Table of Contents

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

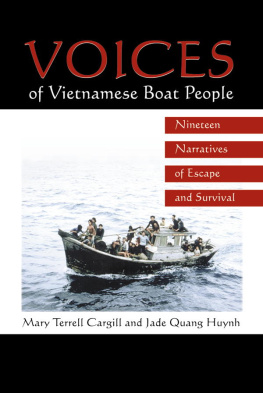

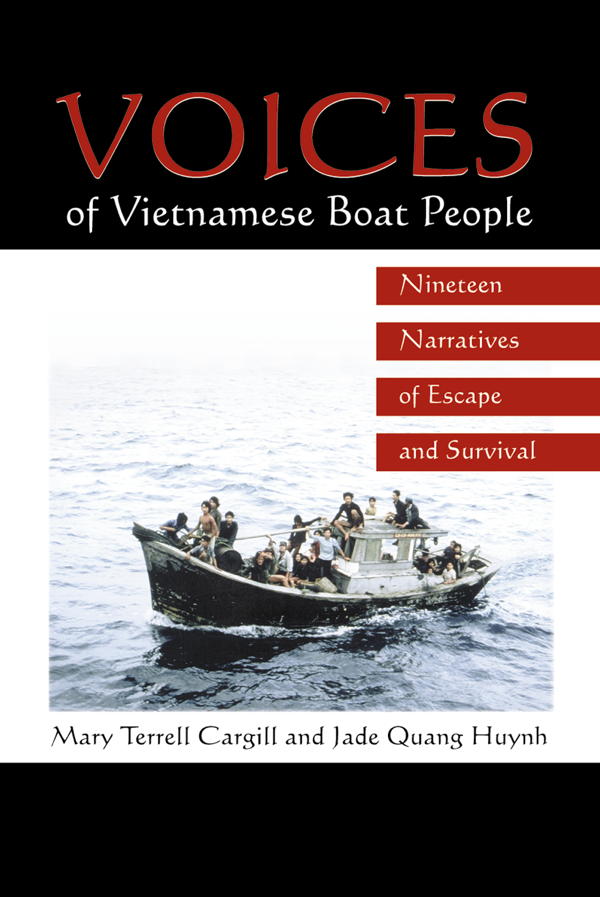

Voices of Vietnamese boat people : nineteen narratives of escape and survival / edited by Mary Terrell Cargill and Jade Quang Huynh.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-0785-9

1. Vietnamese AmericansBiography. 2. RefugeesUnited StatesBiography. 3. RefugeesVietnamBiography. I. Cargill, Mary Terrell, 1945 II. Huynh, Jade Ngoc Quang, 1957

E184.V53 V63 2000

973'.049592'00922dc21

[B] 99-86302

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data are available

2000 Mary Terrell Cargill and Jade Quang Huynh. All rights reserved

Front cover photograph courtesy of UNHCR/B. Boyer

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Mary Wrenetta McCain

for her advice and encouragement

Acknowledgments

The contributions of Gail Spake and Stephen W. F. Berwick are gratefully acknowledged.

Preface

In 1995 in a college sophomore literature class I asked my students to write about their relationship with the natural world. As I walked about the classroom peering over the students shoulders, I found that they made frequent references to the oceans beauty and the memories they had of summer trips to the beach. However, student Duyen Nguyens paragraph was different. In it she described the ocean as terrifyinga place associated with darkness, violence, and separation. I asked Duyen if she would be willing to tell her story to the rest of the class. In moving and vivid terms, she told the rapt students of her nighttime escape from Vietnam by boat. She described her journey, without any family members, to Thailand and the rigors of a refugee camp.

In spring 1996, I had Duyens younger sister Lan in the same course, as well as another Vietnamese student, Ai-Van Do. Toward the end of the course the three of us talked about the possibility of committing their stories of escape and survival to paper. Ai-Van said that she had already planned to write her familys story and asked if I would be willing to edit it. Her question awakened in me the possibility of putting together a collection of Vietnamese survival narratives.

