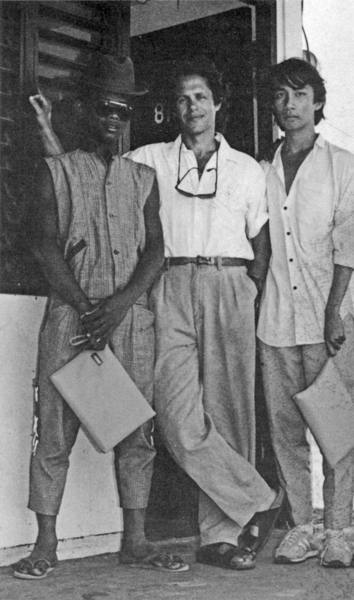

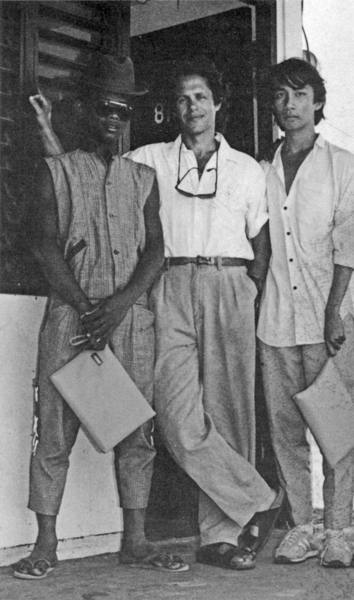

The author between two of his Vietnamese and Amerasian students in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center.

