The Malayan Emergency

and

Indonesian Confrontation

The Malayan Emergency

and

Indonesian Confrontation

The Commonwealths Wars 19481966

Robert Jackson

First published in Great Britain in 1991 by Routledge

Printed in 2008

Reprinted in this format in 2011 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Robert Jackson 1991, 2008, 2011

ISBN 978 1 84884 555 8

The right of Robert Jackson to be identified as author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission

from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

By CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

Between 1948 and 1966, British and Commonwealth forces fought two campaigns in South-East Asia, the first against Communist terrorists in Malaya, the second against Indonesian forces in Borneo. Both campaigns were concluded successfully, and had far-reaching consequences for the political stability of the Eastern Hemisphere.

The political background to both campaigns is complex and largely outside the scope of this work, which attempts to set out the military achievement in as concise a manner as possible, and to examine the lessons that were learned from it. A great many military units were involved in prosecuting both campaigns, and although some have been singled out for special mention it has been impossible to deal fairly with the achievements of them all, particularly in the context of the Malayan Emergency. A full list of military and air units involved will be found in the appendices to this book, together with a bibliography of recommended further reading.

RJ

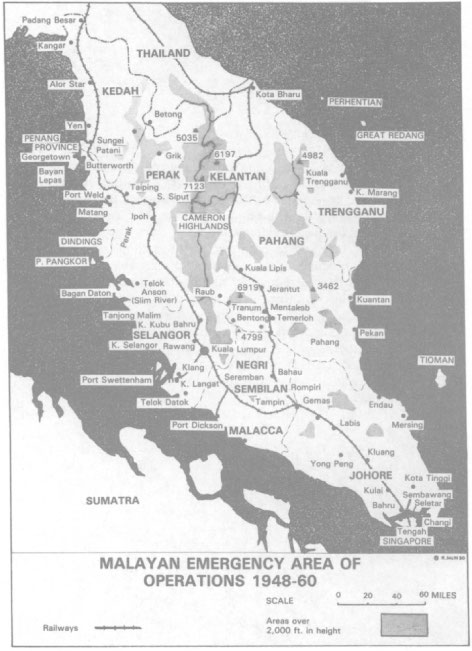

Malaya is one of the most beautiful, and at the same time one of the most primordial, countries on earth. In the north, the narrow Kra isthmus binds it to Thailand, its only land frontier; the peninsula itself is some 500 miles long, a little larger than England without Wales, ending at the Johore Strait which separates it from the island of Singapore. To the east, the South China Sea stretches away to the Philippines and the Pacific; to the west, beyond neighbouring Indonesia, lies the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean.

The hinterland of Malaya more correctly known nowadays as Peninsular Malaysia is largely inaccessible. The central mountain ranges, running like a spine along much of the countrys length, rise to 7,000 feet at their maximum elevation. On their western, steepest side, rivers plunge down the mountain slopes in waterfalls and fast-flowing streams until they reach the 50-mile-wide coastal plain which faces Sumatra across the Malaccan Strait; on the eastern flank the slopes are gentler and the rivers longer and lazier, flowing into the South China Sea over palm-fringed beaches.

Carpeting the mountain ranges is the dense jungle, one of the oldest rain forests in the world. One hundred million years old, it covers four-fifths of the peninsula, together with its associated mangrove swamps:

Harsh and elemental, implacable to all who dare to trifle with its suffocating heat or hissing rains, the jungle alone has remained untamed and unchanged . Here the tall trees with their barks of a dozen hues, ranging from marble white to scaly greens and reds, thrust their way up to a hundred feet or even double that height, straight as symmetrical cathedral pillars, until they find the sun and burst into a green carpet far, far above; trees covered with tortuous vines and creepers, some hanging like the crazy rigging of a wrecked schooner, some born in the fork of a tree, branching out in great tufts of fat green leaves or flowers; others twisting and curling round the massive trunks, throwing out arms like clothes-lines from tree to tree. In places the jungle stretches for miles at sea level and then it often degenerates into marsh, into thick mangrove swamp that can suck a man out of sight in a matter of minutes .

In an evergreen world of its own that will never know the stripped black branches of winter, elephants, tigers, bears and deer roam the thick undergrowth; flying foxes, monkeys and parrots chatter and screech in its high places; crocodiles lie motionless in the swamp; a hundred and thirty varieties of snake slither across the dead leaves on wet ground; the air is alive with the hum of mosquitoes ferocious enough to bite through most clothing; and on the saplings and ferns struggling to burst out of the undergrowth thousands of fat, black, bloodsucking leeches wait patiently for human beings to brush against them. Only on the jungle fringe is there colour and light and a beauty unmarred by fear. Here, when the sun comes out after a tropical shower, thousands of butterflies hang across the heat-hazed paths in iridescent curtains. Brightly coloured tropical birds dart like jewels between clumps of bamboo, giant ferns, ground orchids, flame of the forest trees, bougainvillaea, wild hibiscus, in a countryside heavy with the scent of waxen-like frangipani blossoms, where the occasional monkey watches suspiciously from the heights of a tulip tree with its clusters of poppy-red flowers.

(Noel Barber, The War of the Running Dogs)

This description of the Malayan jungle, by a man with first-hand experience of it over many years, is one of the best there is. It summarizes the contrasts of the wild, natural landscape that dominates every aspect of Malayan life. In its depths live the aboriginal tribespeople, shy folk who hunt small game with their blowpipes and who live in communal houses built on piles driven into the edge of a river near the plots of land where they cultivate their simple crops of rice, vegetables and sugar cane. Here, in their kampongs on the jungle fringes, close to the sea or the rivers, live the Mohammedan Malays, the indigenous people of the land, an attractive, courteous and endearing race who live their lives at a leisurely pace; they grow rice, breadfruit and papayas in and around their villages, harvest ginger, cinnamon and figs from the countrysides natural bounty, fish the abundant rivers and derive oil, roofing materials and coconuts from the palm groves.

The way of life of the Malays contrasts sharply with that of the Chinese. They are the town dwellers, and their lives revolve around commerce, although their influence has declined over the past forty years. In Singapore their influence is strong, but on the mainland, mainly because of the events described in this book, they have been ousted from posts of importance. Nevertheless, together with the Indian population of Malaysia, they continue to be a vibrant force in Malaysias economic climate.