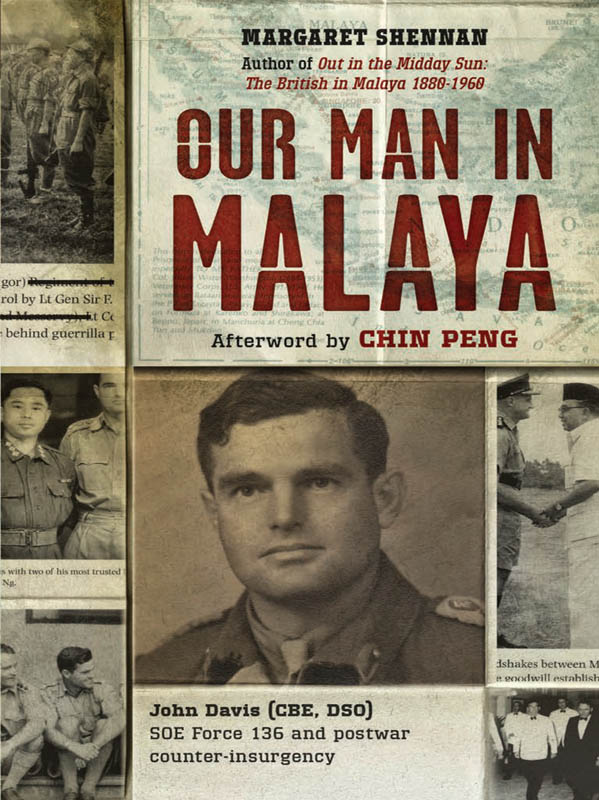

Our Man in Malaya

J OHN D AVIS CBE, DSO,

SOE F ORCE 136

AND P OSTWAR C OUNTER- I NSURGENCY

Margaret Shennan

Contents

Dedication

For Helen,

Patta, Bill, Humphrey and Tom,

to whom this story now belongs

Acknowledgements

The career of John Davis was inextricably and paradoxically intertwined with that of Chin Peng, the leader of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). For more than fifty years their mutual respect overcame their ideological differences.

I am deeply grateful to Chin Peng for his contribution to this biography of his friend and adversary.

* * *

Serendipity plays a large part in the evolution of this book. In 1999, while writing Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya, 18801960, I was struck by the wartime heroics of a police officer called John Davis. After a mutual acquaintance gave me his telephone number, I was able to question John Davis further about his wartime experiences. I did not know then that in 19546 he was Senior District Officer (SDO) in Butterworth, Province Wellesley, which was home to me during eight of my childhood years.

Meanwhile, pursuing information about one of John Daviss closest friends, the late Guy Madoc, I made contact with Madocs daughter, Fenella, who, I then learned, was married to John Daviss nephew also John Davis. After establishing these fortuitous connections, we Fenella, John, my husband, Joe, and I met up in London. The outcome was a tempting invitation to write a biography of John Davis, focusing on his years in the Far East. In the spring of 2000 we met John Davis himself and his wife at their home, together with members of their family. I was assured of their complete cooperation and was given carte blanche to use the Davis private archive, a priceless, eclectic collection of papers that formed the basis of my research and enabled the authentic voice of John Davis to echo down the years.

My gratitude to the Davis family for this opportunity is immense. I thank them for their frankness, cooperation, enthusiasm and hospitality. Talking to John and Helen at length during many visits was enlightening and a great deal of fun. Conversations with their daughter Patta and their son Humphrey invariably produced fascinating insights, such as Humphreys revelations about Kim Philby and his account of the last meeting between John Davis and Chin Peng, at which he and his wife Dilla had been present. My warmest thanks go also to John and Fenella for setting everything in motion, and for their patience and sustained interest in the project.

I thank Professor John Broome and Mr Nicholas Broome for allowing me to make full use of Richard Broomes A Memoir (Wartime Experiences), their fathers detailed record of 1942. I am much indebted to John Loch MCS and Michael McConville MCS for their information and advice, including their personal insights and constructive comments on the manuscript; similarly my sincere thanks to Anthony Short, the leading British authority on the Emergency, for reading the manuscript and for giving me the benefit of his extensive knowledge of the period. Lastly I am extremely grateful to Mr Ian Ward, Media Masters Publishers, Singapore, and Mr Wah-Piow Tan, who have facilitated communications with Chin Peng.

