The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

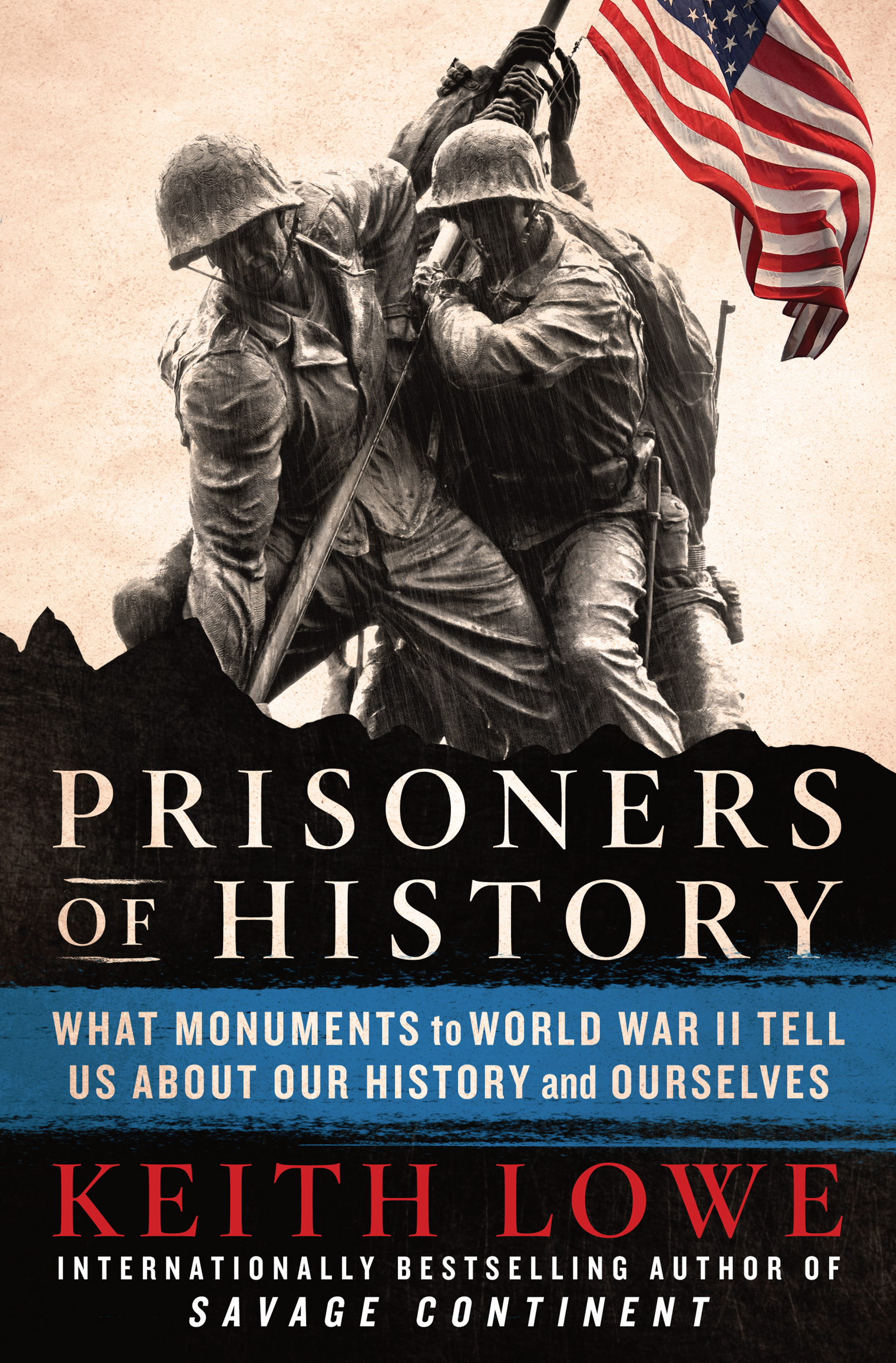

In the summer of 2017, American state legislators began removing statues of Confederate heroes from the streets and squares outside public buildings. Nineteenth-century figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, who had fought for the right to keep black slaves, were no longer considered suitable role models for twenty-first-century Americans. And so they came down. All across America, to a chorus of protest and counter-protest, monument after monument was removed.

