Preface

DURING THE NEARLY four-and-a-half years from July 28, 2014, until November 11, 2018, much of the Western world commemorated the one-hundredth anniversary of World War I. It is noteworthy that most of the official ceremonies marking this centennial were appropriately somber and subdued. There were almost no outward celebrations of heroism, courage, or the eventual victory of the Allied powers, Great Britain, France, Italy, and the United States. This war had simply been too awful, too bloody, and too stupid. It was a catastrophe that never should have happened.

However, while Western Europe and Australia took particular care to remember the war and its dead, the commemorations in the United States were more than a little muted. The government established an official centennial commission in 2013 that planned, developed, and executed various programs, projects, and activities to commemorate the countrys part in the war. However, none of those efforts came close to being as noteworthy as those in Europe, particularly in Great Britain, where the painful losses from the war are still keenly felt. In the United States, one could arguably state that World War I has become something of a forgotten conflict.

Even for those Americans who do remember the war, their mental image of it is limited to rousing songs like George M. Cohans Over There and scenes from grainy films showing smiling doughboys boarding ships bound for France. They do not see, however, the mud, rats, and body lice of the trenches, the dead men laying hideously prone across tangledbarbed wire, nor the thousands forever damaged mentally and emotionally by what people referred to as shell shock.

This lack of knowledge and understanding is tragic given that almost five million Americans served in the war, and the nation suffered over four hundred thousand killed, wounded, and missing during barely a year of combat operations. This conflict was Americas first entry into a major foreign war and the first that demanded a massive, nationwide mobilization. Moreover, a crucial part of that mobilization included something new: the activation of state National Guard units into federal service and their incorporation into the US Army. To be sure, militia-type military organizations and their citizen-soldiers had always played a prominent role in providing American military manpower. However, before the Militia Act of 1903 and the National Defense Act of 1916, there was no formal relationship between state militia organizations like the National Guard and the Regular Army. By the time war was declared on Germany in April 1917, that had changed and, as a result, the lives of millions of men who had enlisted in their local National Guard units in peacetime would be altered forever.

In April 1917, no one had ever seriously considered the idea of sending the US Army across the ocean to fight a war against a major European power. Now, suddenly, the nation needed men to do just that. The Regular Army was very small at the time and, therefore, the only organization capable of providing an immediate source of manpower was the National Guard. They were not ready for a war of any kind, and neither they nor their Regular Army counterparts were prepared to fight the kind of war that had been raging on the Western Front in France since the summer of 1914.

In June 1917, just a few months after war was declared, the first division of Regular Army infantrymen left for France. Initially, that was the best America could do. The next men to deploy overseas would have to be from the National Guard. The War Department and its Militia Bureau determined which National Guard units had the highest state of readiness, as low as that state might actually be. The first National Guard division to go to France was the 26th Division, which was formed from units in the New England states. Next, the War Department decided to mobilize the remaining National Guard units deemed ready into a single organization, the 42nd Division, and sent them to France only a few weeks after the departure of the 26th Division. Because this new division had National Guard units from twenty-six different states and stretched acrossthe nation like a rainbow, it became known as the Rainbow Division. It would be one of the most famous American military units to fight in World War I.

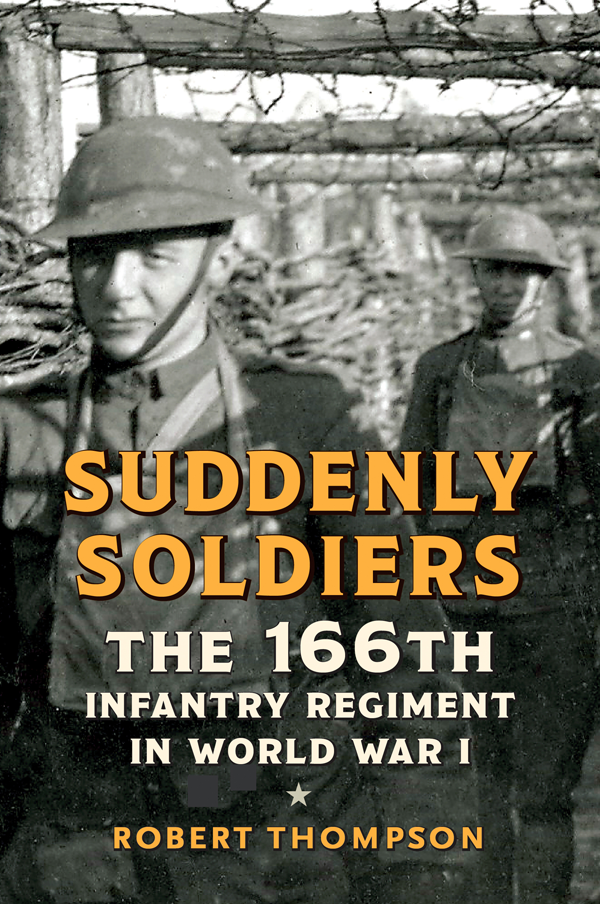

One of the National Guard units picked by the War Department for the Rainbow Division was the 4th Ohio Infantry Regiment, which they redesignated as the 166th Infantry Regiment of the US Army. The companies that made up the regiment came from ten towns across Ohio, and the men who went to fight were very ordinary, the sort of people all of us know even today, who do everyday jobs and live unremarkable lives. But now, they would be asked to do something so extraordinary that they would have never considered it in their wildest dreams, or perhaps, one should say, their worst nightmares. That is what I found so compelling about their story, and that is why I decided to write it down for everyone to read.

In collecting source material, I was greatly aided by two previous histories written about the 166th. The first was Ohio in the Rainbow: Official Story of the 166th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Division, in the World War, which was written in 1924 by a former captain in the regiment, Raymond Cheseldine. The second history was authored by another officer from the regiment, Alison Reppy, in 1919 and was titled Rainbow Memories: Character Sketches and History of the First Battalion, 166th Infantry, 42nd Division, American Expeditionary Force. Both offered excellent starting points for my research, providing a wealth of material and an excellent chronological basis for the regiments story. But, at the same time, they both suffered from one understandable failing.

Written shortly after the war for an audience that was made up primarily of the regiments veterans and their families, both books tended to take a somewhat romantic approach to the war, deemphasizing the pain, suffering, and loss experienced by the men of the regiment. That shortcoming left me needing sources that were more intimate, grittier, and a bit more honest and forthright.

Luckily, I was able to find those sources in the form of journals, diaries, and letters from soldiers in the 166th, and they were critical in producing the final product. Some of these were published, but most were not. Most of the unpublished documents were made available online by descendants of the soldiers who wrote them. Meanwhile, others could be found in the archives of the Ohio Historical Society, now known as the Ohio History Connection. The information in these documents helped tell the soldiers real stories, providing not just personal details but also color and texture.Also, they helped fill blanks in the official versions of the regiments history, as well as provide essential information missing in the other two books, as well as important clarifications of some issues.