CONTENTS

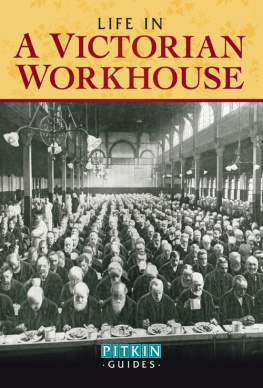

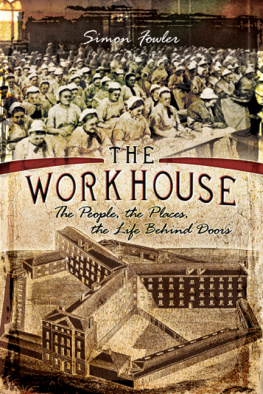

Workhouses never had a good image. From the seventeenth century, when the earliest such institutions appeared, until the inauguration of Britains National Health Service in 1948, which is often taken as the date of their final demise, workhouses were regularly painted as places of shame, abuse, degradation, slavery, cruelty, disease, squalor, and due in no small part to a certain Oliver Twist of starvation.

For most decent people, the possibility of ending up in a workhouse carried an enormous stigma. For one thing, it would be a very public humiliation everyone would be aware of where they had gone. On top of that, there was the sheer unpleasantness of the whole experience the separation of families, the monotony of the food, the uniform and, for the able-bodied at least, the daily grind of workhouse labour. For the elderly, the prospect of dying in a workhouse held out the grim possibility of a paupers funeral in an unmarked grave or, even worse, being despatched for anatomical dissection.

But were things really that bad? From the 1870s onwards, many aspects of workhouse life materially improved. Inmates increasingly benefited from better medical care, more varied and better quality food, and better recreational facilities in the shape of books, newspapers, entertainments, and outings to the country or seaside. The elderly, in particular, received extra indulgences such as weekly allowances of tea, tobacco and snuff.

Despite such changes, the workhouse remained a place that many people would rather die than go into. Over the years, as illustrated in the pages of this book, numerous examples can be found of individuals taking their own life rather than enter the workhouse. (In one case at least, though, a suicide resulted from an individual not being allowed entry to a workhouse.) Suicides also regularly took place amongst those who were already workhouse inmates, the most favoured methods being throat-cutting, hanging, taking poison, or jumping from a high window.

Even for those who reconciled themselves to institutional life, the workhouse could be a dangerous place. There could be violence sometimes with fatal consequences between inmate and inmate, inmates and staff, or between members of staff themselves. Some of the most disturbing events in the history of the workhouse, though, occurred where those in positions of authority and control inflicted abuse or neglect on those in their care, sometimes for years on end before being discovered. Some of these individuals, most notably the tyrannical workhouse masters George Catch and Colin McDougal, and the sadistic childrens nurse Ella Gillespie, have now become infamous for the vileness of their activities.

For all workhouse inmates, though, life could hold unexpected perils. As this almanac reveals, even apparently innocuous activities such as eating dinner, having a bath, paying a visit to the toilet, sitting in front of the fire, or even lying asleep in bed could all turn into life-threatening situations. The medical care provided to inmates, too, could sometimes have perilous consequences. The accidental or inept administering of injurious treatments to workhouse patients was the cause of a number of deaths, including that of a workhouse master who had devised and himself tried out a particularly poisonous concoction. The occasional mind-numbing foolishness of staff is also evidenced in more than one instance when the investigation of a gas leak was conducted with a lighted candle or lantern.

The outbreak of fire was a danger in all large institutions, especially ones such as workhouses where children, the elderly, and the mentally impaired formed a large proportion of the inmates. Some of the most harrowing scenes described in this volume were the devastating results of fires which proved too intense for the facilities available to fight them or where defects in the buildings prevented the evacuation of those inside.

Despite such hazards, longevity was surprisingly common amongst workhouse inmates, with the remarkable age of 136 years being claimed in one instance. Romance, too, was not unknown in the workhouse. Despite the enforced separation between male and female inmates, love could find a way as proved in a number of instances. Given the constrained lives imposed on workhouse employees, it is also not surprising that relationships between staff blossomed from time to time. There are even instances of staff and inmates falling for one another.

Workhouse inmates were not, of course, just passive recipients of poor relief. They knew how to play the system. Whether it was harbouring secret stashes of money, illicitly consorting with the opposite sex, smuggling alcohol or drugs into the premises via visitors or the informally appointed inmates messenger, or even in the case of at least one elderly couple getting married in order to benefit, it was alleged, from the provision of their own private room.

Although most of the events related in this book took place in the British Isles, a few are included from other countries around the world which operated workhouse-style institutions, including the United States, Russia, Sweden and Czechoslovakia. Inevitably, to rate as newsworthy in Britain, such incidents were generally major disasters such as devastating fires. An index of all the workhouse locations mentioned is included at the end of the book.

Finally, to keep the many grim events presented here in perspective, it must be remembered that under the new poor relief system established in 1834, there were more than 600 union workhouses set up in England and Wales. For most of these establishments, scandal or catastrophe was a rarity perhaps occurring just once or twice over the century or so of their existence. For the vast majority of their lifetime, they just got on and did their job.

This book does not aim to be a comprehensive history of the workhouse system. However, for those not familiar with its development, here is a timeline of some major events:

1601 | The Poor Relief Act is the basis of what becomes known as the Old Poor Law. Parishes become responsible for relieving their own poor funded by a local property tax the poor rate. The poor rate can be spent on out-relief (handouts to individuals) or accommodation for the impotent poor the elderly, lame or blind. |

1630s | Workhouses gradually evolve to house the poor, with labour required from the able-bodied. Prototype workhouses include Reading, Abingdon, Sheffield, Newark and Newbury. |

1698 | Bristols parishes promote a local Act of Parliament allowing them to jointly administer poor relief and run workhouses. |

1723 | Knatchbulls Act allows parishes to establish workhouses. Parishes can dispense with out-relief and offer relief claimants only the workhouse a test that they are truly destitute. Workhouse operation can be handed over to private contractors, the practice becoming known as farming the poor. |

1777 | Around 2,000 workhouses are in operation, covering about 14 per cent of parishes. Out-relief is still the dominant form of provision, however. |

1782 | Gilberts Act allows groups of parishes to form unions and run joint workhouses to house non-able-bodied paupers. |

1818 | The national poor relief bill reaches an all-time high, having risen fivefold over the previous forty years. |

1834 | The Poor Law Amendment Act (the New Poor Law) establishes a new national system of poor relief administration, run by the central Poor Law Commissioners, based on groupings of parishes called Poor Law Unions. Each union is run by a locally elected Board of Guardians and has to provide a central union workhouse. |

Next page