There was nothing unique about what happened in America: elsewhere, other monuments were also coming down. In 2015, after the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes from outside the University of Cape Town, there were calls for the elimination of all symbols of colonialism across South Africa. Soon the Rhodes Must Fall campaign spread to other countries around the world, including the UK, Germany and Canada. In the same year, Islamic fundamentalists began destroying hundreds of ancient statues in Syria and Iraq on the grounds that they were idolatrous. Meanwhile, the national governments of Poland and Ukraine announced the wholesale removal of monuments to Communism. A wave of iconoclasm was sweeping the world.

I watched all this happening with great fascination, but also with a certain incredulity. When I was growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, such occurrences would have been unthinkable. Monuments everywhere were regarded merely as street furniture: they were convenient places to meet and hang out, but few people paid them much attention in themselves. Some were statues of forgotten old men, often with strange headgear and improbable moustaches; others were abstract shapes made of concrete or steel; but either way we did not really understand them. There was certainly no point in calling for their removal, because the majority of people did not care enough about them to make any kind of fuss. But in the past few years, objects that were once all but invisible have suddenly become the centre of attention. Something important seems to have changed.

At the same time as tearing down some of our old monuments, we continue to build new ones. In 2003, the toppling of Saddam Husseins statue in central Baghdad became one of the defining images of the Iraq War. But within two years of the statues destruction, a new monument had taken its place: a sculpture of an Iraqi family holding aloft the sun and the moon. For the artists who designed it, the monument represented Iraqs hopes for a new society characterised by peace and freedom hopes that were almost immediately dashed in the face of renewed corruption, extremism and violence.

Similar changes are taking place all over the world. In America, statues of Robert E. Lee are gradually being replaced by monuments to Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King. In South Africa, the statues of Cecil Rhodes have come down, and monuments to Nelson Mandela have gone up. In eastern Europe, statues of Lenin and Marx make way for depictions of Thomas Masaryk, Jzef Pisudski and other nationalist heroes.

Some of our newest monuments are truly vast in scale, especially in parts of Asia. At the end of 2018, for example, India unveiled a brand new statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who was an important figure in the nations independence movement during the 1930s and 1940s. Standing at 182 metres (almost 600 feet), it is now the tallest statue in the world. To create such gigantic structures, at such huge cost, implies an incredible level of self-confidence. These are not temporary structures: they have been designed to last hundreds of years. And yet who is to say that they will fare any better than the statues of Lenin or Rhodes or any of the other figures that once seemed so permanent?

It seems to me that several things are going on here at once. Monuments reflect our values, and every society deceives itself that its values are eternal: it is for this reason that we cast those values in stone and set them upon a pedestal. But when the world changes, our monuments and the values that they represent remain frozen in time. Todays world is changing at an unprecedented pace, and monuments erected decades or even centuries ago no longer represent the values we hold dear.

The debates currently taking place over our monuments are almost always about identity. In the days when the world was dominated by old white men, it made sense to raise statues in their honour; but in todays world of multiculturalism and greater gender equality, it is not surprising that people are beginning to ask questions. Where are all the statues of women? In a country like South Africa, with its majority black population, why should there be so many statues of white Europeans? In the USA, which has a population as diverse as any on the planet, why is there not more diversity on display in its public spaces?

But beneath these debates lies something even more fundamental: we cant seem to make up our minds what role our communal history should play in our lives. On the one hand we see history as the solid foundation upon which our world has been built. We imagine it as a benign force, offering us opportunities to learn from the past and progress to our future. History is the very basis of our identity. But on the other hand we view it as a force that stultifies us, holding us hostage to centuries of outdated tradition. It leads us down the same old paths, to make the same mistakes again and again. When left unchallenged, history can ensnare us. It becomes a trap, from which escape seems impossible.

This is the paradox that lies at the heart of our society. Every generation longs to free itself from the tyranny of history; and yet every generation knows instinctively that without it they are nothing, because history and identity are so intertwined.

