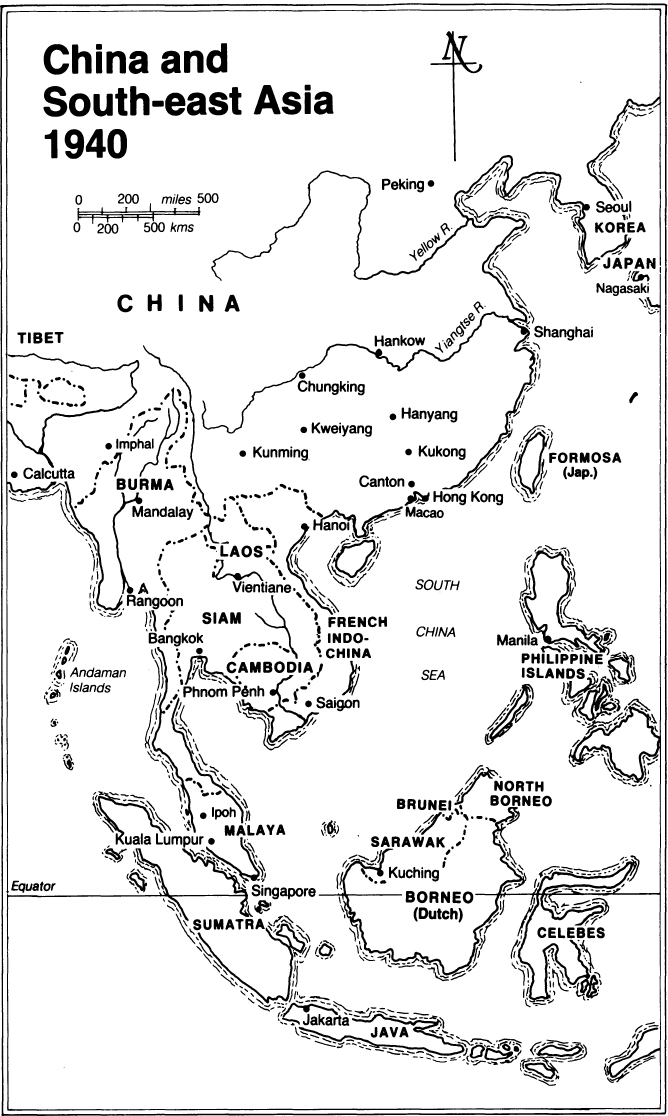

(See )

At dawn on the morning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor I went up on to the deck of the Tai Shan, the largest of the Hong KongMacaoCanton river steamers, and joined Captain Muir on the bridge as we entered Hong Kong harbour. It was in fact a few hours after Pearl Harbor had been bombed and, because of the date line, was Monday, 8 December. The harbour, which was the fourth busiest in the world, was empty and Captain Muir told me that everything that could get up steam had left the day before and that the volunteers had been mobilized. While we were talking we heard the drone of aircraft and the first Japanese bombs began to fall on Hong Kong. Having originally prepared for an air war against Germany, I was about to become involved in a ground war against Japan.

While at Cambridge University I had joined the University Air Squadron and in 1936 had been commissioned in the Reserve of Air Force Officers. Many hours were spent in the air learning the geography of southern England where most of us expected the major battles of the air war with Germany to be fought. I had been tempted to apply for a regular RAF commission with eighteen months seniority for my honours degree in history but stuck to my earlier intention, formed while at school at Marlborough, of joining the Colonial Service. I was selected for the Malayan Civil Service and was sent on a years Colonial Service course at Oxford University. On arrival in Malaya in 1938 I was initially stationed in Ipoh, the centre of the tin mining industry, before being sent to Macao, a small Portuguese colony forty miles south of Hong Kong in the Pearl River estuary, to learn Chinese (Cantonese). Here I rejoined Ronnie Holmes and Eddie Teesdale, two Hong Kong cadets, who had earlier come out with me on the P&O ss Carthage from England.

On the outbreak of war with Germany I was called up to the RAF in Singapore but in early 1940, after a few months of the phoney war, was demobilized again at the request of the Malayan Government and returned to Macao. On the way back by ship I passed through Saigon, then a peaceful French town, which I was to see again twenty years later in very different circumstances. On the fall of France in 1940 it was considered safer to move all the Colonial Service cadets learning Chinese to Hong Kong.

Hong Kongs defences against a Japanese attack were being steadily improved and I was invited to join a group, with Ronnie and Eddie, which was to operate as a left-behind party in the New Territories if and when the Japanese advanced. We spent most weekends exploring the hills of the New Territories and learning the tracks. During the week I used to fly members of the party over the same ground in an old Hornet Moth belonging to the Hong Kong Flying Club at Kai Tak, then a grassy circular field roughly where the airport buildings and apron are now. We naturally concentrated our attention on the hills covering the likely route of a Japanese advance from the border to Tai Po, thence to Sha Tin and Shing Mun reservoir, where the government bungalow was allocated to us and became our training HQ. Dumps of supplies (food, ammunition and explosives) were laid for us by the Kumaon Rifles. The whole area of each dump was first cleared of Chinese woodcutters and the supplies were brought in by mules. The most important (No. 2) was built into a cave under rocks in a stream bed in the valley between Shing Mun reservoir and the crest of Tai Mo Shan. Another (No. 4) was in a disused shaft of the wolfram mine at Lin Ma Hang, looking right down on the border with China.

The leader of the left-behind party was a great character, Mike Kendall, a stocky Canadian mining engineer, which made him an expert with explosive and in 1941 some of the new gadgetry from the UK arrived including limpet mines, time-pencils and all sorts of booby traps. Major-General A. E. Grasett, himself a Canadian, then commanding Hong Kong, invited Mike and myself to a demonstration. When we arrived in shirt and shorts he was standing on a small mound surrounded by a Yes of smart staff officers. He greeted Mike.

Ah, Kendall, just the chap we need to go up close to these things and see what theyre like when they go off.

Without pausing for breath Mike came straight back, Well, sir, I wouldnt mind if I had a skin as thick as yours. The faces of the staff officers were a treat, but the General gracefully accepted such a riposte from a fellow Canadian.

All the time we watched the Japanese across the border, notably where it ran down the centre of the main street of Sha Tau Kok. Here British and Japanese troops were literally face to face. Locally it was quite impossible to tell when the invasion might come as everything had been ready for months. Unless there was warning from elsewhere it was bound to be a surprise. For some unfathomable reason at the beginning of November, 1941, the Malayan Government allowed the Malayan cadets to return to Macao. This suited me as I was within two months of taking my final Cantonese examination and needed a concentrated finish. On Sunday afternoon, 7 December, while skeet-shooting on Macao racecourse, the Consul brought me a message from Mike to get back to Hong Kong immediately. There was no rush as the