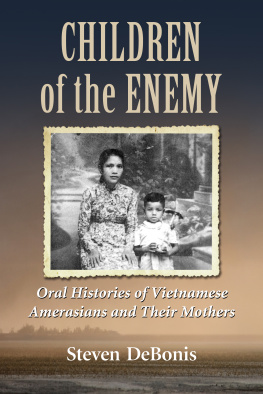

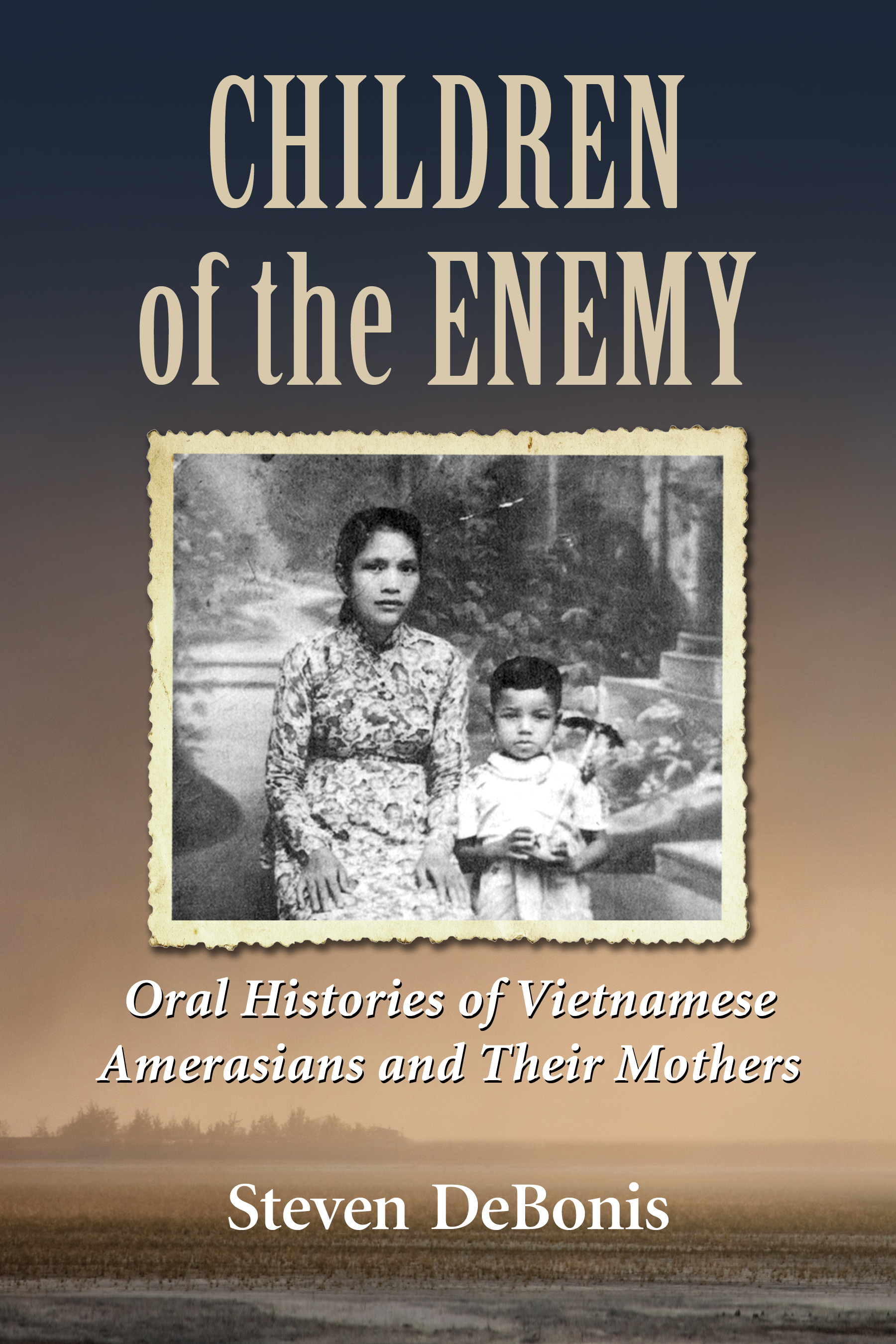

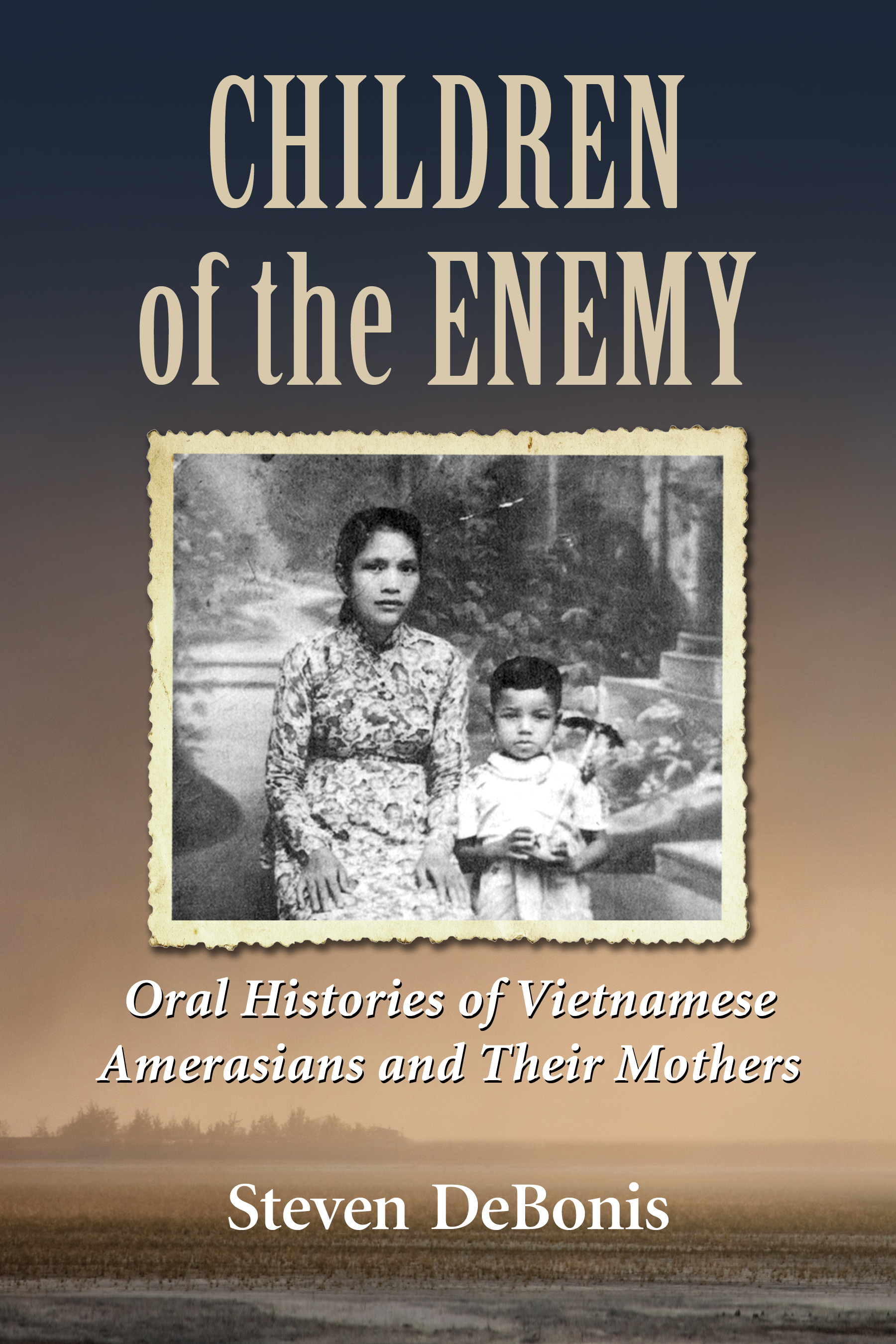

Children of the Enemy

Oral Histories of Vietnamese Amerasians and Their Mothers

STEVEN DEBONIS

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0529-6

1995 Steven DeBonis. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Thuy at five years old with her mother (courtesy Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy); background dust storm (iStockphoto).

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my grandfather, Irving May,

and for my grandmother, Sonia May,

and their great-grandson,

Noah David DeBonis

The guard says, Raymond, whats the song you singing? I say, Im singing my fathers song. He says, Well, you know that if you singin that song, that mean you are the enemy.