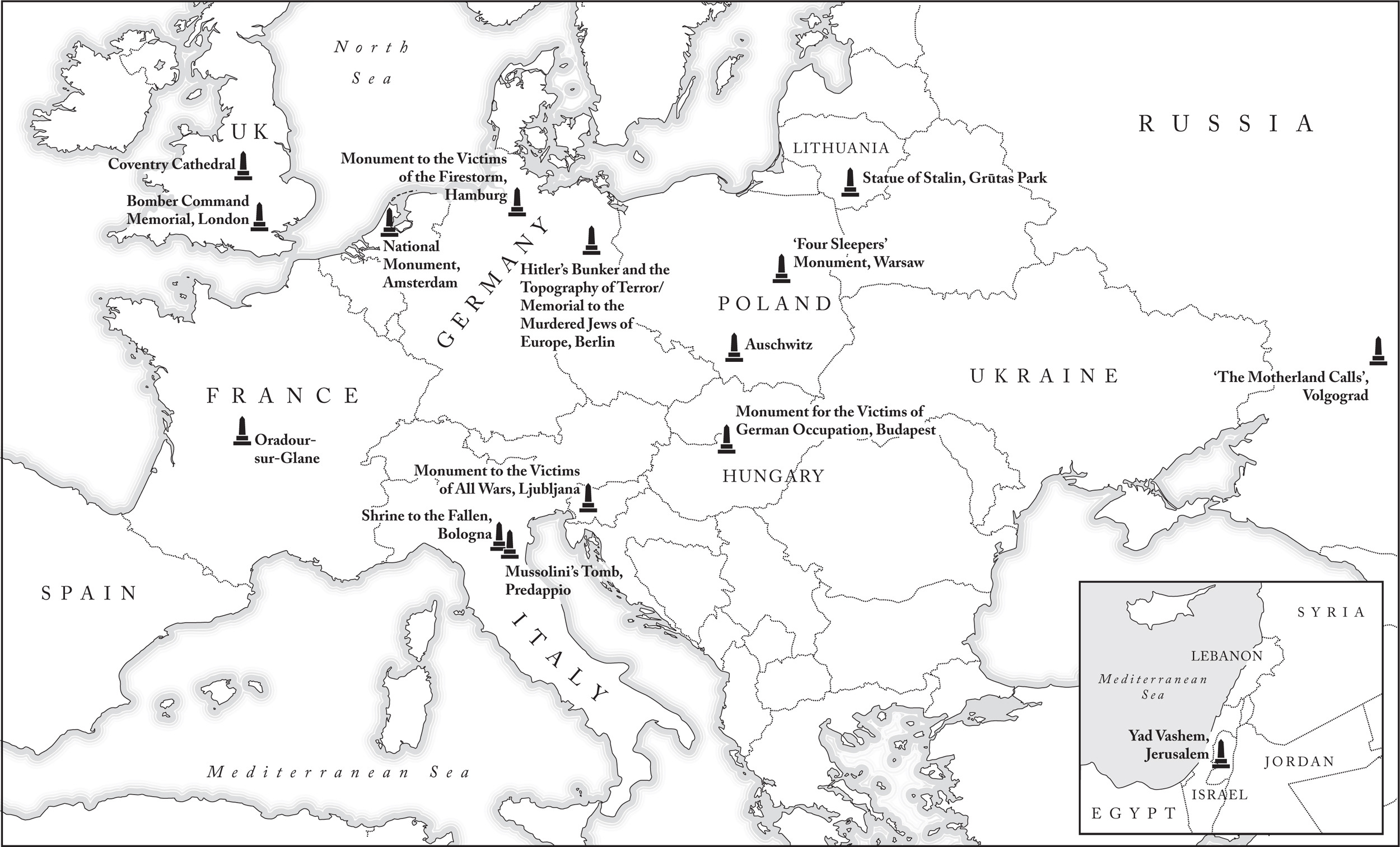

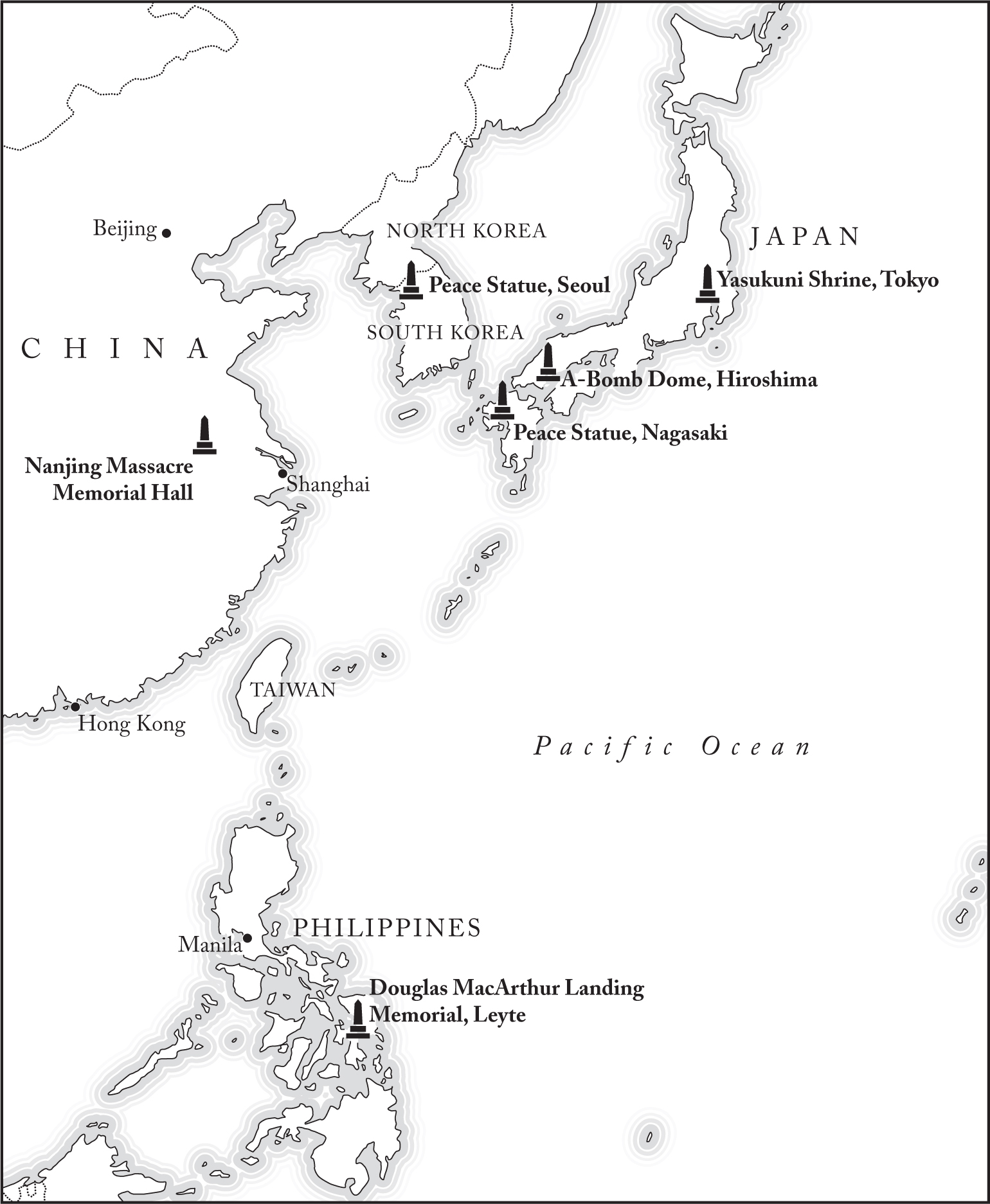

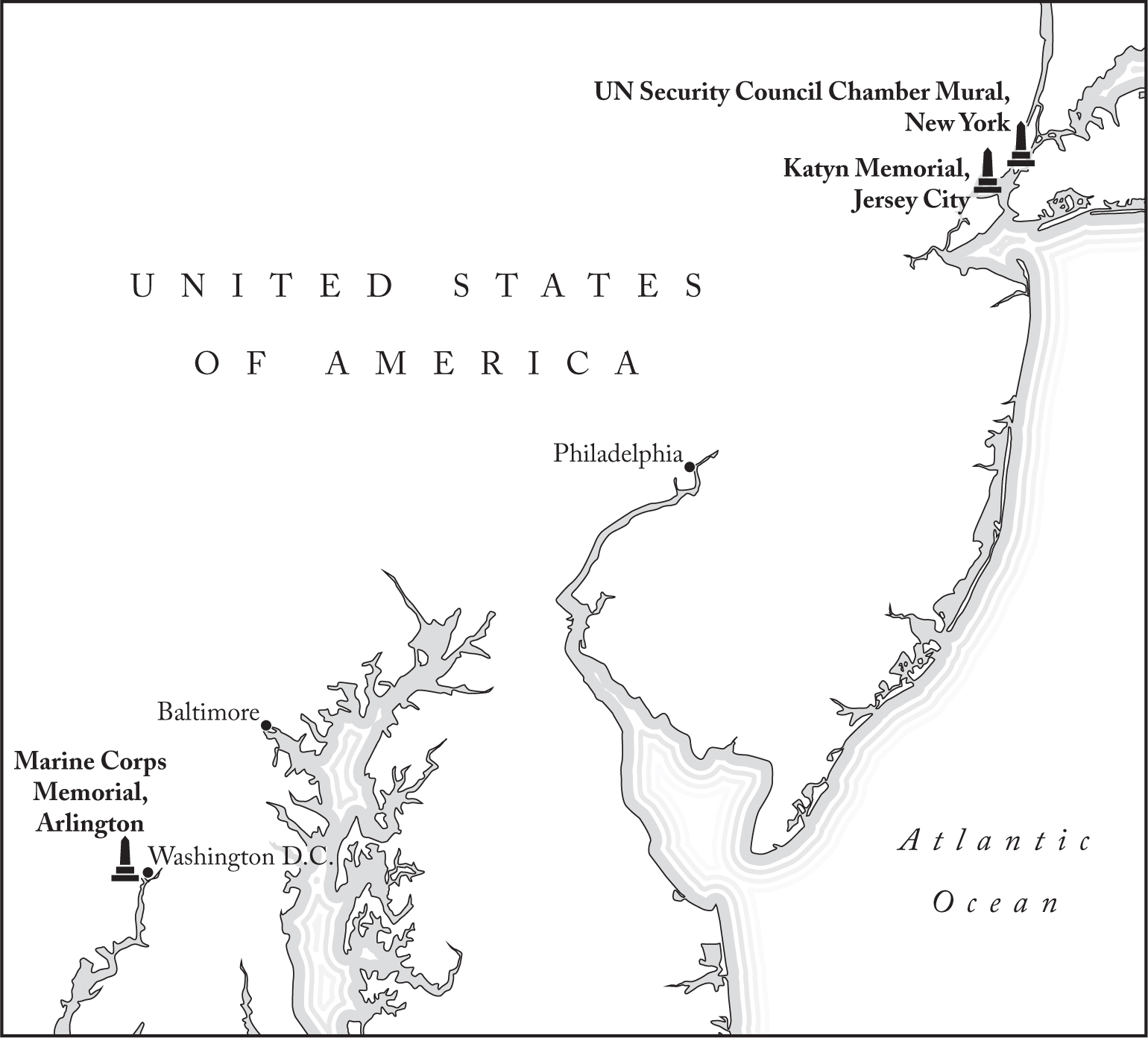

This book is about our monuments, and what they really tell us about our history and identity. I have picked twenty-five memorials from around the world which say something important about the societies that erected them. Some of these memorials are now massive tourist attractions: millions of people visit them every year. Each of them is controversial. Each tells a story. Some deliberately try to hide more than they reveal, but in doing so show us more about ourselves than they ever intended. What I most want to demonstrate is that none of these monuments is really about the past at all: rather, they are an expression of a history that is still alive today, and which continues to govern our lives whether we like it or not.

The monuments I have chosen are all dedicated to one period in our communal past: the Second World War. There are many reasons for this, but the most important is that, of all our memorials, these are the only ones that seem to have bucked the current trend of iconoclasm. In other words, these monuments continue to say something about who we are in a way that so many of our other monuments no longer do.