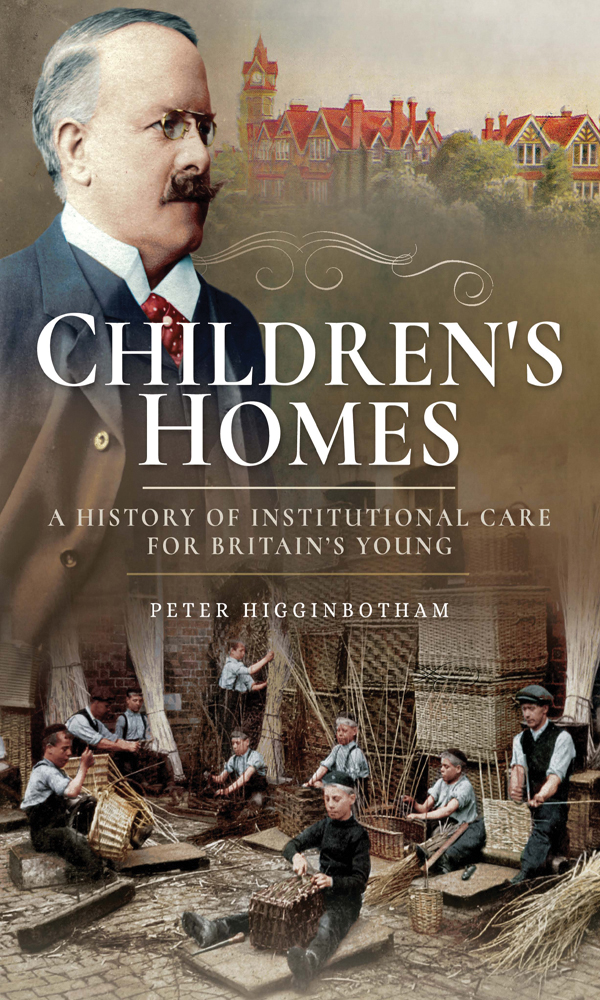

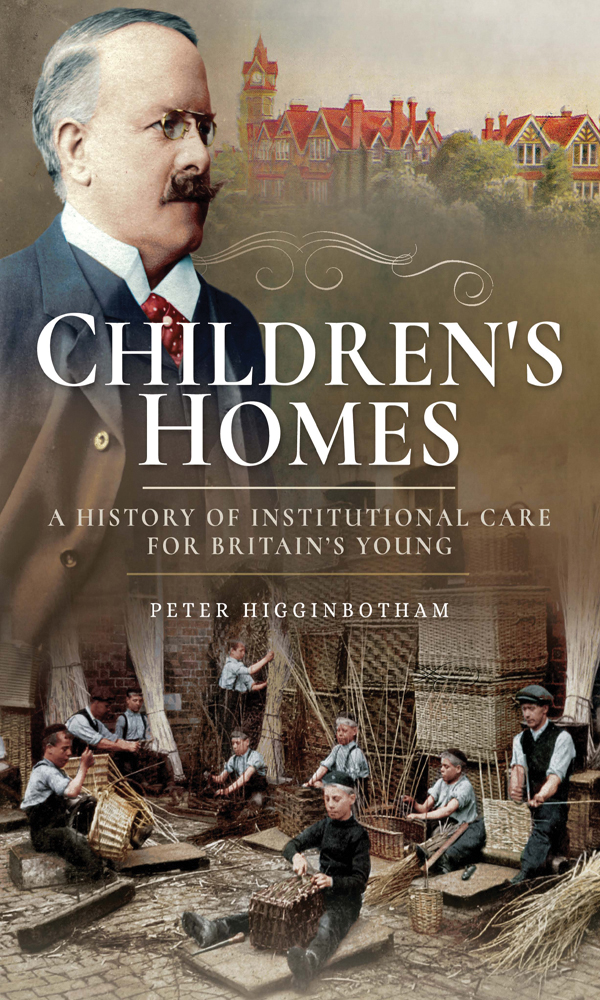

CHILDRENS HOMES

CHILDRENS HOMES

A History of Institutional Care for Britains Young

Peter Higginbotham

For my mother

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Peter Higginbotham, 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 135 0

eISBN 978 1 52670 137 4

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 136 7

The right of Peter Higginbotham to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

What image does the word orphanage conjure up in your mind? A sunny scene of carefree children at play in the grounds of a large ivyclad house? Or a forbidding grey edifice whose cowering inmates are ruled over with a rod of iron by a stern, starched matron? Ever since Victorian times, the promotional and fund-raising literature for childrens homes has, of course, tried to portray them as rather idyllic places where, despite their unfortunate situations, the residents were tenderly nurtured. However, there is now much evidence that some childrens institutions were indeed fearful places where children were, at least by present-day standards, badly treated even if it was often with the best of intentions by those who ran those establishments. Events in more recent times have given us an even grimmer image of childrens homes as places where the residents were sometimes subjected to horrendous physical and sexual abuse by those in whose care they had been placed. So what is the real story? Who founded and ran all these institutions? Who paid for them? Where have they all gone? And what was life like for their inmates?