Raymond, an Amerasian, describing an

incident in a Vietnamese reeducation camp

She came out of that trance so common to us all and whispered in my ear: Can you describe this? And I said: Yes, I can.

Anna Akhmatova, Requiem

INTRODUCTION

August on the Bataan peninsula is the heaviest month of the monsoon. This is not a rainy season of fair days punctuated by intermittent storms, but one of weeks of drenching rain and terminal humidity. Clouds blow in from off the South China Sea and bump up against the southwestern fringe of the Zambales mountains, where they sit, like overladen ships caught on shoals, loosing their cargo on the land below. The peninsula, brown and thirsty from the remorseless sun of the Philippine summer, turns billiard-table green. Any place mold spores can grab hold and multiply, they do. Leather belts, the suede trim of track shoes, the cloth spines of hardcover books, all mildew to the color of a rice paddy.

Manivong has his most important belonging tucked safely inside his shirt against the August deluge. He carried it this way when he arrived in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC) in Bataan a month ago. From layers of plastic and paper he fishes it out, a five-by-seven photo of a blonde, crew cut American military man wearing a pair of horn-rimmed glasses. Father, he exclaims proudly, pushing the photo across the table to me.

Superimposed over what would be the heart of his dad is a tiny likeness of Manivongs Vietnamese-Khmer mother. On back of the photo is printed a Milwaukee address and inscribed in an almost childlike scrawl:

To Sapim, you are the number one girl of my life. I love you and want you so much.

Love always,

Lt. Ballman (Batman)

I look at the photo and back at Manivong. The likeness is unmistakable. Lt. Ballman was about the same age when the photo was taken as his twenty-year-old son is today.

I have seen scores of such photos in the PRPC, carried by Vietnamese Amerasians fortunate enough to own even that tiny scrap of their past. Many have had the impression that once they get to the United States, waving these snapshots will almost magically cause their fathers to appear. The reality, unfortunately, has been quite different.

Before I came here, I wrote my father sixteen letters from Vietnam, Manivong says. I think someone received them because they were not sent back, but I never got a reply.

In a country where postage for a single overseas letter can eat up an average days wages, sixteen letters represent a substantial investment. Manivong, however, is far from discouraged. He is now using the Red Cross tracing services to try and track down his dad and will continue when he gets to the United States. His chances are not good; only a tiny percentage of the Vietnamese Amerasians who have left Vietnam for America have been successful in finding their fathers.

AMERICAN RESPONSE TO AMERASIANS

The battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 marked the end of the French Colonial Era in Southeast Asia. That same year the French brought 25,000 Franco-Asian children to France and guaranteed them citizenship. The response of the United States to the thousands of halfAmerican children left in Vietnam after its ill-fated venture there has been considerably less immediate.

In 1982, ten years after the majority of U.S. military withdrawal from Vietnam, seven years after the fall of Saigon, Congress passed the Amer-asian Immigration Act. Designed to expedite the immigration of halfAmerican children from a host of Asian countries, it did not affect Amera-sians in Vietnam, as the United States and Vietnam had no relations. Amerasians, however, often with their immediate relatives, did begin leaving Vietnam for the states in September of that year under the auspices of the Orderly Departure Program (ODP).

In light of the horrific plight of the Vietnamese boat people, ODP was created in 1979 to provide a safe, legal alternative to dangerous flight by boat or overland from Vietnam. United States ODP officers from Bangkok travel to Ho Chi Minh City to interview applicants for resettlement in the United States. These applicants have already successfully negotiated the intricate maze of Vietnamese bureaucracy in order to obtain the prerequisite exit permit, often leaving a trail of well-greased palms in their wake.

In 1984, Secretary of State George Shultz, under the prodding of American voluntary agencies, announced the creation of a specific Amer-asian subprogram within the Orderly Departure Program. Still, the rate of Amerasian departures remained slow. In 1986, claiming that the United States had let a backlog of 25,000 applicants build up, Vietnam halted the processing of new Amerasian cases. Amerasian departures from Vietnam dropped from 1,498 in 1985 to 578 in 1986 and to 213 in 1987.

In September of1987, the United States and Vietnam signed an agreement to expedite Amerasian emigration from Vietnam. In December of that year, Congress passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act, also known as the Mrazek Act after its sponsor, U.S. Representative Robert Mrazek. This act, which went into effect on March 21, 1988, allows for Vietnamese Amerasians and specified members of their families to enter the United States as immigrants, while at the same time granting them refugee benefits such as preentry English-as-a-Second-Language training in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center and resettlement assistance in the United States. The cumulative effect of these two events in accelerating Amerasian departures from Vietnam can be seen in the numbers: from 1982 to 1988, ODP brought approximately 11,500 Vietnamese Amerasian children and accompanying relatives out of Vietnam. Extend the period out to December of 1991 and the number jumps to 67,028. Also factored into this increase is the effect of a 1990 amendment to the Homecoming Act which allows both the spouses and mothers (or primary caregivers, including bona fide stepfathers) of Amerasians the right to immigrate with them to the United States. Previously Amerasians had to choose one to the exclusion of the other, a wrenching decision that often tore families apart.

Next page