I soon discovered, however, that putting together such a collection would not be easy. When I met with a Memphis Vietnamese leader, he said it would be difficult to complete such a project because he felt that too few refugees had the ability and the confidence to express themselves adequately in written English. He also believed that most Vietnamese Americans would be unwilling to tell their stories because they wanted to put their terrible experiences behind them.

I spoke next with Judy Powell, Memphis Services Coordinator of Refugee Resettlement for Catholic Charities. Judys response to the project was entirely enthusiastic. She thought that significant good could come from recognizing the sufferings and triumphs of the Vietnamese community. With Judys encouragement, I moved ahead with the project and completed the first fourteen narratives.

In spring 1998, I asked Jade Quang Huynh to be my coeditor and to help me finish the collection. Of the nineteen narratives now included, Ai-Van Do, Suzanne Tran, and Jade all wrote their stories. The other sixteen are based on interviews. The last story describes Jades return to what had been Leam Sing Refugee Camp in Chanthabury, Thailand. Jades complete escape and survival story, South Wind Changing, was published in 1994 by Graywolf Press and has received many favorable reviews. I am grateful to Jade for his contributions.

I offer this book as a tribute to the courage and endurance of the Vietnamese boat people.

Mary Terrell Cargill

Christian Brothers University, Memphis

January 2000

Introduction

On April 10, 1975, the Hanoi government of North Vietnam took over the South and immediately pulled down the bamboo curtain. The government implemented a merciless policy against the Southerners. This policy created chaos: family breakups, total loss of means, and executions without trial. Day-to-day living became increasingly difficult and dangerous. In the first of the nineteen narratives included in this volume, Ai-Van Do explains how illiterate doctors from the war zones and the North had replaced the hospitals former doctors. [These new doctors] had neither instructions nor medicine. Ai-Vans parents were so frightened of the authorities, they lived as if they were snails inside their shells and did not dare go anywhere to meet anyone. In his narrative, Hung Truong tells how he became both mother and father to his three younger brothers. When his grandfather offered him money to buy clothes for New Years, he responded with a question: I need new clothes? What for? My life is nothing. I dont have a mom. I dont have a father. I need clothes? What for?

Religious persecution, brainwashing, and total control of speech were hallmarks of the period. Ha Nguyen describes how a policeman who didnt like you might just make up a reason and take you to jail. Once the police thought a lady who lived next door to us knew something about a theft. They beat her even though she was pregnant, and she lost the child. She didnt know anything. Everywhere the concentration camps, known officially as reeducation camps, had been built, and New Economic Zones were established. This brutality was most severe toward intellectuals and people who had been tied to the former Southern government. The result of this policy was the refugee exodus.

Thousands and thousands of rickety boats sailed out of South Vietnams rivers, creeks, and beaches into the South China Sea. On the voyages, the refugees faced starvation, pirates, rapists, and the challenges of nature. On his boat, Hung Truong survived a downpour: The rain was driving real hard. It was like somebody took sticks and beat my face real hard. Ai-Vans father wrote on day five of his sea diary: It was as though we were in a large valley surrounded by many high mountains of water. All of us still think that perhaps we will die here. Hung Lang recounts his actions after being at sea many days without food or water: I wrote a letter, put it in a bottle, and threw it overboard, hoping someone would find it and let my family know that I had died on the sea. No statistics exist on the number of boat people who traveled the waters outside Vietnam or how many died at sea. But no one doubts that the South China Sea became a vast burial ground.

Although the lucky ones who made it to the refugee camps were confronted with an uncertain future, they had a good chance of survival. Minh Nguyens parents learned the ways of survival: You might trade an egg for a cigarette, depending on your need. Lan Nguyen wound up in a Thai camp, where she and her family lived in fear of the guards: If they saw a young girl and they wanted to make her sleep with them, they might beat her if she resisted. However, not all was bleak in the camps. Binh Le watched television for the first time in a Malaysian camp: There were two 20-inch color televisions for about 10,000 people. I loved it.

The nineteen people who tell their stories in this volume all eventually made it to the United States where they had to adapt to a different economic system and become part of an alien society. Like them, thousands of other Vietnamese refugees also had to adjust to a new status in the framework of U.S. society.

Next page