Many others have talked to me about John Davis or helped me with particular matters. My thanks go to Stephen Alexander, Terry Barringer, Helen Bruce, Laura Clouting (Imperial War Museum), A. Cradock, Maurice Dunman (The National Archives, Kew), John Edington, Mary Elder, Peter Elphick, P.W. Giles, Vanessa Harrison (BBC Radio 4), John Hembry, Lynn Keeping, J.S.A. Lewis, Mrs B. Matthews (school librarian, Tonbridge School), Maj Alex Mineef, the Revd Geoffrey S. Mowat, Dr Philip Murphy, Rowland Oakeley MCS, Judy OFlyrin, Penny Prior (Foreign and Commonwealth Office), Professor Jeffrey Richards, the late Harvey Ryves, Brian Stewart MCS, Hubert Strathairn, Roderick Suddaby (Imperial War Museum), Nicholas Webb (archivist, Barclays Group), Joan Welburn and the late Professor Oliver Wolters.

Finally, I thank my husband Joe for his advice as a fellow historian and for his unstinting support, even while he was busy writing another book.

Margaret Shennan

Prologue

On the evening of 24 May 1943 a long, dark, low shape appeared on the horizon some 10 miles to the north of the Malayan island of Pulau Pangkor. An astute observer might have identified the hull of a submarine that was surfacing for a specific purpose in the Malacca Straits. Aboard Submarine 024 five Chinese secret agents waited expectantly as a stocky British Army officer resolutely surveyed the stars and the rise and fall of the land to the north of the headland of the Haunted Hill, Tanjong Hantu. Capt John Davis was leading the first special operations landing on the Malayan Peninsula since the surrender of Singapore to the Japanese fifteen months before.

This new initiative would be a significant enterprise, carried out under the agency of the Special Operations Executives (SOEs) Malaya Country Section, and a great deal rested on its reconnaissance and intelligence-gathering success. If all went well, and communications were restored between Ceylon and Malaya, the present operation, code-named Gustavus I, would be the prelude to a series of sorties to put Chinese agents into Japanese-occupied Malaya. Select parties of volunteers, specially trained in the skills of sabotage, intelligence gathering and guerrilla warfare, would be infiltrated under the command of European officers. In addition, Capt Davis had two further objectives: to discover the fate of a number of Europeans who had volunteered for behind-the-lines operations during the ten-week Malayan campaign and might still be surviving in the jungle; and, last but not least, to make contact with the Chinese Communist guerrillas in Perak, led by a remarkable youth whose wartime alias was Chin Peng, and harness their anti-Japanese zeal to the Allied cause. In implementing the last aim Davis was drawn into political relationships that would profoundly affect his career. The wartime comradeship he was to forge with Chin Peng in life-threatening circumstances during the next two and a half years would be replaced, within a similar time span, by mortal conflict and finally, in old age, by a kind of reconciliation.

As he stared towards the Malayan coast on that May evening Capt Davis, formerly an officer of the Federated Malay States Police Service, was all too aware of his responsibility for making the right operational decisions. Time and again he had rehearsed the outline of the Segari Hills from an old pilots book until he knew it by heart. But there was no knowing what might be waiting there, and suddenly the implications of a blind landing struck home. He and his handful of Chinese volunteers would be alone, facing the unknown; so it would require all the luck in the world to paddle several miles in flimsy, collapsible canoes known as folboats, beach them at the correct point and find cover before entering the dark hinterland unobserved. And luck threatened to desert them when one of the folboats was slightly crushed while being fed through the torpedo-loading hatch. Though this was a not uncommon problem, it was frustrating to a hard-pressed team. Capt Davis was relieved and grateful to the Dutch submarine crew who worked on deck in the dark to repair the damage.

As the little team of SOE men prepared to leave the submarine under cover of darkness, the Dutch skipper, Lt Cdr W.J. de Vries, caught a flash of apprehension on Daviss face. He felt compelled to intervene. Exercising his due authority as commander, he offered the British officer his unequivocal support if he decided that the risks were too great and that, for the sake of his men as well as himself, they should call off the operation. Look. Come back with me, therell be no loss of face, he assured his fellow officer. The gesture was sufficient to revive Capt Daviss morale. He felt a tremendous determination to go ahead with the thing, also a tremendous feeling of gratitude to his Allied colleague for taking that point of view. Davis nodded: the die was cast.