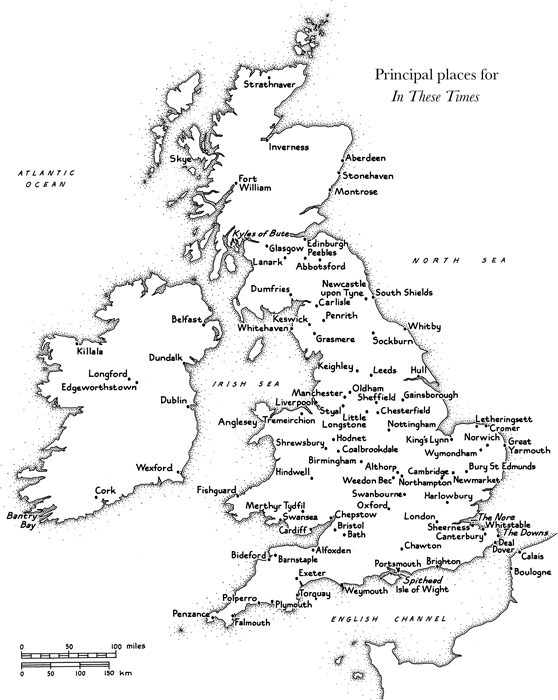

The war rumbles beneath the late poems of Burns, and colours the work of Scott, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Lamb, Clare, Byron and Shelley; it affects Maria Edgeworth and Jane Austen; it prompts moral outpourings from Hannah More and angry articles from Cobbett and Leigh Hunt; it inspires paintings by de Loutherbourg and Turner. The prints of Gillray, Rowlandson, the Cruikshanks and fellow satirists are a version of the history in themselves, biased and brilliant. These names have endured. But men and women of all classes wrote letters, diaries and memoirs. And many thousands, from women applying for parish relief to relatives looking for places for war orphans, left no record but signed their name only with a cross, on documents still in the archives. Among the crowds, here are some of the voices in this book:

The Heber family of Shropshire and London, clergymen and bibliophiles

William Harness, soldier, and his wife Bessy

James Oakes, prosperous citizen of Bury St Edmunds

The Gurney family, Norwich bankers with many children and cousins

Samuel and Hannah Greg, of Quarry Bank Mill in Lancashire

The Hoare family, private bankers in Fleet Street

The Galton family, gunsmiths of Birmingham

William Rowbottom, Oldham weaver

Boys: Samuel Bamford from Manchester, William Lovett from Penzance, Thomas Cooper from Gainsborough, future Chartist writers and leaders

John Marshall, linen-mill owner from Leeds

Aristocrats: Amabel Hume-Campbell, Countess de Grey, and her friend Agneta Yorke; Lady Jerningham and her daughter Charlotte; Sarah Spencer, later Lady Lyttelton

Betsey Fremantle and her sister Eugenia Wynne

Mary Hardy, from a Norfolk brewing family

Farmers: James Badenach of Aberdeen, Randall Burroughes from Suffolk, William Barnard of Essex

Robert Pilkington of the arms depot at Weedon Bec, Northamptonshire

Sailors: Jane Austens sailor brothers Francis and Charles; Lieutenant Thomas Gill; the Scottish seamen, John Nicol and Robert Hay

William Salmon, a young merchant mariner from the Bristol Channel

Thomas Perronet Thompson from Hull, soldier, briefly Governor of Sierra Leone

The Hutchinson family, farmers from County Durham, and their cousins the Monkhouses from Cumberland

The Longsdon family, farmers and textile merchants from Derbyshire

James Weatherley, factory boy in Manchester