Over the years, children have needed to find residential care outside their own family for many and diverse reasons. Orphans those whose parents were both dead were perhaps the most obvious group in need of a new home, but children in rather less clear-cut situations could also be included in this category. Children having just one available parent, sometimes referred to as partial orphans, were often treated with the same regard as full orphans, as were those whose parents had abandoned them.

Destitution, by reason of the parents unemployment, illness or other circumstances, was another common cause of a childs needing care to be provided, although this might only be on a temporary basis if the parents situation changed. By the middle of the nineteenth century, there was also increasing concern for children whose parents were considered unfit for the role, or where the home environment was deemed to be detrimental to the childrens welfare.

Although institutional care for disadvantaged children can be traced back to at least Tudor times, it was the latter part of the Introduction eighteenth century that saw the rise of charitably funded asylums for the orphaned or destitute, particularly in London. The number of these gradually increased, with establishments also being founded for the children of soldiers, mariners, police officers, railway workers and other occupations. However, it was not until the last quarter of the nineteenth century that the voluntary provision of institutional care for the young became widely available. Up until that time, for most children in difficult circumstances, it was the workhouse only that had offered an alternative home.

Much of the activity that resulted in this new provision was by groups who believed that children needed to be rescued from bad surroundings and placed in institutional care, where they could be given the education, practical training, discipline and, above all, the religious instruction that would stand them in good stead in their adult lives. The Victorian period also witnessed an expansion of the middle class who provided considerable support for the increasing number of charitable organizations. This included not only direct financial contributions, but also a veritable army of women, often well educated, with the time and resources to assist charities in their administration and fund-raising efforts.

In both the charitable and workhouse sectors, the physical form taken by their childrens provision evolved considerably over the years, gradually moving away from large monolithic orphanage institutions to the much more domestic scale of cottage homes and family group accommodation. For boys with an interest in a seafaring career, a number of training ships were set up.

Concern that children from particular religious communities should not be in danger of losing their faith, particularly when placed in the workhouse environment, led to the setting up of many homes by religious organizations, most notably the Roman Catholic Church. Such groups were also frequently involved in the increasing provision of preventive homes for girls in moral danger, and Penitentiaries or Magdalen Homes for young, unmarried mothers.

Special homes were set up, too, for children with a variety of physical or mental disabilities, and diseases such as tuberculosis, together with convalescent homes for children who were frail or recovering from illness.

In the 1850s, for children who had committed a criminal offence, an alternative to prison became available to the courts in the shape of the Reformatory School. For those discovered sleeping rough, or who were considered in moral danger, or beyond their parents control, the Industrial School an evolution of the Ragged School formalized the process of what we would now refer to as being taken into care. In the 1930s, the Reformatory and Industrial Schools were replaced by Approved Schools, themselves succeeded in the 1970s by Community Homes with Education.

For organizations which took children into care on a permanent basis, there could never be enough places for all those who came their way. To keep the door open to new arrivals, the ongoing disposal of at least some of their existing charges was a constant concern. Two main solutions were adopted for dealing with this problem. The first was boarding out what we now call fostering where children were placed with families who received a weekly payment to cover the costs. The second was emigration, where large numbers of children were sent to begin new lives overseas, with Canada being the main destination until the 1920s when Australia became a more amenable host. Homes were established in Britain to prepare those about to emigrate, and in Canada and Australia to receive new arrivals before they were dispersed to their new families or employers.

After the Second World War, local authorities were given the leading role in the provision of childrens services. At the same time, the focus of childrens care underwent a major shift away from institutional accommodation towards fostering. These developments, together with changing social attitudes towards matters such as single motherhood, led to a steady decline in the demand for residential places in the voluntary sector. By the 1980s, virtually all the homes run by the traditional childrens charities had closed. The central role of local authorities as the front-line provider of childrens services continues to the present day. Increasingly, however, they contract out their residential care provision to the commercial sector.

Next page