CONTENTS

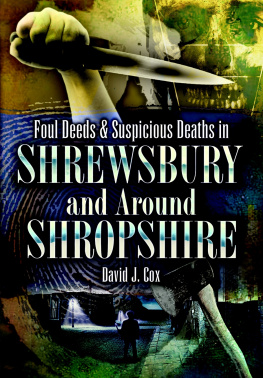

Despite the murders, the suicides, the thefts and the accidents, compiling this book has been an incredible experience. I would like to thank my editor, Matilda Richards, for giving me this opportunity and for her patience and assistance. For their constant help, I would like to thank the staff at Shropshire Archives and the contributors to the online Shrewsbury Forum. I would also like to thank my partner Simon Halse for his support and, more importantly, for all the coffee. Finally, I would love to thank my amazing parents, Alex and Judy Lyon, for introducing me to Shropshire and for their constant encouragement.

The events and information collected and revealed in the following pages were compiled from a combination of newspaper archives, websites and books. As I was conducting this research I developed a new and ardent appreciation for the information age, as well as an incredible respect for anyone who had to conduct research before the advent of the internet. Without my aging laptop and my temperamental internet connection, I would have been completely lost.

When I was first given this exciting project, a fair number of people expressed doubts that peaceable old Shropshire possessed enough of a grim history to fill the pages. I disagreed, knowing that I had the freedom to look centuries into the past but at the time I didnt entirely appreciate the amount of depravity and wickedness that Shropshire has witnessed. Research would soon reveal the hidden history of terrible crimes and unfortunate accidents which transpired in a county that, at first, seems to be so safe and friendly. It is now entirely clear that scenic views and relaxing country lanes can prove a perfect cover in exactly the same way that winning smiles can conceal a naughty childs misdeed.

Considering the unpleasant events that the research trudged up, it is strange how much I enjoyed the entire process. However, there was one thing that caused a certain amount of frustration: discovering a perfectly morbid and macabre event, only to find that there was no specific date that could be attributed to it. As you can imagine, words like approximately or circa were the bane of my existence and of no help at all when your job is to assign to each occurrence a specific date.

Some of the incidents are immeasurably cruel, some less so, and a few are almost amusing (in a sinister sort of way). It has become apparent that far more information exists regarding murders or attempted murders than about any other type of crime. Throughout history, our newspapers have been crammed full with every available gory detail, from the act itself through to the sentencing. The public has always been captivated by murder, and it isnt a preoccupation that has abated over time. Perhaps we will always possess a morbid fascination with human cruelty, as it goes so far against the social norms we live by and the values most of us revere. Many cases presented here defy belief, and in most the motive falls far short of being satisfactory.

Following a guilty verdict, a myriad of punishments were available. For the more serious crimes, such as murder or rape, hanging was the favoured form of retribution. The justification behind capital punishment stretches far back into history and is based somewhat on the biblical concept of an eye for an eye. It was thought and is still thought, by some that such a sentence would act as a deterrent, preventing similar future offences, though this argument often provokes heated debate. Hangings were also frequently doled out for crimes we would now consider extremely minor, such as the theft of a cow or sheep. Once upon a time people regularly risked their lives for a sheep or two, perhaps proving that a public hanging wasnt a sufficient deterrent after all. Salopian locals loved a public hanging. Whether you resented the accused or secretly sympathised with them and hoped for a reprieve, hangings would often attract thousands of spectators. In fact, some loved a good execution so much that they would ask for the day off work so they could take in a hanging and then go on to do something else afterwards too, to make a real day of it. Unfortunately for those who thrived on the drama, the law evolved and public hangings came to an end. The first private hanging in Shrewsbury occurred after William Samuels was convicted of murder. He was hanged on the 28 July 1886, using the timbers from the old scaffold. The execution was conducted by a Yorkshireman by the name of James Berry, who was picked from over 2,000 other applicants. Berry was eventually to execute 117 people over his career, at 10 per execution (in addition to travel expenses) a modern equivalent of over 1,000.

In addition to hanging, punishment was seen in the forms of stocks, gibbets, imprisonment with hard labour, whipping and transportation. For those accused of witchcraft, burning at the stake was an old favourite, something which proved unfortunate for Mrs Foxall, who was executed in this manner in the Dingle in 1647.

Researching and writing about 365 events has produced quite a mixed bag. Some of the incidents left me appreciating the best in our human nature: for example, when Edward Neville Richards risked his life to save a pony, or when Kenneth Raymond Cooper saved the lives of his workmates at the cost of his own life on a demolition site. Other incidents left me completely despairing of it. There were altogether too many incidents of children dying at the hands of their own parents, an act most of us cant even imagine. For those of you with an interest in crime and misfortune, I hope you enjoy the following stories and all their grisly details.

Samantha Lyon, 2013

Lungs afflicted with tuberculosis.

(Library of Congress, LC-USW3-016047-C)

JANUARY 1939 In the past tuberculosis claimed a great number of lives and destroyed many households. The best chance for a complete recovery involved a stay in an isolation hospital, as general hospitals had a tendency to turn away patients with the notoriously contagious disease. In the early twentieth century the situation was dire in Shropshire, and pulmonary tuberculosis killed over 120 people per year. This meant that it took more lives than all other infectious diseases combined. By 1907 the only institution in Shropshire that would accept patients was the Shirlett Sanatorium, and by 1918 Shirlett was running at full capacity. Until 1931, Shropshire County Council was paying 83 per cent of each patients maintenance costs. Unfortunately, however, even this proved insufficient, and the sanatorium ran up a huge debt. Shirlett was forced to ask the council to increase their contributions by a further 9 per cent. By 1938 the situation hadnt improved, and there were worries that patients would have to be sent away. Thankfully for the patients, however, from the 1 January 1939 the council agreed to pay the extra money, and the sanatorium was able to stay open.

JANUARY 1849 On this day, in Acton Burnell, PC John Micklewright came out the worse for the wear after a fight with local labourer Charles Colley. After a good few drinks in the Stags Head, an inebriated Colley was ready for combat. PC Micklewright was called to deal with this difficult customer. He escorted Colley from the pub and told him to go home. Colley flatly refused, and eventually grew so angry that he actually attacked Micklewright, beating him and breaking his leg. Micklewright was looked after by a local doctor, and was admitted to the Royal Salop Infirmary soon afterwards. Sadly, however, the injured policeman died of his wounds fifteen days later. During court proceedings Colley tried to prove that he did not intend to kill Micklewright, and that he had no idea the man was a policeman. He claimed that his actions were carried out in self defence, and that he therefore lacked the malicious intent necessary for a charge of murder. After only two minutes of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of manslaughter. The judge believed that the jury had been extremely lenient but accordingly Colley was given ten years transportation. To make matters worse, this assault occurred at a time before social security or pensions, and there was no one to provide Micklewrights grieving widow with financial support. She was forced into a workhouse, where she died soon after.

Next page