PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by Allen Lane 2013

Published in Penguin Books 2014

Copyright Vic Gatrell, 2013

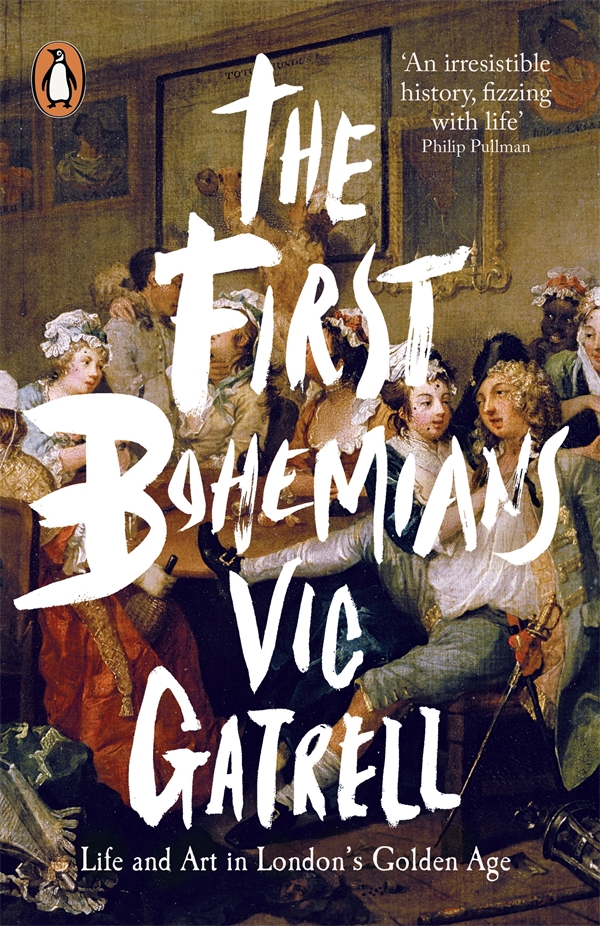

Cover image: The Rake at the Rose-Tavern, from A Rakes Progress by William Hogarth, 1733. Courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soanes Museum, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

ISBN: 978-0-718-19582-3

Contents

Foreword

For reading and commenting on parts of what follows my thanks go to good friends: Bernard Barker, Vyvyen Brendon, Lizzie Collingham, Roger Court and Jerry White. I especially thank Jeremy Krikler, who argued hard and positively about my early drafts. To the support given over the years by Sheila OConnell of the Prints and Drawings Department of the British Museum I have owed more than I can say. For encouragement, thanks too to Gill Coleridge, my agent, and Simon Winder, my editor. He and Marina Kemp have been unfailingly helpful to the book. Bela Cunha has been a copy-editor blessed with a superhuman tolerance of my inefficiencies: her patience and skill are marvellous. The cost of buying illustrations and permissions has been generously supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art (London); my college, Gonville and Caius, has kindly helped too. As ever, Pam my wife has been guide, mentor and friend sine qua non. Our beautiful grandchildren, Freya, Harry and Jack, have entered the world while the book was in the writing. I dedicate it to them and their lovely parents, Alex, Anna, Emily and Matt.

Broad social histories of eighteenth-century art like the one that follows have been hugely helped by the wholesale digitization of historical images in the past dozen or so years. In the first stages of my earlier work on eighteenth-century caricature (City of Laughter), I had myself, inexpertly, to photograph several hundred satirical prints merely to get a preliminary measure of the subject. Today the British Museum offers a couple of million downloadable images that include the bulk of its eighteenth-century prints, drawings and watercolours. It allows their free reproduction in scholarly publications, while the Mellon Center for the Study of British Art at Yale allows the free reproduction of its collection without restriction. Other libraries and museums have put their holdings on line too, though in the UK their charges can be extortionate. At any rate, one can now survey large artistic panoramas in ways hitherto unthinkable. It is possible to cut free from that well-bred connoisseurial interest in great painting and its influences that stultified much of what passed as art history in the past century, and instead as this book does to attend to the material, social and topographical conditions under which artists worked, the richness of low art forms, and the earthy rumbustious cultures that produced them.

Introduction

What kind of a history this is;

what it is like, and what it is not like

The chapter heading cited above comes from Henry Fieldings novel Tom Jones, and the fact that it was written in his sisters house in Old Boswell Court, a few minutes walk from Londons Covent Garden, makes it both topical and apt in this book. It also propels us niftily to the point, as no-nonsense eighteenth-century writing was so good at doing. The kind of history that follows concerns the territory around Covent Garden that in the eighteenth century accommodated what may fairly be called the worlds first creative bohemia. It tackles the flowering there of art forms that depicted or commented on real life, and it explores what that art tells us about some of the more significant expressions of Georgian culture, about its artists, and about London itself.

To talk of London as if it were a unity is to forget the intense localism of the lives lived there. Communities and localities have always mattered in Londons history, so that to understand its cultural energies in the eighteenth century one must become intimate with its most creative territory. Its an extraordinary fact that by far the majority of eighteenth-century British painters and engravers, as well as most noted writers, poets, actors and dramatists, lived in the square quarter-mile or so around Covent Gardens Piazza. Victorians liked to say that more people of genius were buried in the Piazzas church of St Pauls than in any other church except Westminster Abbey. This list of Covent Gardens eighteenth-century luminaries, artists, actors and actresses is typical of those that Victorians remembered, and it is far from complete:

Butler, Addison, Sir Richard Steele, Otway, Dryden, Pope, Warburton, Cibber, Fielding, Churchill, Bolingbroke and Dr Samuel Johnson; Rich, Woodward, Booth, Wilkes, Garrick and Macklin; Kitty Clive, Peg

What contemporaries called the Town had developed between the City of London and the City of Westmister in the seventeenth century. With the Piazza at its centre (), it stretched from Soho and Leicester Fields (now Square) to Drury Lane in the east, and from St Giless and Long Acre in the north to Charing Cross and the Strand in the south. It had important outreaches eastwards along Fleet Street and into the booksellers quarter of St Pauls Churchyard, but you could walk across its core in ten or fifteen minutes. Why did so many creative people flock there, and what might that have meant for the making of English art and letters? To find the answer, Part I of the book explores the district closely both its finer streets and its grimmer back alleys and the poor people who lived in them. The district could be as polished a place as any in England, but also as rough. Both qualities influenced the subject-matter of the pictures, books and plays that were produced there.