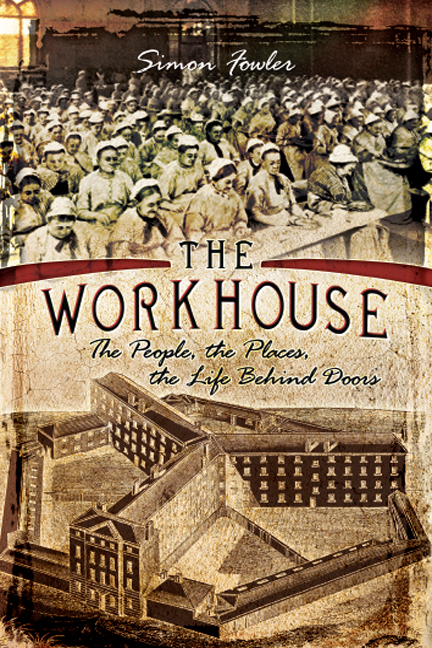

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Simon Fowler 2014

ISBN 978 1 78383 151 7

eISBN 9781473840843

The right of Simon Fowler to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Jen Newby at Pen & Sword for agreeing to publish a revised edition of this book and her colleagues for seeing through the press. At The National Archives Laura Simpson graciously allowed me the rights to the book and Catherine Bradley originally commissioned the book. Janet Sacks edited a somewhat unwieldy text and her comments still challenged when it came to the revision.

And lastly, but above all others, Sylvia Levi who did more, much more, than could have been expected of any authors wife as chauffeur, researcher and slave-driver.

Errors and omissions are, of course, my own.

Preface

W hen people of my parents generation were growing up, they were often threatened with the workhouse for being wasteful or profligate with precious resources, even for eating a slice of bread too many. It was a largely a reflex action but for my grandparents, and particularly for their parents, the workhouse and the world of the Poor Law was one that they strenuously and, so far as I know, successfully avoided. This book is an attempt to find out why they had that reaction.

The workhouse still has the capacity to shock. One of the most popular ITV programmes of 2013 was Secrets of the Workhouse in which half a dozen celebrities, such as Fern Britton, Felicity Kendal and Brian Cox, researched their ancestors who had spent time in the workhouse. As in the tradition of such programmes, tears were to the fore and the horrors inevitably played up. According to the press pack which accompanied the show: With no benefits system in place, destitute people were either left to starve on the streets or forced to submit themselves to the harsh conditions of the workhouse where they worked ten hours a day doing menial tasks such as breaking rocks up or picking apart ropes.

In books a surprising bestseller in recent years has been Jennifer Worths Shadows of the Workhouse , in which she shows how the long shadow of the workhouse and the relieving officer still affected the lives of the residents of Poplar in the years after the Second World War. Reviews emphasised the harrowing nature of much of the book, but also that Worth stressed that the alternatives were often little better.

The temptation for writers and directors is to show the workhouse as being unremittingly Oliver Twist grim, ideally with a celebrity in tears as they discover the true horrors of the Poor Law system. Memorably this was the case with Jeremy Paxman in an early series of Who Do You Think You Are? , when he broke down after discovering how his great-grandmother Mary was offered the workhouse after giving birth to an illegitimate daughter: She committed the great sin of having a child and was faced with the decision to keep her family together and risk starvation or split them up and live in a dreaded workhouse. She chose to stay with her children, and I admire her decision.

The truth, as this book will show, is more nuanced. In her review of the Secrets of the Workhouse TV programmes, Swansea University historian Lesley Hulonce commented:

To borrow a phrase from peerless John Motson this programme was indeed a game of two halves. One half saw leading historians such as David Green, Elizabeth Hurran and Allannah Tomkins offering articulate and knowledgeable commentary which was often bowdlerised by narration provided by Mr Carson, the butler from Downton Abbey (Jim Carter), whose script oscillated between reasonable historical rationalisations and rather hysterical (and often untrue) pronouncements.

Many people learn about the workhouse at school or by visiting museums. The scandal at Andover Workhouse in 1845, where starving paupers were forced to eat the marrow from the bones they were meant to be crushing, shocks modern students just as it did the readers of the newspapers in which each revelation was covered in lurid detail. But was every workhouse as bad? In these sentimental days the paupers who ground the bones are presented as the innocent victims of a cruel and misguided policy, forced into dreadful workhouses where the children were beaten and their parents neglected. Is this really the case?

One thing is clear from any study of welfare history, that, although the terminology changes, the problems and the solutions largely remain the same. Basically, how do you match up limited resources with the desire to help fellow citizens in need? How generous do you make the support offered to the destitute, the aged and the infirm? If it is too generous, then the taxpayer will complain of the financial burden and you risk the possibility of welfare dependency, that is people preferring to remain on financial support rather than find a job.

In the 1820s theorists, such as Revd J. T. Becher who was behind the establishment of what became the Southwell Workhouse near Nottingham, argued that workhouses would encourage the poor to stand on their own two feet. In words not dissimilar to those coming from the mouths of welfare reformers today, Becher wrote:

Let it be remembered that the advantages resulting from a workhouse must arise not from keeping the poor in the house, but from keeping them out of it, by constraining the inferior classes to know and feel how demoralising and degrading is the compulsory relief drawn from the parish to silence the clamour and to satisfy the cravings of the wilful and woeful indigent: but how sweet and wholesome is that food and how honourable is that independence, which is earned by perseverance and honest industry.

Conversely, if the financial support is not generous enough then the genuinely deserving will suffer and there will be scandals, and possibly even protests from claimants. There are striking parallels with scandals in social services and the National Health Service today. The Mid Staffordshire Hospital scandal between 2007 and 2009 could easily have occurred in workhouses 150 years ago. An inquiry led by Robert Francis found, A chronic shortage of staff, particularly nursing staff, was largely responsible for the substandard care. In addition, morale was low and while many staff did their best in difficult circumstances, others showed a disturbing lack of compassion towards their patients. In 1867 Matilda Beeton, a nurse at Rotherhithe Workhouse told an inquiry that: On the whole it did not seem to me that a paupers life was regarded in any other light than the sooner they were dead the better.