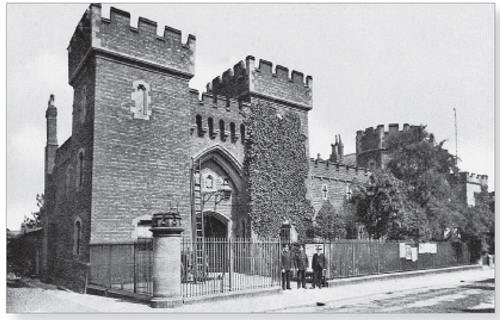

Winson Green Prison. (Authors collection)

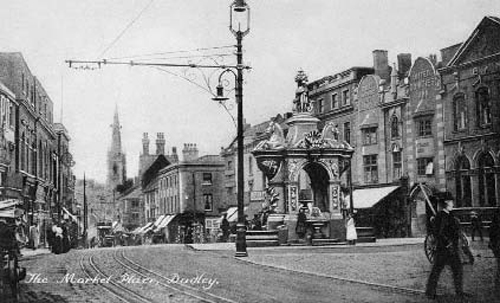

The Market Place, Dudley. (Authors collection)

CONTENTS

The first obstacle in writing about the Black Country is determining exactly where it is, since its location is not precisely defined. For example, some would argue that it doesnt include Wolverhampton, Smethwick or Stourbridge, while others say that it is anywhere within the Metropolitan District Council areas of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton. I sincerely hope that I havent taken too many liberties with the geography of the area.

All of the stories within this book are true and were sourced entirely from the contemporary newspapers listed in the bibliography at the rear. However, much as today, not everything was reported accurately and there were frequent discrepancies between publications, with differing dates and variations in names and spelling.

As always, there are a number of people to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their assistance. Dennis Neale, who runs a fascinating website called Black Country Muse, was extremely helpful and knowledgeable and very kindly gave me permission to use one of his illustrations, as did the Wolverhampton Express and Star , who permitted me to use their illustrations pertaining to the Hagley Bella case. On a personal level, my husband Richard provided constructive criticism and countless cups of tea! I would also like to thank Matilda Richards, my editor at The History Press, for her help and encouragement in bringing this book to print.

Every effort has been made to clear copyright; however, my apologies to anyone I may have inadvertently missed. I can assure you it was not deliberate but an oversight on my part.

Nicola Sly, 2013

Dudley police station. (Authors collection)

1 JANUARY

1869 Schoolmistress Elizabeth Fereday faced magistrates at Wolverhampton Police Court charged with assaulting a pupil. Eight-year-old Nancy Ann Joness parents complained that, just before Christmas, Mrs Fereday had struck their daughter in the face with a cane. Nancy was brought into court still sporting a black eye, and the Magistrates Clerk testified that the bruising had been much worse when the summons against the teacher was taken out soon after the incident.

Mrs Fereday denied hitting Nancy, saying that the child was injured by falling onto a bench. She claimed that Nancy was impudent and refused to do her school work, prompting her to tell the girl that she would not be spoken to in that way. Mrs Fereday said that she was about to box the childs ears when Nancy accidentally fell and hit her face.

The magistrates found in Nancys favour, fining Mrs Fereday 2 plus costs.

2 JANUARY

1889 Richard Walters and Fanny Cornock left home to go for a walk and never returned. The following morning, a walking stick and a womans muff were found lying on the towpath of the canal at Nine Locks, Brierley Hill.

When the canal was dragged, the bodies of twenty-six-year-old Walters and his nineteen-year-old fiance were found a few yards apart. An inquest held by coroner Mr E.B. Thorneycroft on 5 January surmised that the couple had accidentally walked into the canal during a thick fog, and the jury returned two verdicts of accidental death.

3 JANUARY

1884 Twenty-one-year-old Eliza Cartwright from Bradley felt safe walking to work, until she noticed a man crawling towards her across a field on his hands and knees. She was forced to ask for protection from a couple of men in front of her, and from that day onwards, she changed her route to one that was less isolated.

On 3 January, a postman heard a woman shouting and, moments later, he came across Eliza lying senseless on the ground. She died that evening from a compound fracture of the skull. A search of the area where she was found suggested that a great struggle had taken place and the police found two large pieces of furnace cinder, one covered in clotted blood and hair, the other tied with half of Elizas work apron.

An inquest was opened and adjourned to allow the police time to investigate. However, when the inquest finally concluded, the police were no nearer to finding Elizas killer(s) and the jurys verdict was murder by person or persons unknown.

Several arrests were made but everyone was released due to lack of evidence. Eliza had not been robbed, nor sexually assaulted and whoever killed her struck entirely at random, using the first thing that came to hand rather than a specific weapon. A reward of 100 was offered for information leading to the apprehension of her killer(s) but it went unclaimed and Elizas murder remains unsolved.

4 JANUARY

1917 Tramcar driver Richard Davies was a few minutes early arriving at the terminus at the top of Tipton Road, Dudley. He left his tram briefly and, while he was away, conductress Maggie Jefferson reversed the pole used to conduct live electricity to the controls and boarded the tram. Unaware that Davies was not in his seat, Miss Jefferson then released the brake. The runaway tram careered down Tipton Road, gathering speed as it went, and when it reached a bend, it jumped the rails and overturned.

Twenty-five passengers were injured, most of them crushed or cut by flying glass. Annie Payne was trapped beneath the rear of the tram and it took some time to free her. She was eventually lifted through a window by a nurse and doctor, but was so badly injured that she died shortly after admission to hospital.

The accident was unusual in that it replicated almost exactly another fatal accident that occurred at the same spot a year earlier in each case, even the tramcar was the same.

5 JANUARY

1894 Robert and Mary Goodwin appeared at the Guildhall in Walsall charged with neglecting their five children. Magistrates were told that the children came to the attention of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in August 1893, when the societys inspector had visited their home seven times, each time finding the children dirty, hungry and inadequately clothed.

The chief magistrate called it an abominable case but his colleague, former mayor, Mr J. Wheway, seemed fixated on whether the inspector had the right to enter the Goodwins house.

Even a poor mans house is his castle, or ought to be, insisted Wheway, who seemed unable to grasp the inspectors repeated assertions that he had permission to go in. It is not right to examine a mans rooms persisted Wheway, adding, I would not allow it in my own house and will not suffer it in anybody elses.

Although his colleagues on the Bench voiced their disagreement, Wheway continued to object, even though the societys solicitor tried to reason with him, reiterating that permission was always obtained and pointing out that it would be very difficult to prove a case of neglect or cruelty if a house was not entered. Eventually, in the face of Wheways nit-picking, the case collapsed and all the society could do was to watch the Goodwins carefully, to see how things progressed. The societys solicitor sarcastically promised that they would endeavour to do so in a manner to which Wheway could not possibly object.

Next page